Dealing as it does in broadly national and patriotic themes, I think the following post is appropriate for the day before Independence Day!

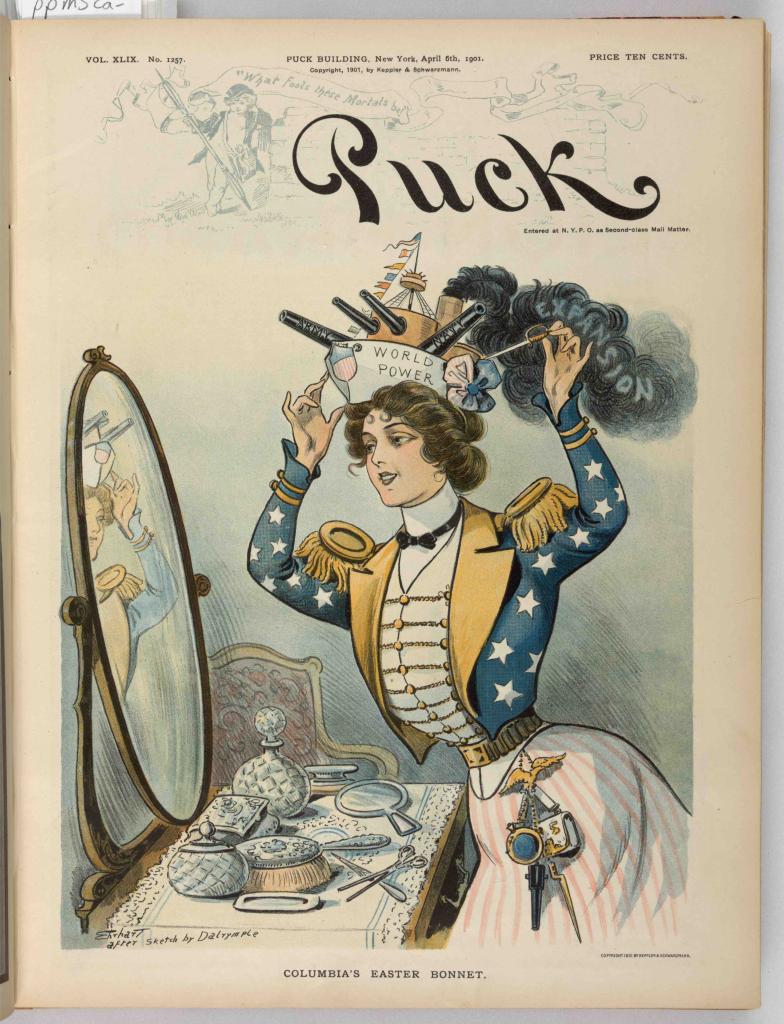

My recent blogposts have concerned the transformational developments that occurred in the US in 1893, which increasingly emerges as one of those years when the world changed utterly. That was especially true in terms of the US empire, another topic on which I have written a good deal of late. Virtually all accounts of that empire focus sharply on the year 1898, when the US fought a very unequal was against Spain, acquiring rich colonial possessions, and beginning a bloody struggle to control the Philippines. Yes, those developments were critical, but they did not spring from nowhere. They were very much part of a longer trajectory, a leap to empire, in which the pivotal year was 1893.

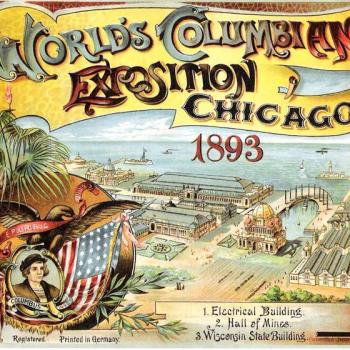

This image, and all others in this post, is in the public domain.

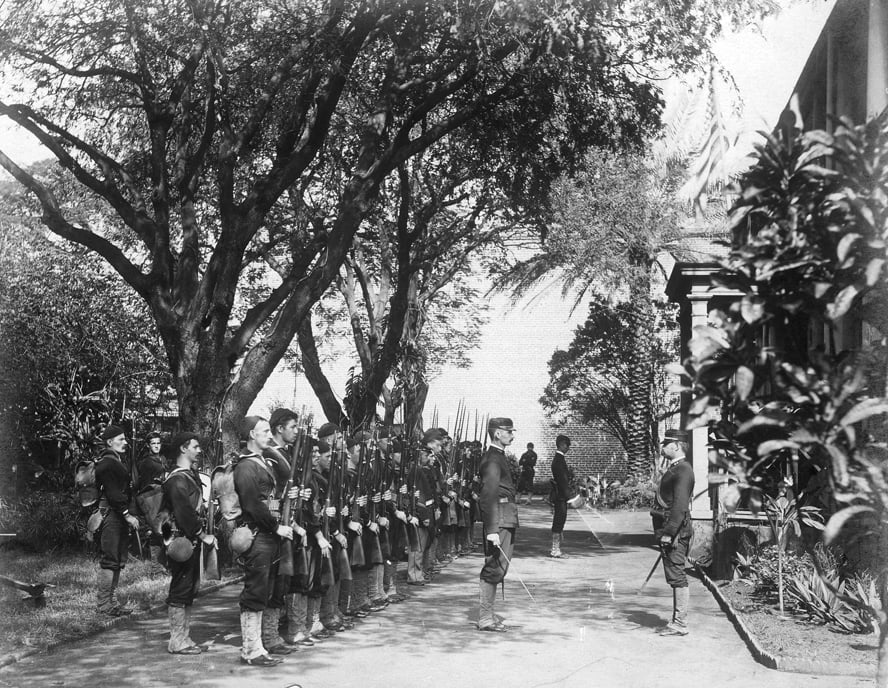

This image, and all others in this post, is in the public domain.

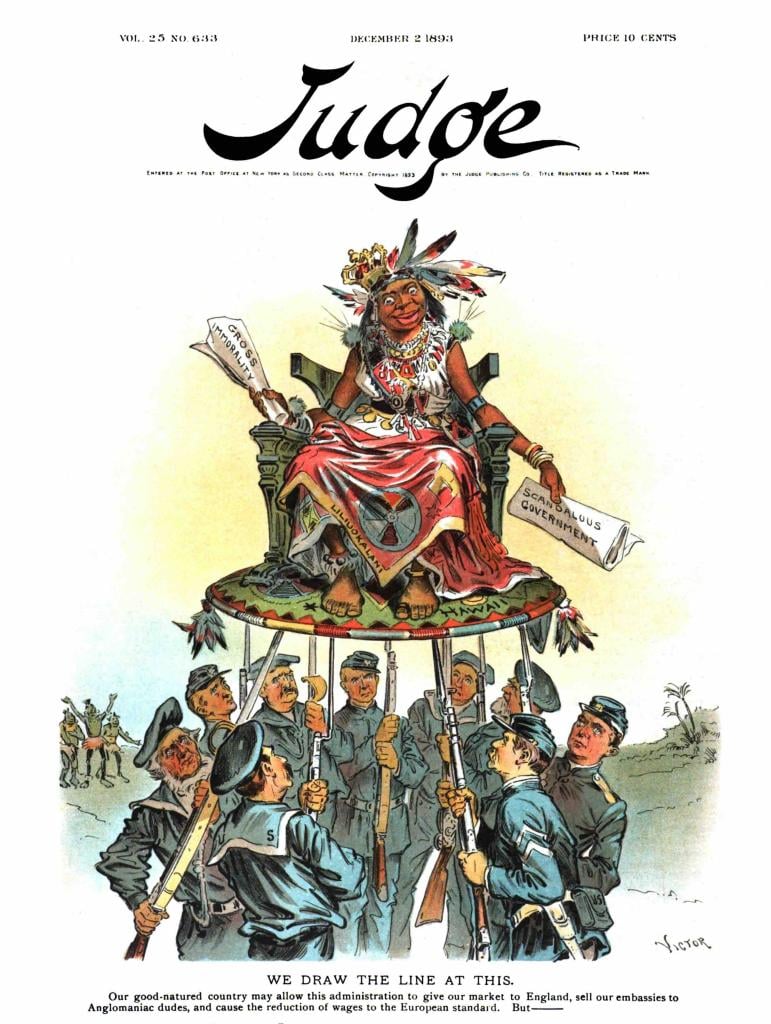

Bayonets in Hawaii

That story has several converging streams. The centerpiece was Hawaii, which technically is not viewed as part of the US empire because in 1959 it became a state, and an integral part of the USA. But that later fact does not allow us to ignore the undoubted fact that the US acquired the territory as an imperial possession, through the usual imperial means of violence and deceit.

The US acquisition of Hawaii – of the Sandwich Islands – was a long drawn out affair, beginning with the arrival of missionaries in the 1820s. Those missionaries achieved many conversions, but more to the point, they also established themselves and their families in the territory, where they came to dominate the economy. Although later generations were not themselves missionaries, these post-missionary families became rich: think of the famous Dole family, of the pineapple trade. By the 1880s, those American families and their corporate interest were posing a major danger to Hawai’ian independence.

To understand the imperial context here, recall that this prolonged consolidation of power and settlement in the Sandwich Islands coincides very neatly with the gradual American conquest of its Western continental lands.

The key figure in the final conquest was Sanford P. Dole, son of an early missionary. He enjoyed a successful legal and political career, which allowed him to pursue his vision of a sweeping Westernization of Hawaiian politics and culture. In 1887, as a justice of the nation’s Supreme Court, Sanford Dole supported the adoption of the new “Bayonet Constitution” proposed by white elites, which stripped most Hawaiians of any claim to political representation.

The decisive action came in that fraught year of 1893. US commercial elites overthrew the monarchy, supported by the presence of US Marines, and Sanford Dole became the first President of a Provisional Government. US President Grover Cleveland opposed the formal acquisition of Hawaii, but missionaries were among the leading advocates for outright annexation. When this was formally accomplished in 1898, Dole became the first territorial governor.

If we are seeking the first permanent territorial expansion of the United States outside the continental homeland – the first overseas conquest of non-White peoples – then it was in Hawaii, and the act occurred in 1893, not 1898.

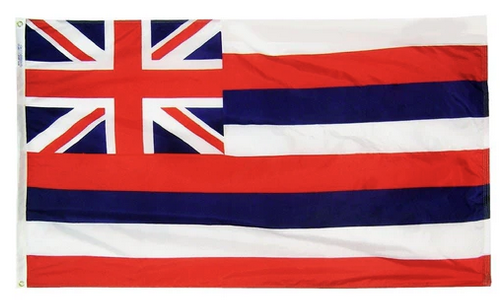

Imperial Theaters

Well before 1898 also, American elites were well aware that their expansionist activities were not going to proceed unchallenged. In the Pacific, American adventures proceeded alongside those of the British, French, and Germans, besides the older Spanish presence in the Philippines. Rivalry was inevitable, and it was exploited by Native peoples threatened by American power. In Hawaii, alarmed Native elites made heroic efforts to bring in British imperial power to counterbalance the Americans. Just see the present-day Hawai’ian state flag, which dates from 1845. The royal family converted to the Anglican church.

Of course, those efforts were of no avail, but well before 1898 they contributed to American realizations that they would very likely have to fight for their new possessions. If the Spanish war had not happened, then the US might well have confronted the British or one of the other ambitious Powers. As early as 1889, the US made a tentative move towards joining the larger imperial system when it faced a brief war scare with the Germans over Samoa. This led to an agreement with Britain and Germany to share interests in that territory. In retrospect, this marked a critical shift in US official attitudes to overseas expansion and taking new territories, and it inspired real controversy in domestic politics. The taking of Hawaii raised the stakes considerably.

To understand popular perceptions at this time – as I say, before 1898 – I cite a once much-admired fantasy book by Robert W. Chambers, which appeared in 1895. In The King in Yellow, Chambers imagines the near future as described from the viewpoint of 1920. Among the events of that turbulent era:

The war with Germany, incident on that country’s seizure of the Samoan Islands, had left no visible scars upon the republic, and the temporary occupation of Norfolk by the invading army had been forgotten in the joy over repeated naval victories and the subsequent ridiculous plight of General Von Gartenlaube’s forces in the State of New Jersey. The Cuban and Hawaiian investments had paid one hundred per cent., and the territory of Samoa was well worth its cost as a coaling station.

(Scott Fitzgerald complained about Chambers’ astonishing reputation at the time, when he was counted among “the Balzacs of America”).

In 1895, the US came very close to war with Britain, in an imperial confrontation over Venezuela.

Against such a background, the eventual war with Spain need come as no surprise. As we might say, the US had since 1893 been spoiling for a fight with a European nation.

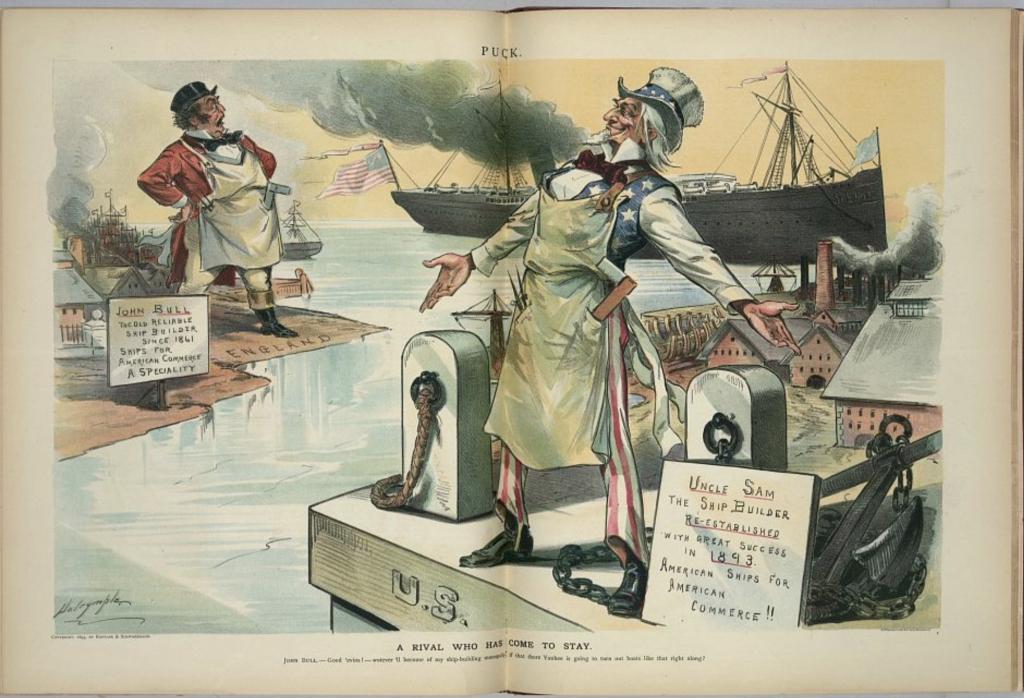

The Shape of Wars to Come

In preparing for future conflicts, the year 1893 again stands out as a turning point.

For some years, American leaders had been rethinking their military strategies. Between 1890 and 1892, Admiral Alfred Thayer Mahan published his books on The Influence of Sea Power upon History, 1660–1783 and The Influence of Sea Power upon the French Revolution and Empire, 1793–1812, which together had a huge influence of\n British and European thinkers. Meanwhile, the US suffered a shock in 1891 when it faced a diplomatic row with Chile over the killing of some sailors in Valparaiso. The US President, Benjamin Harrison, responded as any European leader might have done, and raised the prospect of sending the US Navy. That seemed like an excellent idea until it was pointed out that the Chilean Navy was at least as well equipped as the American, and was probably better. Traditionally, the US had designed its major warships for commerce raiding, rather than the hard fought battleship confrontations that were now in vogue. If you are going to practice gunboat diplomacy, it really pays to have bigger and better gunboats than the other guy.

In response, the US rapidly accelerated its military capabilities. A symbol of new imperial ambitions was the battleship Indiana, the first of a new class that was intended to compete with the best European ships of the day. Its launch, in February 1893, proclaimed US readiness to fight in the real world. Two other ships in the Indiana class, the Oregon and Massachusetts, followed quickly, again during 1893. Technically, they are all pre-dreadnoughts.

When the US fought Spain in 1898, it did not summon its victorious warships suddenly out of thin air. That Navy had been in preparation for years, and it was that new sense of imperial destiny in 1893 that had made it possible. The Oregon, for instance, fought not only in the Spanish war itself, but subsequently joined other US imperial ventures, against the Philippine insurgency, and the Boxer rebellion in China.

As with so many other topics, histories of American overseas empire should properly begin in 1893.