I had the privilege of attending a conference in Rome on the Council of Nicaea about a month ago. Throughout the various plenaries, panels, and discussions, different historical and theological aspects of the council were explored in rigorous and exciting ways—it was a joy to be a part of! It was not until the final event of the conference that I felt we had truly gotten to the heart of Nicaea, though. The final event was a social, in which a group of university students sang the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed in Latin in the form of a worshipful prayer. This act did something that my own work presented at the conference did not—it reminded everyone that Nicaea is about worship.

I have been exploring different aspects of the council of Nicaea for its 1700th anniversary on the Anxious Bench for the last several months. This has included the investigation of the murky relationship between politics and theology and a discussion of several key (but often overlooked) figures from the council and Arian Controversy, namely Helena and Eustathius of Antioch. On this final post on the council, I wanted to discuss why the Council of Nicaea and its creed were so important for those attending the historical event. To the Nicenes, Nicaea was not ultimately about neat theological categories, political coercion, or winning a debate—it is about worshipping God properly, which includes thinking and speaking rightly of him. If this is the case, we too should consider the ways in which the Nicene Creed is formative for our own worship: it delineates the boundaries of orthodoxy and forms Christian identity.

The Boundaries of Orthodoxy

Worship of God is not only about heart posture, but also about proper belief. To misunderstand the object of our worship is to worship something other than the true God. In other words, orthodoxy must (at least in one dimension) be tied to proper understanding of God, and heresy is therefore derivation from suitable belief. Heresy is idolatry, insofar as it worships something other than the Christian God.

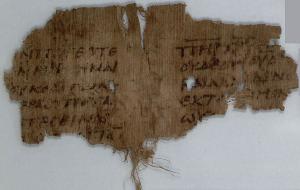

When the bishops gathered at Nicaea, one of the goals was to articulate an orthodox understanding of God and they accomplished this in a twofold manner through the creed. First, they developed the creed to summarize the basic beliefs of the Christian Church: the relationship of the Father to the Son, the salvific work of Christ, etc. Second, they expressed these core tenants in such a way that other views were excluded—namely, Arius’. That is to say, the bishops drew the boundary lines of orthodoxy in this document.

Of course, Arius believed the same about theology and worship and had his own boundaries, most fully discussed in a hymn he composed called the Thalia. Therein, he writes,

“God Himself – Insofar as He is – exists as ineffable to everyone. | He alone has no one equal to Him, no one like Him, no one with the same glory as Him. | We declare Him unbegotten on account of the begotten nature. | We praise Him as beginningless on account of the one who has a beginning. | We worship Him as eternal on account of the one who was born in time” (Arius, Thalia, from Fontes Nicaenae Synodi 18).

Arius’ framing is not one of abstracted theological ideas, but of a posture of worship towards God. But unlike Nicaea, Arius’ praise of God the Father is due to his transcendence over the Son of God, who is a perfect creature (For discussion, see: Anatolios, Retrieving Nicaea, 42-52). In other words, Arius’ theology means that Christian worship is oriented to the Father and not the Son. In fact, the Son himself “praises the Greater one (Father) partially”, insofar as he is unable to fully know the Father’s essence (Arius, Thalia). In sum, rival theologies lead to rival forms of worship, which is seen in competing hymns and liturgies between Nicene and Non-Nicene communities throughout the fourth century (Vaggione, Eunomius of Cyzicus and the Nicene Revolution).

Such divergence of opinion raises the question for the Nicenes and for us: what are the proper boundary markers for worship in the Church? For around 1650 years, Nicaea has been the standard articulation of

trinitarian orthodoxy for the church, with the creed being used in worship regularly from at least the sixth century onwards. In other words, the majority of Christians have affirmed that Nicaea describes who the Christian God is. But recent trends demonstrate that a Nicene understanding of God is quickly being forgotten. A survey in 2022 seemed to indicate that up to 53% of Christians and 27% of evangelicals in the US agree or somewhat agree with the statement that “Jesus was a great teacher, but he was not God.” Even Arius would disagree with this and he is closer to the Scriptures in claiming the Son “is the Only-begotten God” (Arius, Thalia, FNS 18), even if he is a creature!

One must wonder whether regularly reciting the Nicene Creed has historically been formative for preventing this sort of grave misunderstanding of Christ’s divinity, especially in the affirmation that the Son is “God from God, Light from Light, true God from true God.” By regularly articulating the Creed in worship services, one is reminded of the boundaries of Christian orthodoxy, which means our worship is oriented to the God of the Scriptures. The Creed is meant to articulate that the God of the Christian church is this God, and we need regular reminders of the object of our worship amidst our prayers and praises.

Identity Formation

The Nicene Creed is not only formative in our conceptions of God, but in our conceptions of the Christian church. And this is not just in the clause from the Nicene-Constantinopolitan creed “[We believe] in one holy universal and apostolic Church” (which is not in the creed at Nicaea in 325!). The recitation of the Nicene Creed—in its original affirmation and in churches today, confirms Christian community.

There were Christians represented from across the Christian world at the council of Nicaea, though the majority were from the Christian east. In this gathering, there is great theological, doxological, and socio-political diversity. We might wonder what holds together John of Persia, Alexander of Alexandria, and Ossius of Cordoba, bishops from Persia/India, Egypt, and Spain respectively. As it turns out, the theological proclamations of the creed are that which binds them together. Every bishop in attendance signs it, affirming the core of the Christian faith.

We need to remember the center of Christianity now more than ever. The Christian church is a splintered one—whether you consider fracturing denominations in Protestantism, strife and division amidst Roman Catholics, and contending conceptions of Christianity amidst Orthodox Christians across the world. The creed of Nicaea reminds us of something important: we are united around the core of the Christian faith, that is God and his work for our salvation. In this, there is formative power in regularly reciting the Creed in a local and an international community, as it reminds Christians of their ecclesiastical unity amidst confessional emphases. To recite the creed together, is to provide an embodied experience of unity.

In our investigations into the Council of Nicaea and its creed, might we remember the proper context of the creed—the church. This document is not a collection of abstract ideas floating free from the lived reality of the Christian, but one which grounds our worship insofar as it teaches us about who God is and who we are as a church. Might we all, with one voice, declare: “We believe…”