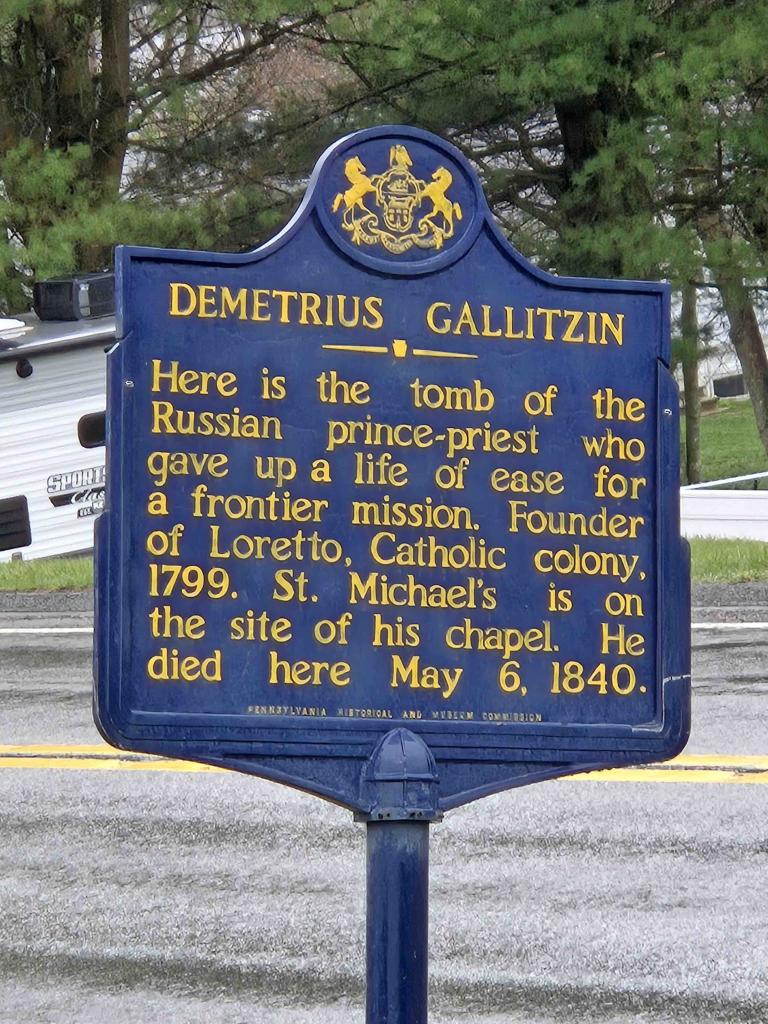

Last time, I wrote about Prince Demetrius Gallitzin, a Catholic priest of Russian origin, who evangelized the western frontiers of Pennsylvania in the early nineteenth century. As I suggested, he might soon become a saint of the Catholic church, and it would be wonderful if that aroused so much interest as to provoke new waves of shrines and pilgrimage trails.

Photograph is my own work

This actually got me thinking about the sacred landscapes around us, including many places that are of very local appeal, and which are often declining in popular interest. But this is a dynamic process, as such places rise and fall, come and go. As I have discussed at this site, European countries just in the past the past two decades have created or restored dozens of great pilgrim routes, which have become immensely popular despite (or because of) surging secularization. Why should the US be different?

Just what the spiritual content of those pilgrimages might be is open to debate, and the line separating faith from tourism is often thin. But was that not always the case? That point certainly applies to Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales.

In fact, clusters of shrines and pilgrimage centers feature on many American maps. Philadelphia has plenty, and Pittsburgh has a standard and quite popular group of five older ethnic churches, the exact contents of which can be adjusted at will. Pro tip: do include St Nicholas church in Millvale, the setting for some off-the-charts astonishing murals by artist Maxo Vanka, which present the Christian story in contemporary terms as viewed through the eyes of a radical far Left Modernist: expect gas masks and barbed wire. (See the sample here).

But let me venture outside the big city, to the small towns and fading industrial communities, and the sometimes spectacular churches they built a century or to ago as symbols of faith, and of community pride. In light of the Gallitzin story, it’s intriguing to think of the whole sacred landscape that we can find in Western Pennsylvania, if we look a little. I here propose the Western Pennsylvania Pilgrimage Route. If we were in modern Europe, including the former diehard heartlands of Protestantism, we would undoubtedly call it the Prince Gallitzin Trail.

Ideally, such a trail would be a hiking venture, mainly using reused rail routes, but you can also see a huge amount as a driving tour, as a series of road trips. The more you travel these routes, the more you fill them in with extra places not even contemplated here.

In the Prince’s Footsteps

But to return to Gallitzin, the future (we hope) Saint Demetrius. Let me divide his “Trail” in two convenient free-standing sections, the first in the Western portions of Pennsylvania, the second in the south-central region, on the Maryland line.

As I mentioned, his primary base was Loretto, which was, I repeat, for several years, the only actual Catholic church between Lancaster PA and St Louis. In that general western PA area, mainly in Cambria County, the Prince survives in placenames, but Loretto itself is an astonishingly rich area, with its minor basilica of St Michael the Archangel, not to mention St Francis’s University. Among many other features, the Marian Grotto here is lovely. You can see the Prince’s crypt.

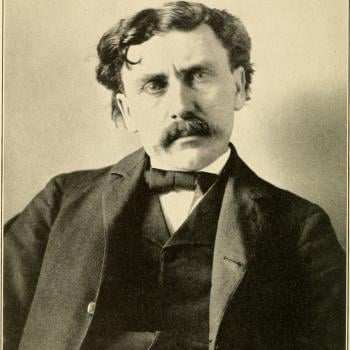

I should explain where the money came from for some of the amazing and often really ornate churches and other buildings that litter this area. In the late nineteenth century, Pittsburgh was extremely prosperous, and its steel and financial magnates liked to spend time in the pleasantly rural Alleghenies. One key figure was Charles M. Schwab, a protégé of Andrew Carnegie, whose family had moved to Loretto when he was in his teens, and who attended St. Francis. He became the first President of US Steel, and a founder of Bethlehem Steel. In his day, he was one of the most powerful men in the American economy, but he was also a playboy, and he died broke. If Prince Gallitzin is a character out of Dostoevsky, then Schwab was taken straight from The Great Gatsby, or maybe Theodore Dreiser. (He was no relation to the founder of the modern Charles Schwab corporation).

Schwab the steelmaster was a philanthropist, and Penn State still boasts its Schwab Auditorium. He poured money into his retreat (mansion) in Loretto, which eventually passed to the Franciscans of St Francis University.The friary is still there, and the grounds include beautiful gardens, and yet another shrine.

Wherever you go in this area, you often see the Schwab name as the patron of churches, buildings and memorials. In Loretto, that included the basilica, and the Gallitzin statue.

It is 25 miles from Loretto to Johnstown, which has a number of notable Catholic churches and sites including St. John Gualbert, which is the “co-cathedral” of the Diocese of Altoona-Johnstown (Charles Schwab was responsible for the organ). You can also see the shrine of Our Lady of Mariapocs, with an icon of special sanctity for Carpatho-Rusyn and Byzantine Catholic migrants from Hungary.

Benedictines

Thirty-odd miles from Johnstown takes you into neighboring Westmoreland County. Here we find Latrobe, PA, the home of St Vincent’s Archabbey, the mother house of all Benedictine abbeys in the US, and very much a flourishing enterprise today. Apart from its spiritual qualities, it is essential to understanding American Catholic history. Like Loretto, that abbey has an astonishing origin story in the work of another high-octane immigrant, the German Boniface Wimmer, who arrived in 1846, very shortly after the passing of Gallitzin. Wimmer himself would unquestionably have been a great American saint had he not spent so many years systematically annoying the mainly Irish bishops with whom he had to deal. At the least, he could have been a contender. At any rate, it is a terrific story.

St Vincent’s through the years has supplied priests to many of the small towns of the larger region, which retain a very strong Catholic identity, with some fine churches and shrines. St. Mary’s, PA, has the oldest Benedictine convent in the US.

On the Border

Before his western career, Gallitzin was based in the south-central portions of Pennsylvania. This was an extremely important area as a hearth of Western settlement more generally. It produced the Conestoga wagon, and the Lancaster long rifle, which was later unfairly known as the Kentucky long rifle.

If you want to excavate the roots of Catholic America – or at least, as those roots appear in the context of the former British colonies, rather than the French or Spanish empires – then you need to relocate to this different part of the state. Visit the beautiful Conewago, a place closely associated with Gallitzin, and a critical center of early Catholic evangelism and organization. The Sacred Heart Basilica here has a very rich history.

If you are in this part of the world, a mere twenty-mile drive takes you to Emmitsburg, just over the Maryland border, where you find the National Shrine of Saint Eliabeth Ann Seton, and the National Shrine Grotto of Our Lady of Lourdes. Both attract heavy pilgrim traffic, all the more intensely in an age when sizable communities from Global South nations are so abundant in great cities such as Baltimore and Philadelphia.

Whichever part of the planned “trail” you follow, I do suggest one side venture. One surprising addition to a pilgrim route involves traveling to Boalsburg, near State College, the site of an old and inspiring Mexican statue of the Virgin of Guadalupe. This is crying to be a venerated shrine if anyone cared to pay attention to it. I have done my best to publicize it! Make your reservations now for December 2031, the 500th anniversary of Juan Diego’s original vision.

Photograph is my own work

Back to the Future

My list of places here barely scratches the surface of what is already available, and it omits so many local churches, colleges, and shrines.

Some years ago, I wrote a column asking why the United States has no great pilgrimages comparable to Lourdes or Fatima or Santiago? America, after all, still has the world’s fourth largest Catholic population. Maybe I was too sweeping about that, but most of us would struggle to think of great sites. My error might have been thinking in terms of the here and now. The great age of American pilgrimage might lie ahead of us. Would it not be wonderful if someone could construct the actual physical trails?

Photo is my own work