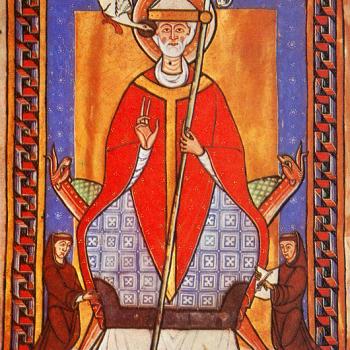

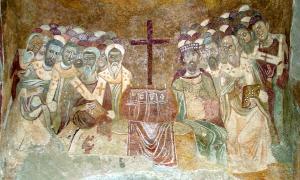

What is Nicaea about? Most modern accounts will focus on the theological debate between Arius and Alexander of Alexandria, but the nature of the controversy before, during, and after Nicaea is obscure. Thus, some scholars argue Nicaea is about the doctrine of God, others soteriology, and others think it has nothing to do with theology at all. While prioritizing a certain doctrine or focus is necessary in all historical accounts, it is striking how our narratives shape how we treat historical persons and texts, sometimes presenting a picture of the past which would be foreign to those living in it. One figure who has consistently been marginalized on account of scholar’s neat narratives, even though he was a significant leader at Nicaea, is Eustathius of Antioch—the forgotten Nicene.

Who is Eustathius?

There is a dearth of historical attention on Eustathius in both general and scholarly literature on the council of Nicaea, with only two books dedicated to the bishop (See: Sellers and Cartwright). Historically, this is odd. Before the council, Eustathius played a key role in the controversy around Arius and the shape of the debates. He is one of the first opponents of Arius (and those who defend him), after he was pulled into the disputes by Alexander of Alexandria. This led to an important role in a synod in Antioch which took place a few months before the famous ecumenical council in 325. At this gathering, over 50 bishops created an anti-Arian creed and condemned several key defenders of Arius, including Eusebius of Caesarea. While the condemnation was only provisional (to be fully settled at Nicaea), it is significant to note that Eustathius’ name is second on the list of signatures at the synod. In other words, he was present and central in the proceedings of the council (Fernández, Synodical Letter from Antioch, Fontes Nicaenae Synodi 28.1), an event which directly led to the calling of the council of Nicaea.

At Nicaea itself, Eustathius would have been viewed as a key anti-Arian leader. This is not only on account of his previous role in the debates, but also in his authority as bishop of Antioch. Importantly, Antioch was one of the most important bishoprics in the ancient world, which demanded the respect of those at Nicaea. Thus, as Lewis Ayres writes, he must have been viewed as a “key player in the discussions” at the famous ecumenical council and in the construction of the creed (Ayres, Nicaea and Its Legacy 89). While we do not know what portions he might have contributed to the creed (though, for a discussion of his potential influence, see: Parvis, Marcellus of Ancyra 59-60), we do know he is frustrated that the creed did not condemn more supporters of Arius:

But the Ariomaniacs, fearing that they should be exiled by such a great synodos which agreed on this, once they leapt forward, they anathematized the forbidden doctrine, subscribing with their own hands the agreed written statement. Once they had held onto their presidencies through such a dishonest maneuver – they should have received penance – then, sometimes secretly, sometimes openly, they advocated the already rejected, plotting against the diverse accusations. (Eustathius, Fragment 79; Fontes Nicaenae Synodi 39.3-4).

While the creed is meant to condemn Arianism, Eustathius clearly thinks some of the bishops escaped deposition by signing the creed duplicitously.

His role after the council is, perhaps, most interesting. He enters the first recorded debate over the proper interpretation of the council’s theology in the form of a pamphlet war with Eusebius of Caesarea. Socrates later writes, “Eustathius, bishop of Antioch, accuses Eusebius Pamphilus of perverting the Nicene Creed; Eusebius again denies that he violates that exposition of the faith, and recriminates, saying that Eustathius was a defender of the opinion of Sabellius” (Socrates, Ecclesiastical History 1.23.8-24.9). Further, Eustathius is the first ‘Nicene’ figure to be deposed, probably around 328 or 329, a display of the theological threat he posed to the so-called ‘Arians’. While there are a number of reasons given in the ancient sources for his deposition, including false accusations of impregnating a young woman, insulting Constantine’s mother Helena (see a post about her, here), and following the heresy of Sabellius, it is likely because he is one of the strongest opponents of Eusebius of Nicomedia and other supporters of Arius (for discussion, see: Cartwright, Theological Anthropology of Eustathius, 20-31). To add to the motivation of his opponents and eventual accusers, Eustathius is the first to write a full polemic against the ‘Ariomanics’, which was at least 8 books long (though we are only left with fragments). In sum, every Nicene and non-Nicene bishop present amidst the debates before, during, and after Nicaea would have looked to Eustathius as one of the most important bishops participating.

Why is He Forgotten?

Eustathius is overlooked not because scholars have forgotten that he existed, but because we don’t know what to do with him. First, this seems to be the case in the ancient world—only his community remembers and centers him in the decades after the council, while later writers such as Athanasius, Jerome, and Theodoret of Cyrus only mention him in passing. Second, for modern scholars, we must grapple with how weird his writings are, at least in the context of the controversy. Nearly all the extant writings about the Arian controversy across the entire theological spectrum are focused on the relationship between the Father and the Son in the trinitarian life of God. Eustathius, conversely, rarely talks about the Trinity—his focus is nearly exclusively on the incarnate Son of God, arguing that the ‘Ariomanics’ deny a human soul in Christ. Yup, you read that right—Eustathius accuses his opponents of the heresy of Apollinarius over 30 years before Apollinarius himself begins discussing this topic. Importantly, no other contemporaneous sources make this claim, either in the writings of the Nicenes and Non-Nicenes. In other words, Eustathius’ emphasis in his writings doesn’t fit into any of our narratives about what Nicaea is about, since he focuses on something which seems alien to the controversy. So, we leave him to the side as a historical enigma, an outlier who is ultimately unimportant to Nicene theology.

On the Constructive and Destructive Power of Historical Narratives

Historically, Eustathius is one of the most important ‘Nicenes’ at the council itself, yet our retelling of Nicaea has largely left him forgotten. In this, it becomes clear that our historical narratives not only have the power to elucidate the past, but also the power to distort it. Our picture of Nicaea shifts when we consider what Nicaea is ‘about’—whether Trinitarian relations, soteriology, or even politics. But what happens when someone or something doesn’t fit our narrative? Like Eustathius, they are often left out—which distorts the historical event itself.

I am not arguing we abandon historical narratives, nor feel that we simply need to catalog every person or view that is present—that is utterly impractical for the historian and theologian! But we must focus on historical figures who are often overlooked in an effort to widen our gaze to the dynamics at play. If not for Eustathius, we might not realize that Christology is an important factor for those at Nicaea. If not for Eustathius, we might not have considered the role of the divine attributes as robustly at the council (which I argued in a recent paper at a conference about Nicaea). Without Eustathius, we have a truncated view of Nicaea.

In our own historical and theological investigation, we need a view to the margins—to those who don’t easily fit. While it might make our writing a bit messier, it makes our narratives all the more plausible. Further, to look at figures such as Eustathius is to be rooted in the historical and intended meaning of the council itself. With an important event like Nicaea, it is easy for our conceptions of it to become untethered from the historical reality. There are many who use the creed without any recourse to the historical event or the bishops who shaped the creed—but to do so risks hollowing out Nicaea of all its historical meaning, employing a Nicene theology which would be unrecognizable to those at the council. Importantly, we must acknowledge that to forget the Nicenes is to forget Nicaea. If we are to properly remember Nicaea this 1700th anniversary, we must pay attention to people like Eustathius of Antioch.