In 1893, Congregationalist minister Josiah Strong (1847-1916) was a leading figure in the Social Gospel movement that was such a prominent feature of American Christianity in the late nineteenth century. The great church historian Sidney Ahlstrom calls him “a legend in American history, as both a religious and a secular figure.” But by modern standards, his ideas combined two approaches that to us seem utterly irreconcilable, of radical social reform and scientific racism. His story epitomizes a critical moment in American Protestant history.

The New Era And The Coming Kingdom

Strong, like other Progressive-minded clergy, urgently wanted the churches to respond to the crying needs of the swelling cities, to fight corruption and poverty, to eradicate slums and saloons, and to build good housing. His book published in that year, The New Era; Or, The Coming Kingdom,is a sweeping and very influential manifesto of Social Gospel theories, and of specific campaigns for reform. Only thus could the working masses be brought back to the churches.

Conservative evangelicals hated such ideas. As Ahlstrom says, he was

denounced as one who betrayed biblical teaching on the Kingdom of God and put millennial doctrines at the service of social reform and foreign policy. To those many Protestants in almost all denominations who think of the churches as essentially spiritual institutions which should be concerned primarily with reaching and converting individuals, Strong was seen as a meddler in secular affairs which are not the proper concern of organized Christianity; in addition he was blamed for subverting the aims of the Evangelical Alliance by making it an engine of theological liberalism and social activism. … If the Social Gospel and its secular corollary, Progressivism, deserve any credit, then so does Josiah Strong. Indeed he more than any other made it possible to speak of the Social Gospel as a movement.

In modern liberal terms, so to speak, Strong sounds like one of the good guys. But in the same book, The New Era, Strong wrote at length about the glories and the power of the Anglo-Saxon race as the summit of human accomplishment – and as a race, not just a cultural tradition. He speaks repeatedly of bloodlines, of breeding, of human stock, both superior and inferior. The reader should draw vital lessons:

The importance to mankind and to the coming Kingdom of guarding against the deterioration of the Anglo-Saxon stock in the United States by immigration. There is now being injected into the veins of the nation a large amount of inferior blood every day of every year. … He does most to Christianize the world and to hasten the coming of the Kingdom who does most to make thoroughly Christian the United States.

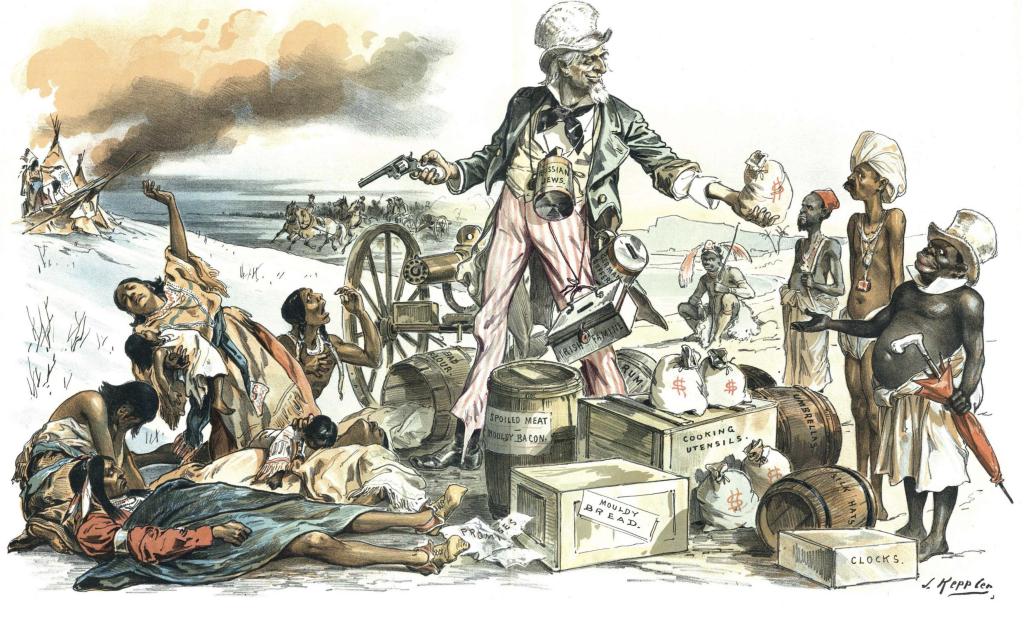

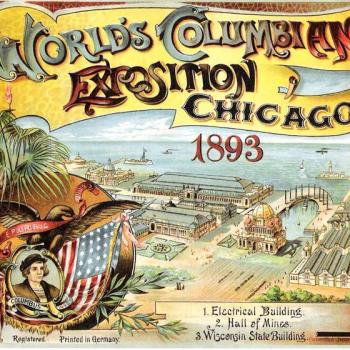

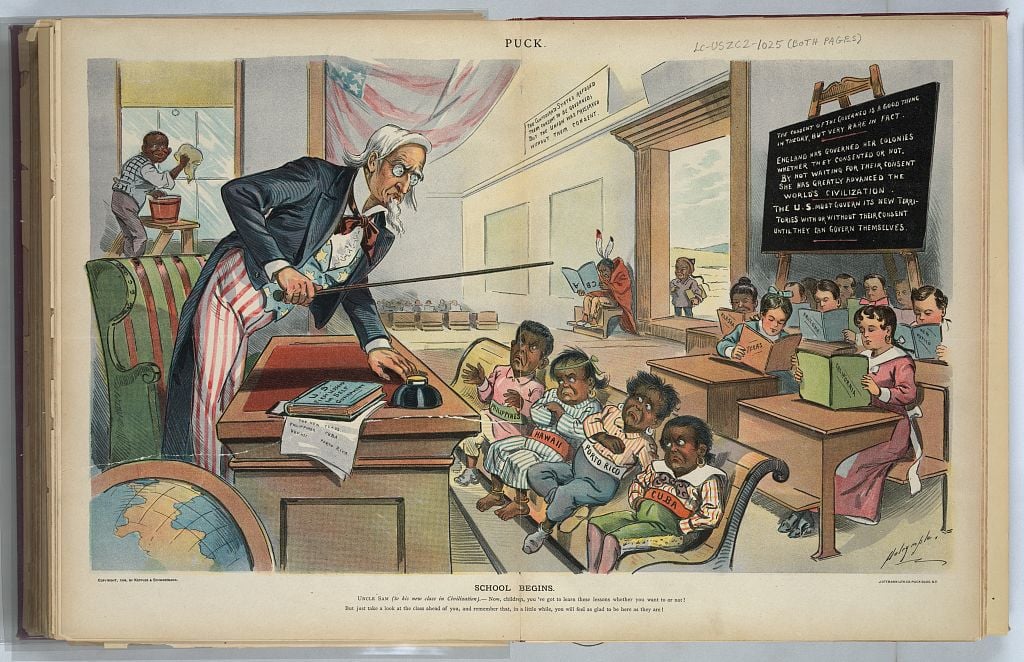

This image, together with all others in this post, is in the public domain.

This image, together with all others in this post, is in the public domain.

The Problem of Labels

Many modern readers find a serious disconnect here, and particularly in terms of applying labels. We live in a world in which racial theories and biological classifications have moved wholly beyond the acceptable political spectrum, and we would presumably describe Strong’s opinions as lying on the extreme Right. At the same time, we think of the Social Gospel as part of a liberal progressive movement, which at times advocated political interventions that surely belong to the Left. Those progressive causes commonly included women’s rights, the suffrage and Temperance, and in each of those case women campaigners were likely to cite biological and racial arguments for change. Often too, they were frankly Nativist (I will cite examples in upcoming blogposts).

In that seeming combination of opposites, Strong in fact was very typical of his age, and especially of religious thought. Put simply, those apparent opposites absolutely were not opposites to him, or to a great many of his educated contemporaries. In the intellectual world of the time, racial and biological theories and rhetoric enjoyed enormous significance, to the point that they have to be included in any credible account of the religious or reformist world-view. For many leading figures, racial and religious thought were inextricable. For my present purposes, understanding such ideas is so critical because they so often manifest themselves in the thought and writing of 1893, and in ways that might seem startling or even shocking.

If you ever find a way to write the religious history of this era without taking full account of biological and racial theories, do let me know: I can’t.

The Hierarchy of Races

Any account of nineteenth century thought will highlight the year 1859 and the publication of Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species, which undeniably created furious debate among religious believers. But even some of the religious and clerical thinkers who denied Darwin’s specific theories absorbed many ideas that we think of as part of the evolutionary package, and its subsequent developments. Most such ideas centrally used the concept of race, and the factors by which races changed over time. The key name here was not Darwin but his half-cousin Francis Galton, who in 1883 defined the science of eugenics, “the study of all agencies under human control which can improve or impair the racial quality of future generations.”

Essential to this structure was the idea of classifying existing human types as belonging to higher or lower races, and indeed as more or less fully human: Australian Aborigines usually featured very low in this scheme, with Black Africans scarcely better. In a notorious passage in his Descent of Man (1871), Darwin rated the intermediary types that lay between full humanity and primitive apes:

At some future period, not very distant as measured by centuries, the civilized races of man will almost certainly exterminate and replace throughout the world the savage races. At the same time the anthropomorphous apes, … will no doubt be exterminated. The break will then be rendered wider, for it will intervene between man in a more civilized state, as we may hope, than the Caucasian, and some ape as low as a baboon, instead of as at present between the Negro or Australian and the gorilla.

At the other end of the spectrum were the higher races, which demonstrated their evident superiority through their accomplishments, and their growing numbers and political power, which was so apparent during the age of European empires. In the Anglo-American mind, the summit of creation was represented by the Anglo-Saxon peoples, which together were conquering much of the world’s surface and dominating its peoples, demonstrating starkly the “survival of the fittest.” Besides Anglo-Saxonism, “Nordic” terminology was also gaining favor.

Lesser races might ultimately fade away and vanish, or they might survive, but in the meantime, their position in regard to the higher races was that of restless children as opposed to mature adults. The Anglo-Saxons literally were the grown-ups in the room. And as with unruly children, they could in no sense expect any kind of equality of treatment, of rights, or of self-government.

Falling Back

But those relative positions on the evolutionary scale were not fixed, and higher races could decline or fall. That idea of hereditary influences shaping communities for better or worse was by no means new to Americans. In 1877, Richard Dugdale published his study of a multigenerational problem family in The Jukes: A Study of Crime, Pauperism, Disease and Heredity. In the same year, Italian scholar Cesare Lombroso presented his theory that criminals represented a kind of evolutionary throwback to primitive and violent beings, and that atavism was reflected in their distinctive bodily features. This owed much to the highly publicized discovery of Neanderthal remains in the 1850s. Lombroso, quite seriously, thought that the common criminal fashion for tattooing themselves was convincing evidence that they were throwbacks to primitive races.

A race could fall back and degenerate, or it could improve, and policymakers had a major influence on that choice of rival paths. Two issues in particular focused public fears at the end of the nineteenth century, as potential blights on the future of the race, namely sexual diseases – above all, syphilis – and alcoholic drinks.

Religion and Racial Decline

At this point, it might reasonably be asked what any of this had to do with religion, and specifically the Protestantism that was the hegemonic faith of nineteenth century America? Drawing on memories of the Scopes Trial and the film of Inherit the Wind, we might assume a straight conflict between Darwinian evolution and Biblical literalism.

In fact, not only did prominent clergy support such opinions, they were their primary exponents in US culture. More specifically, the key thinkers were Congregationalists, who found such ideas very congenial with their Calvinist roots.

One of the most respected and influential American theologians of the time was Congregationalist Horace Bushnell, whose book Christian Nurture (1861) made some far-reaching observations about Christian expansion and the fate of lesser nations. At this early date, just two years after Origin of Species, he stressed that that Christian growth was a matter of population expansion rather than mission, and that this expansion was the result of selection and evolutionary advantage, that is, of “fitness.” Particular developed and maintained characteristics, whether civilized or savage, and the advantages of civilized races allow them to grow and spread at the expense of inferiors. Christians, he believed – and by this he invariably meant White American Protestants – stood at the highest end of such a racial hierarchy. As a race achieves new levels of “personal and religious character,” so it increases its “populating power,” which allowed it to outnumber and dominate less successful and “fit” groups, such as Catholics and Latinos. He praised “The Out-Populating Power of the Christian [that is, White Protestant] Stock.” Over time, those lesser races had to submit and accommodate the successful race, and they faced a real chance of extinction.

Josiah Strong and the Anglo-Saxons

More prestigious and celebrated even than Bushnell was Josiah Strong. In 1885, he achieved a major bestseller with the book Our Country: Its Possible Future and Its Present Crisis, which combined evangelical thought with imperial ambition, combined with racial, eugenic, and Social Darwinist thought.

For Strong, the Anglo-Saxon race was destined to dominate the world, and the US would be at the core of such a project. Indeed, the aggression and violence of which foreigners so often complained about in the US context constituted a positive evolutionary feature that promised well for the future of that race. Citing Bushnell, he asked rhetorically, “Is it manifest that the Anglo-Saxon holds in his hands the destinies of mankind for ages to come? Is it evident that the United States is to be the home of this race, the principal seat of His power, the great center of His influence?”

In the context of the time, that Anglo-Saxon race was evidently the world’s most successful:

Then this race of unequaled energy, with all the majesty of numbers and the might of wealth behind it — the representative, let us hope, of the largest liberty, the purest Christianity, the highest civilization — having developed peculiarly aggressive traits calculated to impress its institutions upon mankind, will spread itself over the earth. If I read not amiss, this powerful race will move down upon Mexico, down upon Central and South America, out upon the islands of the sea, over upon Africa and beyond. And can anyone doubt that the result of this competition of races will be the “survival of the fittest”?

In language that has chilling connotations for modern readers, Strong suggests that “in what Dr. Bushnell calls ‘the out-populating power of the Christian stock,’ may be found God’s final and complete solution of the dark problem of heathenism among many inferior peoples.” Yes, he did refer to a final solution.

The Destiny of the Race

Hard to believe, but the 1891 edition of Our Country was even more explicitly biological and Darwinist, based as it was on the findings of the 1890 census. So was his The New Era of 1893. In a chapter on “The Destiny of the Race”, he sounds the alarm about racial degeneracy and the rise of inferior racial stock, and “the survival of the unfittest”:

Thus the weak members of civilized societies propagate their kind. No one who has attended to the breeding of domestic animals will doubt that this must be highly injurious to the race. It is surprising how soon a want of care, or care wrongly directed, leads to the degeneration of a domestic race; but, excepting in the case of man himself, hardly any one is so ignorant as to allow his worst animals to breed. And civilization not only preserves the defective classes and permits them to propagate their kind, it also tends to reduce the fecundity of the more highly cultivated. The poor are apt to have large families, the rich small. … The Mountain Whites of the South, who are little more than semi- civilized, do not count a family of a dozen or fourteen members large; and sometimes there are found twenty or more children of one mother. On the other hand, we hear laments that the old New England stock is dying out. Certainly the families of that stock are much smaller than they were a few generations ago and afford a painful contrast to those of alien blood who are transforming New England into a New Ireland or New France.

It is hard to exaggerate Strong’s influence in shaping US opinion, and especially in the ideology of Anglo-Saxonism. His arguments surfaced repeatedly in the grand national debates over the creation of an American empire after the Spanish American war. Religious critics of empire especially recognized that they had to fight hard against what they saw as a dreadful merger of Calvinism and Darwinism.

Josiah Strong and the Social Gospel

And as I have said, Strong was also a critical figure in the Social Gospel movement. To summarize quickly, this movement originated in the 1880s (the term first appears in 1879). It attracted such paladins of American Protestantism as Washington Gladden and Walter Rauschenbusch, and any account of the movement normally gives equal prominence to Josiah Strong, and specifically to Our Country and The New Era. Already in 1885, Our Country had laid out the seven components of the national “Crisis,” seven deadly dangers facing the nation: Catholicism, Mormonism, Socialism, Intemperance, Wealth, Urbanization, and Immigration. The Social Gospel approach was later popularized through Charles M Sheldon’s novel In His Steps (1896), which coined the famous question What Would Jesus Do?

For us, the combination of racial theory and reformist zeal seems incongruous and even baffling, but the links become apparent if we pursue the social activism of the coming decades. Christians had long denounced drink, and as I will show, the Temperance movement enjoyed a massive revival from the early 1890s. Unlike in earlier eras, they now placed a central emphasis on the racial harm of alcohol, and the damage caused to new generations of children. Christians had likewise campaigned against sexual immorality, but again, that militancy now found a biological focus, in preventing the spread of sexual diseases and hereditary harms and the undermining of the Anglo-Saxon racial project.

Morality, as defined in its White American Protestant mode, actually supported the defense and building of the race. And in all these individual campaigns, women played a critical role, as the bearers of the ascendant new race, who must be preserved from sexual diseases and alcohol-fueled abuse. Feminists, suffragists, and Temperance advocates alike all drew heavily on racial and biological ideas, which were likewise immersed in Nativism and anti-Catholicism.

In modern times, people have been shocked to find just how deeply the birth control movement of the Progressive Era was immersed in eugenic theories: witness the embarrassment about Margaret Sanger. But this connection was absolutely what we would expect of the era.

So to rephrase Charles Sheldon’s question as it might have appeared in that era: What Would Jesus Do To Improve the Race?