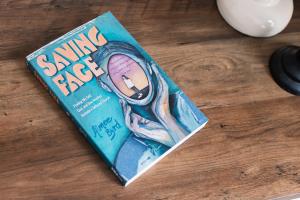

I agreed to interview Aimee Byrd about her new book, Saving Face: Finding Myself, God, and One Another Outside a Defaced Church (Zondervan Reflective, 2025) with the caveat that my training is as a historian, not as a clergyperson or counselor.

I offer that same caveat here. And that’s because little about Byrd’s book is historical, outside of references to her own personal experiences. That’s not to say it’s not academic—some of it is, with references to C.S. Lewis, Richard Rohr, and other theologians. The rest is intensely personal and reflective, interspersed with recollections from her childhood– what Byrd calls “storied memories” — journal entries, and personal anecdotes. The result is an intentionally uneven book, one that in form insists on authenticity and honesty.

“I used to think truth was a doctrinal matter, that truth was certainty. It was objective and dehumanized” she writes, but “I’m learning that I was only looking at the outside of things.” Truth is Jesus, she says, and we prepare to see His face by practicing seeing truth in ourselves and one another. Byrd’s titular argument, which she borrows from C.S. Lewis’ Till we Have Faces, is that we cannot really see ourselves; we can only be beheld and known in the faces of others and, ultimately, of God. That, then, she says, prepares us to see God more clearly. While some may feel the delivery borders on the solipsistic, what Byrd’s work is challenging is the falsity and abusiveness so apparent in the modern church, which, she claims, obscures the face of Christ. Byrd repeatedly points out the refusal of those in power to risk vulnerability, to name their own weaknesses, theological and otherwise. But while it’s a strong critique, Byrd’s tone is not condemning–she seems to really hope that those claiming the mantle of Christ can risk knownness and find their true, weak, wrong selves beloved by Jesus.

In my mind, the strength of the book is its extended feminist interpretations of Scripture, namely from Deuteronomy and Song of Songs, where Byrd teases out new meanings and questions, revealing her natural curiosity and love for beauty. Those seeking spiritual vulnerability and engagement with deep questions of truth and beauty will enjoy this book; those seeking simple answers or a spilling screed against the any denomination will not. I am thankful to have read it and for my conversation with Aimee—which follows in its entirety, edited only for clarity.

AB: Hello!

AQ: Hey, Aimee, how are you?

AB: Doing good. Can you see me?

AQ: Hey, yes, how are you? So nice to meet you. I am actually not trained in religious studies, I’m a historian by training, but I read and really enjoyed your book.

AB: Thanks!

AQ: Yeah. Well, I have like five or six questions. It shouldn’t take too long, but feel free to answer or veer in whatever direction you want. To start, I would love to hear why you decided to write such a deeply personal book, especially after all the criticism you encountered online. Where did you find that courage and why did you decide to write it this way?

AB: Yeah. I think after everything I went through, I had to really ask myself, just like, what matters to me. Like do I even want to keep writing? And I share a little bit in the book about how, it’s easy to look at those that harmed me in the church and keep telling myself the story that those are the bad guys and I’m the victim. And to stay on that loop, But, while a lot of that’s true, I needed to look at myself and what attracted me to that kind of denomination and that kind of church. And how did I not see how harmful it was. You know, those were some really hard questions to ask and I think at my age now– I was 48 when I wrote the book–I think I’m just at a point where

I didn’t want to write anything if it’s not going to be what really matters, and what would really be helpful. So it was hard for me in a lot of ways to write, but I feel like one thing that kept me writing was hearing from so many other harmed people in the church and hearing the encouragement from them to keep writing because it was helping them to name things and to heal as well. And to find hope. I think the vulnerability of it helps readers to also be vulnerable and the whole topic of the book is a very vulnerable topic. I’m using the face as a metaphor, really, of integrating our true self and to help draw that out of one another, and to find Christ in our faces. So I felt like it needed to be a vulnerable book.

AQ: Yeah. It’s not just what you’re saying, but how you wrote it. You write that the book is a combination of “storied memory, journaling with God, interactions with the faces of others, and relooking at the Scriptures.” And I think even in form it’s an unusual book because you have these sort of extended memories and dreams, interactions with your parents, kind of raw journal entries and then deep exegesis–

interesting, feminist exegesis–all together. Why did you decide to write it in this way? Why put it all in there? And then what are you hoping readers encounter not just in the content, but in the form?

AB: Right. Yeah, I didn’t know if I would pull it off because I am blending a lot of genres. And it has a lot of personal memoir in it, and a lot of creative writing, and contemplative writing, which is a different style of writing than I had done in my other books and, again, I think this is really just where I am in my spiritual life and as a writer now. I started writing trying to encourage women to become more theologically-minded and to encourage the leaders in the church to invest in women. And so I wanted to sound precise and intelligent and, you know, get T’s crossed and I’s dotted. But now I see I was putting so much stock in theological precision and propositional statements, I began equating that even with like spiritual maturity.

AQ: Yeah.

AB: It was so, so disillusioning, then, to see leaders in the church [who were] so spiritually immature and emotionally immature. So what I did is I really went back to why I love writing, and really what’s in me. I feel like I’m a creative, I really am. And so I felt like I was just more in tune, not only with who I am and who I wanted to be as a writer, but also I think what helped me with my own healing so much was to let go of looking for the precision. And look for beauty.

AQ: Hmm.

AB: And so I wanted to create something beautiful too, not just theologically correct, because I think that’s where I’m finding Christ now. That’s where the healing is. And that really is an invitation into goodness. So, I think my genre is also a display of maybe our path to spiritual maturity and growth doesn’t look like just getting all our doctrine right or being in this denomination or that denomination, as important as doctrine is. I’ve talked in one podcast about how God could just create us and download us with the truth, right? And but we live this life, and I think he’s making us ready for reality, making us ready for the truth. And so, there’s so much beauty and even suffering involved in that. And I wanted to get into that, and I wanted my writing style to reflect that as well.

AQ: Yeah, it’s interesting. People who study the Bible should know that better than anybody else. It is not a systematic theology.

AB: No. Right. There’s so much narrative. I share in Saving Face–and in my last book, Hope in our Scars—about the Song of Songs. It just really speaks to my heart and my healing. And you know, it’s allegory. It’s poetry. It’s song, it’s metaphor. That does something that the propositional statements can’t do. It awakens us. It directs our longings.

AQ: Yeah.

AB: I can find my story in in the story, in the song. It tells the whole story of Scripture too. Artistic ways of communicating can teach us in ways that just doctrinal statements can’t.

AQ: Yeah, I agree. In that search for beauty is also, this search for what I would call authenticity. It seems like a main theme of your book is authenticity with self, authenticity or honesty with others, and then ultimately, of course with God, the face of God, which you talk about a lot. I liked this line I think you borrowed that “prayer is a form of secret telling to God.” Can you talk a little bit about that? There’s definitely. beauty woven throughout the book, but not all the statements are beautiful and not all of our prayers are beautiful. Can you talk about that tension between beauty and what I would call authenticity? You may have a better word for it.

AB: Yeah. You know, I grew up being taught how to pray. They teach you with the acronym ACTS: adoration and confession, thanksgiving and supplication. And now I’m like, oh, my gosh, that’s so contrived. You know, we don’t talk to our parents like that. We don’t talk to our loved ones like that, our friends. I don’t think God wants us to come to him with some formula. We come to him so many times in a contractual, transactional way. That’s one reason why I shared my journaling. Because my journaling turned into a back and forth, weaving in and out of conversation with God. Renita Weems talks about her journaling and prayer. And she calls it “stuttering before the holy” because you know, you realize you’re just saying a bunch of junk a lot of the time. You’re just getting it out because you have to get it out of your heart and out of your mind. You have to get all that stuttering out to finally get to what you really want. It takes a while to pray as, a form of secret telling, but in a sense of we’re keeping those secrets from ourselves too. It’s encounter. I think a lot about Teresa of Avila. In her book The Interior Castle, she talks about prayer and the spiritual life and thinking of our soul as a castle with many rooms. She talks about how God dwells in the soul of every believer. And you know, we believe this and we say this, but to really contemplate on that there’s a piece of heaven in each one of us, because it’s where God’s dwelling. And not only that, he delights to dwell there. To think of it in those terms then, I think also of the intimacy of how God knows me, how God knows my soul. I’ve covered it up with so many personas and ways that I thought I was supposed to be and you actually start tricking yourself into thinking that that’s who you are. And so I think having that time and the journaling really helps. We’re also uncovering our own secrets about who we are.

AQ: Mm hmm.

AB: Some of it we have to confess before God and some of it is quite beautiful. And we’ve hidden it away. So he wants to show us all that. That’s what I’m getting at there with the secret telling. And even how we can do that too, in conversation with one another to help one another create containers, create spaces, where we can be vulnerable and discover more about ourselves. Because I really can’t learn about myself unless I’m in relationship with other people.

AQ: Yeah. It’s sort of like acting. I grew up in the PCA and am familiar with some of that good theology/ good behavior. But, as you were talking, it seems that we can buy that our projection of the “Good Me“ is ourself. But underneath that, if we’re believers, then, like you were saying, the same Jesus that lives to make intercession for us at the right hand of God is also within us. And so we have to get past that [Good Me] so we can encounter God in our deepest selves. It’s a really beautiful idea.

AB: Yeah. Thank you. The “Good Me” is the me that I thought I was supposed to be.

The righteous Aimee. I worked hard to build for a long time and then realized that a lot of that is a mask. You start convincing yourself that you are that person, and the ugliness of it really –besides the lack of self-awareness–is the self righteousness. You really start feeling that.

AQ: Mm hmm. Yeah. And in your case, you didn’t have much choice but to confront it after your experience with the [OPC] elders [at a previous church]. And yet you’ve used that experience to invite people, and those people, to shed that [self-righteous] persona.

AB: Yeah. I mean one can hope, right? It’s really hard when you’re in abusive situation like that. You have to remove yourself from abuse. On one hand you want to keep yourself emotionally, mentally, psychologically safe. But on the other hand, like you know, there is this part of me that hugely longs for reconciliation and, you know, wants them to see what I was able to see through it.

AQ: A moment ago, you mentioned Renita Weems and Teresa of Avila. You quote frequently these inspirations: Richard Rohr. CS Lewis, of course, probably the main one in the book, Clare of Assisi, Frederick Buechner. Can you talk about these sources of literary and spiritual inspiration?

AB: Yeah. I’m a major reader. I love to read and I think that these minds, the names that you were just sharing, they’re just great thinkers outside the box. They’re not going to give you the systematic theologies. You read a Buechner sermon and it is nowhere near the three-point sermon or something today. And Buechner talks a lot about digging up our secrets. And that really attracted me just reading these types of more contemplative writers, both new and old. It’s a community that I wanted to be in conversation with, but also to introduce to readers who haven’t heard of them before, read their stuff.

AQ: C.S. Lewis, of course, is pretty familiar to many evangelicals, but maybe not Till We Have Faces.

AB: Exactly, yeah. I don’t think Til we Have Faces is as popular as some of his other works. But I read it in my twenties and right away I was like, “this is an amazing story.” I couldn’t believe to how well C.S. Lewis could pull off writing with a female voice. That blew my mind. I mean, he’s a great writer, but he’s an old white guy. He didn’t exactly live in a time of super feminist ideas or anything either. I just felt like it was believable. And then the story itself was amazing. So, I share in the book that I’ve been saying now for 25 years –over 25 years–that that’s my favorite novel. But I hadn’t gone back and read it again. And so in my forties I went back and read it again, and it definitely confirmed that it’s my favorite novel. I got so many treasures out of it. I really resonated with it, with a new character.

AQ: Mm hmm. Yeah, I love that. So much of the book engages this search for a church community. Also, by the way, I laughed out loud at this line: “I know church is for weirdos too, but why are there so many?” I was like, “Exactly! Why are there… more?” I mean it makes sense when you think about the church as primarily a place for sinners, but still.

So I’d love to ask you to describe, especially for Anxious Bench readers who might not know a lot of y’all’s story, that process of looking for a church. And then you find yourself in a mainline Methodist congregation. And so I’d also love to know: are you still there? What are their tensions that are remaining for you in that space? Can you talk also about why you stuck with the church, and really longed for it, despite the church hurt and abuse you experienced?

AB: Yeah, Again, Song of Songs really helped keep me going as far as looking for a church because you have this this allegory of Christ and his people being told through the man and his lover, the woman. The woman represents God’s people and

I love how the woman’s voice is dominant in the song. She opens it. She closes it. Even Gregory of Nyssa called her the teacher. She’s teaching us so much in this story and a lot of it is like a hide and seek in parts: Where is God? Where are you right now? I can’t find you. But he’s like right there. So I felt like that was an encouragement for me, that He is among his people and I want to find him.

What I experienced, yes, it was a lot of disillusionment, but I knew that it was just so counterfeit. So I wanted to find a good church community and I catalog through the book the stumbling about in doing that, which was really hard. Because it’s extremely vulnerable when you’ve been through such public spiritual abuse to even visit churches and even talk to the pastor. I wonder: Are they going to Google me? And am I going to look like a big, fat troublemaker to them? And do they not want to invite this kind of chaos into their church?

And I did bring chaos into a lot of spaces that hosted me as a speaker. Not because I wanted to, but because my harassers would harass them. They would also threaten to bring charges against them and things like that. It was very disturbing. So that was extremely hard. And I live in an area where there are a lot of churches, but–coming from what was supposed to be complementarian denomination, but, you know, it’s just patriarchy– I couldn’t go in any space like that again. Even in trying to follow the proper church process with my case my voice was completely taken by the men. They spoke for me.They made the decisions behind closed doors or talked about it behind closed doors.

I just wasn’t a part of any of it. So, that narrows down where you go.

And, you know, denominations that have been known for patterns of abuse and not doing anything about it. That narrows it even more. We walked into a lot of Christian nationalist spaces: community churches, Bible churches. There’s the American flag right there up there in the front of the church and talking about voting and things like that.

And then there was a group of churches more for people who’ve been harmed or are deconstructing, really reaching out to that group. However, a lot of them were following the teaching of Andy Stanley, unhitching from the Old Testament. And here I am really gleaning from the Song of Songs and thinking ‘man, they’re missing the juice, just the whole richness to the biblical narrative and the unfolding of God’s word by not including any of the Old Testament.’ So that was very discouraging too. And a lot of these churches you go in and it’s just like the band’s a rock band, and then there’s a “sermon”, which is more like a motivational speech, and then that’s it. There’s not even a benediction. There’s no congregational prayer. I was starting to really hunger for some liturgy. Just Christ in the liturgy.

So a pastor friend of mine asked me, “why don’t you try a mainline church? You might not agree with everything, but you know what to expect with the liturgy.” So we did.

We tried the Methodist Church and there was a woman pastor and I share that experience. I wasn’t looking for a woman pastor. As a matter of fact, I did not want to go to a church with a woman pastor because of my haters. I just knew that it would be an “I told you so. This was Aimee’s trajectory the whole time.” And it wasn’t. But I kind of got pushed into it in some ways, and I’m very thankful. And so we’ve been going to this Methodist Church. We’ve been there for a while now. We’re not members and we’re not really Methodists. So I still feel like it’s a holding place in some ways, but I’m very thankful for it. And I don’t know what’s ahead. But we’ve been treated well there. There’s a lot of wise people at that church. And I appreciate Pastor Katie a lot.

But we still have had trouble connecting, and we’d love to see some more diversity. It’s a very white church. And so, we’ll see. I struggle and wrestle with God. But Christ is there. And that is that’s fabulous. So I’m thankful and it’s taken time. I thought when I got out of my denomination, of my church, I knew that I had a lot of trauma to unpack. I knew I need to take time for healing. And it even feels weird to say that, it’s hard to say those words, but I thought, ‘yeah, probably, like maybe, a whole year. And joke’s on me. It takes longer than that. And so I am very thankful to not feel like I have to be the person doing all the things in church, to unlearn and to learn. And there’s so many beautiful surprises there.

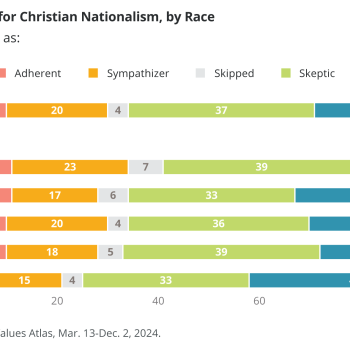

AQ: First of all, thank you for sharing that. I feel like there are a lot of people, especially women, who are recognizing these sort of power politics, a lot of young people who are rejecting white Christian nationalism in these spaces. There are also people moving into them for other reasons, or into charismatic spaces. There’s a lot of reshuffling right now in American religious life and churches.

AB: Right, yeah.

AQ: And so, it’s an interesting way to think about church. Is church a reflection of who I am, my identity? Which is how we think about it so often. Or is church space where we can encounter God with other people, and we can serve?

AB: Right. Yeah, And the encountering God I’ve just learned how different that is from my expectations before. It might be God hiding in plain sight, right? Like you’re looking for some big, profound thing in the sermon or whatever, this emotional experience while you’re singing, or in the in the communion or something like that.

And these are all important things, but it might be in the person sitting behind me in the pew who had a really bad week and just needs somebody to ask about it. Interestingly, there’s this woman who gets up at the corporate prayer request time. She’s recovering from breast cancer. And she always gives updates as the last person during prayer requests. And this time, she talked about how she joined a grief group because she goes, “As you guys know, I lost a dear friend a year ago. And the thing is, I know you all are here for me, but people get tired of you talking about this grief, but it’s still there.” And so she joined this grief group, and she talked about how she made this friend and just how helpful it’s been because they have each other to talk about their loss together still. And they don’t feel like they’re, like, burdening one another with it. And when we got home my husband was like, “that really made me think about you because you go through this major trauma, but people don’t want to hear about it all the time. You don’t talk about it.” And I write about it some, but as a normal person in everyday life, I’m not talking about it very much. And he’s like, “I just thought about what you’re still carrying.”

AQ: Hmm.

AB: And so it’s those little things in the community of God’s people, where I think the Holy Spirit’s working.

AQ: Yeah. That reminds me of the lines Kate Bowler talks about—and I can’t remember which one. But it says something like, “we can still talk about this a year from now or two years from now. I won’t ever get sick of hearing about this thing.” As being a sign of friendship in suffering. That struck me as so true. Like, am I willing to be like, “yeah, tell me about that divorce again, or tell me about that pregnancy loss again, even though it’s been 10 years?”

AB: Right. Diane Langberg talks about that too. That when we have big traumatic events, our brain can’t hold it. We can’t make sense of the narrative, and that’s why we have to say it so many times. We’re still wiring pathways to how this compartmentalizes into how I tell my story. And so we do need people in our lives that will let us repeat ourselves as we’re getting that story told.

AQ: Yeah, to make sense of the story that’s unfolding. You wrote Saving Face really as a first draft–or maybe second draft–of how that church experience is playing out in your story. But as your life goes on your story will change, and it’ll make different sense later.

AB: Yeah. So it’ll be interesting to revisit because, even now as I’m doing interviews, it’s been over a year since I wrote the book. And so re-reading, reading the audiobook, and now doing these interviews I’m feeling this connection with Aimee from a year ago. It’s so strange, but it’s giving me a different kind of hope, again, to see how I got through that and to see how God ministered to me through different people and all the beautiful parts and the pain.

AQ: You also do that with child Aimee in the book, like revisiting “spinning Aimee” in your first memory. You are practicing that in the writing, encountering your childhood self and trying to figure out what is the essential me and how is she still here? What parts am I hanging on to?

AB: Yeah. And even going back to some painful memories and wondering why that one’s being told the way that it’s told in my memory, being able to go back and revisit 14-year-old Aimee and her anger and her righteousness. You might have a lot of shame connected to a memory like that, but then to be able to say, you know what, I want to bless the parts that wanted attunement from your family. You wanted your parents to stay together. These are big things and good things that you wanted. I want to be able to bless those things. I think it rewires our brain. I mean, science is showing that now and so I was hoping by sharing those memories the way I did and doing kind of like that storied memory work that it would encourage not only the reader to do that, maybe in journaling, but to maybe start small groups and go and do those kinds of things. Because I think it’s even more powerful when we have witness and can share with other people. And it provokes something out of the listener as well.

AQ: Yeah, it’s interesting. When I was reading, and even hearing you talk, I know you have this interest in neuroscience as well. It sounds it’s very therapeutic. These are techniques from therapy. But you I didn’t mention therapy in the book. What is your thought on that? Even these small group tactics of storied memory, those are things a lot of people do like with a counselor, with a therapist.

AB: Right, right. Yeah, so I’m in therapy now. Finally, more consistently. But I’m also taking graduate level courses in in counseling, so I feel like going through this has definitely given me an interest. I’ve always had an interest in soul care and it got into my writing. Being more involved in the church and serving in the church and then having so many people come to me with their stories made me realize how much I would love to be able to be more helpful. And counseling is so adjacent to church work as they are both soul care.

AQ: Yeah, that’s a good way to put it. OK, this is a big question, but is this a book for an/ or about women? I’m thinking here that you do these extended interpretations–very original and interesting—from the Bible. Like the bronze basins in Exodus (Ex 38:8), or Serah, the daughter of Asher, or the woman from Song of Solomon. So, what do the women in the Scriptures have to say? And are you speaking to women in the book?

AB: I’m not speaking only to women. I mean, I definitely want to empower women with being able to take another look at what these sections in Scripture are telling us. Even in my book that got me in so much trouble– Recovering from Biblical Manhood and Womanhood–I spend the first third of that book looking at the male voice and the female voice in Scripture. So I’m really carrying a thread through of what I started there. And it’s just developed more.

I think it’s so important for men to see, too. I’m really enjoying some conversations that I’m having in interviews with men who are excited about this. If we can’t have that partnership and learn this together, I just think it’s going to be detrimental in the church. So not only for men to see how God is using the woman’s voice and just the unfolding of the symbolism of what we represent, but also the great need we’re seeing in the church of men to understand their masculinity in a more holistic way and to be able to embrace the “feminine” parts of that and their need for the feminine. I think that this could be one way to help with that.

AQ: Yeah, I love that. I hope that women are encouraged by it as well in seeing, you know, those voices and imagining what God is doing through the appearance of these female characters. Like, why are the women there in the tabernacle? They’re mentioned and I had never seen that. I had never thought about it before.

AB: Thank you. I know. Never heard a sermon on it. It blows your mind when you really start looking at it. And again, it’s more than just these propositional statements or teaching doctrine. There is a picture for us to uncover and discover. And I just think symbol speaks so powerfully, and it really does teach us. God uses symbol so much.

AQ: And again, an invitation to read with an eye for beauty and not for power.

AB: Yes, yes. And, you know, that takes training, too. Practice.

AQ: Yeah. And a soft heart willing to let the Bible speak instead of to impose some sort of systematic overtop of it, where this one verse becomes super-sized and all these other ones get completely put to the side. People tell on themselves when they do that.

AB: I know, I know. And you lose so much richness.

AQ: Yeah, I agree. Just one more really question. I would love to hear you talk a little bit about benediction, and the importance of benediction. What does it mean to be blessed by God’s countenance, and how do we how do we practice that?

AB: Yes. So I have up here on my desk Numbers 6:24-26. I know I grew up with that benediction sending us out of church every Sunday. It says: “The Lord bless you and keep you. The Lord make his face shine on you and be gracious to you. The Lord turn his face toward you and give you peace.”

And, you know, I’ve heard that so many times, but I never really thought about what it meant: the Lord’s face shine upon you. And interestingly, I really got into this philosopher Emmanuel Levinas. He really inspired the work in Saving Face. And he talks about the face as a metaphor. He talks about whether it’s even righteous to exist for you. But he concludes that yes, it is righteous to be because my face provokes you to be awakened to God’s blessing. And so it’s like this encounter. You’re being awakened to see the act of God awaken you.

So he talks about the naked face, and if we can get behind the countenance, our normal greetings and the mask we wear—”Yeah, I’m good. How are you?”–if we can have a true, genuine encounter and get behind that countenance, it’s really vulnerable, right? It’s kind of scary. That’s why we don’t do it. It leaves us exposed and vulnerable. You see that person’s vulnerability and their otherness, and it makes you realize your own otherness and strangeness. Levinas says that provokes the commandment in us “Thou shalt not kill.” Because you could liquidate that person, you know, once they’re vulnerable. We’ve all been on the receiving end of that liquidation as well. So we protect ourselves.

But I talk about the flip side of that being this call to bless, this call for us to notice that it’s good that you exist. And so when I think about this benediction, the Lord’s face shining on you, that provokes our longing for that great day when we have the beatific vision before the face of God in Jesus Christ. And we get to behold his face beholding us in delight. We imagine that gaze and our common longing for that. But I think that we get sent out with that benediction, not just for that day, but it’s actually a vocation.

You know, if Christ is in me, Christ is in my benediction to you, my greeting to you. My blessing you and saying that it’s good that you exist in my demeanor and in my whole posture towards you is a way of God’s face shining on you. And so I think that we’re supposed to be that now for one another, and that makes us come alive. That awakens us to love. It summons our own humanness, out of each other. So I think it’s extremely powerful just to truly greet somebody. We all know that, right? Don’t our hearts lift up when we know somebody’s glad to see us?

AQ: Yeah. Yeah, I love that. And it that feels like a very simple thing, but also something that’s so needed. I think that is true in the church. And it’s also true in our secular society where the image of God in individuals is so devalued. It’s all about commodification and how productive people are, how efficient people are.

AB: Exactly. And how much we know.

AQ: Yep. The question is are we falling in line? Instead of seeing people’s created goodness and the image of God in them, Christ in them.

AB: Great. And our otherness, you know, our otherness is a good thing. Levinas says that theology begins in the face of the neighbor because God descends in the face of our neighbor.

AQ: Hmm. Are there other ways that you think we can offer benediction other than being glad to see one another? How would you like to see people practice this?

AB: Yeah, I mean, I definitely think an easy and very powerful way is to show in your countenance that “it’s good that you exist. I’m glad that you’re here before me right now.” But, you mentioned, Kate Bowler. She has done a lot of work on blessing and, reading her work on that, I think is another way. Looking for God hiding throughout the day and practicing blessings, giving blessings, is a way. That’s benediction, right?

That’s benediction, practicing benediction.

AQ: Yeah. And I think too–and this is something that I’m working to do– recognizing that God is speaking. You talked about Barbara Brown Taylor saying we are stumbling, hitting our shins on all the altars. [“Earth is so thick with divine possibility that it is a wonder we can walk anywhere without cracking our shins on altars.”] Realizing if you get a glimpse of the sun it’s the Lord blessing you, encountering the world as reflecting God’s countenance, reflecting God’s blessings.

AB: You know, it’s funny because, I have spoken all over the place in front of a lot of people and have been pretty comfortable doing it, even though it was never an ambition of mine. But now I’m in this grad level class and having to give a presentation in front of 20 people and I’m one of the old people in the room. I walked in to do this presentation, and I was kind of nervous and I was like, “what in the world?” I’m nervous. You know, I’ve never done this before. But, you know, I just really prayed. I’m like, “Look, I want to find Christ in the room. Like in the little tiny things. Those little smiles, little blessings, little benedictions.

AQ: Yeah, winks of God. You quote someone saying that but I can’t remember who.

AB: Yeah, I can’t either.

AQ: Anne Lamont, probably.

AB: Probably.

AQ: Yeah, it was Anne Lamont. She’s talking about how as you get older, you have to just be OK with, like, ordinary days. But then you pay attention and you can see God winking at you all the time.

AB: Yeah, that’s it. You know, just looking.

AQ: Aimee, thank you so much for writing this book and sharing this time. Is there anything else you want to add or that you want readers of the Anxious Bench to know about you or about this work?

AB: No, I just thank you for your engaging questions and just engaging with my work, reading. I hope that it provokes some other thinking that I haven’t thought of yet.

AQ: Well, thank you. Thank you for your work and blessings upon you and your life.

AB: Thank you. Very kind. It was really good to talk to you.