I am currently writing about the year 1893, and arguing that it was of immense significance in American culture, and especially in religious matters. If you were a literate American with any interest whatever in religion or spirituality, these were heady and even revolutionary times. And for once, the religious excitement ventured far beyond the familiar frontiers of Christianity and Judaism. The range of available spiritual options broadened massively, as did the number of acceptable perspectives on traditional faith.

Modern and Fundamental

Last time I described the crucial World’s Parliament of Religions that gathered that year in Chicago, but other events in 1893 also had their religious impact. As is well known, American Christianity was transformed by debates over Biblical scholarship and the Higher Criticism, which originally stemmed from Germany. The celebrated dates here are 1910 through 1915, which marked the appearance of the ninety tracts known as The Fundamentals. These in turn gave their name to the movement known as Fundamentalism, which confronted Modernism. The most famous battle came with the Scopes Trial of 1925.

At least by implication, that is the broad chronology of Christian America’s encounter with religious modernity. But that struggle was already well under way a generation previously, and 1893 was the key year. It was the time that musings within the academy suddenly became a major presence in the mass media.

Through the 1880s and early 1890s, American scholars were absorbing the insights of Higher Criticism, and the discovery of long-lost ancient texts raised the question of exactly how Christians had determined their Biblical canon: in 1893, R. H. Charles’s translation of the Book of Enoch was the first of a deeply influential series of “falsely attributed” books, the Pseudepigrapha.

The Heresy Trial

This was all exciting enough in its own right, but conservatives were alarmed at popularizations that took these ideas outside the walled silos of academe. Such for instance was Washington Gladden, Who Wrote the Bible? (1891).

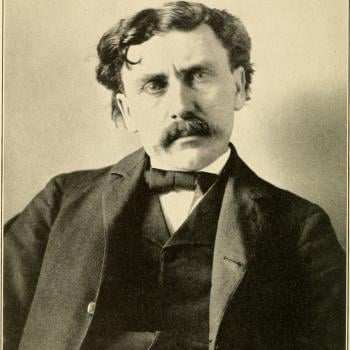

In that same year, Presbyterian scholar Charles Augustus Briggs delivered an inaugural address on his appointment as chair of biblical theology at Union Seminary, on The Authority of Holy Scripture. He declared that “there are errors in the Scriptures that no one has been able to explain away; and the theory that they are not in the original text is a sheer assumption.” Those problems included the failure or non-fulfilment of many prophecies and Messianic predictions. Neither Moses nor Isaiah were the authors of most or all of the books widely credited to them. Nor were Ezra or Jeremiah:

I shall venture to affirm that, so far as I can see, there are errors in the Scriptures that no one has been able to explain away; and the theory that they were not in the original text is sheer assumption, upon which no mind can rest with certainty. If such errors destroy the authority of the Bible, it is already destroyed for historians. Men cannot shut their eyes to truth and fact. But on what authority do these theologians drive men from the Bible by this theory of inerrancy? The Bible itself nowhere makes this claim. The creeds of the Church nowhere sanction it. It is a ghost of modern evangelicalism to frighten children.

Image is public domain, from wikipedia

Image is public domain, from wikipedia

He went on to publish prolifically, producing The Bible, the Church and the Reason (1892), The Higher Criticism of the Hexateuch (1893) and The Messiah of the Gospels (1894). For Briggs, “Reason is a fountain of divine authority no less savingly enlightening than the Bible and the Church.”

Briggs, who was combative and uncompromising, became the lightning rod for what we can call (anachronistically) a full-fledged war between fundamentalists and modernists. The immediate detonator was his 1891 inaugural address: in 1892, he faced a heresy trial by the New York Presbytery, and was acquitted. The following year, however – that is, 1893 – the verdict was appealed to the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church, which excommunicated and defrocked him. Briggs was later ordained in the Episcopal Church.

The Briggs trials were very widely followed in the media, obviously enough in an era when so much of the reading public was deeply interested in religious matters, and when so many authors were themselves clergy. Adding to public engagement and enthusiasm was the confrontational context of a formal trial, and for heresy, no less. In consequence, Briggs’s issues and causes – the whole world of Higher Criticism – suddenly achieved national celebrity.

Damning Theron Ware

Just how widely available such ideas became, and how potentially devastating even for conservative believers far removed from the great cities and universities, is suggested by Harold Frederic’s novel The Damnation of Theron Ware (1896). The book describes a young and unworldly Methodist minister who is both shocked and intrigued to encounter some educated people, including a friendly Catholic priest. Knowing he is interested in religion, they chat freely about current trends in Biblical scholarship, not realizing how world-shaking this is to him. When Ware talks about the patriarch Abraham, they are appalled to hear that anyone could be so ignorant as to treat those Biblical stories seriously:

“I fear that you are taking our friend Abraham too literally, Mr. Ware,” he said, in that gentle semblance of paternal tones which seemed to go so well with his gown. “Modern research, you know, quite wipes him out of existence as an individual. The word ‘Abram’ is merely an eponym—it means ‘exalted father.’ Practically all the names in the Genesis chronologies are what we call eponymous. Abram is not a person at all: he is a tribe, a sept, a clan.”

Ware’s learned friends see the Biblical world wholly in the context of global mythologies:

You see, there is nothing new. Everything is built on the ruins of something else. Just as the material earth is made up of countless billions of dead men’s bones, so the mental world is all alive with the ghosts of dead men’s thoughts and beliefs, the wraiths of dead races’ faiths and imaginings.

The Christ-Myth

The priest then discusses the Mesopotamian deity Marduk, whom he presents as a proto-Christ figure, and one of many:

He was the young god who interceded continually between the angry, omnipotent Ea, his father, and the humble and unhappy Damkina, or Earth, who was his mother. This is interesting from another point of view, because this Merodach or Marmaduke is, so far as we can see now, the original prototype of our ‘divine intermediary’ idea. I daresay, though, that if we could go back still other scores of centuries, we should find whole receding series of types of this Christ-myth of ours.

“This Christ-myth”! For Ware, the idea is so explosive as to detonate something like a conversion experience:

Theron Ware sat upright at the fall of these words, and flung a swift, startled look about the room—the instinctive glance of a man unexpectedly confronted with peril, and casting desperately about for means of defence and escape. For the instant his mind was aflame with this vivid impression—that he was among sinister enemies, at the mercy of criminals. He half rose under the impelling stress of this feeling, with the sweat standing on his brow, and his jaw dropped in a scared and bewildered stare. Then, quite as suddenly, the sense of shock was gone; and it was as if nothing at all had happened. …

Ware begins to experience

a vague premise that there were a great many different kinds of religions—the past and dead races had multiplied these in their time literally into thousands—and that each no doubt had its central support of truth somewhere for the good men who were in it, and that to call one of these divine and condemn all the others was a part fit only for untutored bigots. Renan had formally repudiated Catholicism, yet could write in his old age with the deepest filial affection of the Mother Church he had quitted. Father Forbes could talk coolly about the “Christ-myth” without even ceasing to be a priest, and apparently a very active and devoted priest. Evidently there was an intellectual world, a world of culture and grace, of lofty thoughts and the inspiring communion of real knowledge, where creeds were not of importance, and where men asked one another, not “Is your soul saved?” but “Is your mind well furnished?”

Harold Fredric’s novel was very well known, and in his early years, Scott Fitzgerald regarded it simply as the best American novel.

Next time I will talk about one of the most important and innovative books in the history of American religion, which also appeared in that astonishing year of 1893. And it was by a woman.