Lynneth Miller Renberg’s discussion of archival silences and archival shouting in Listening to Archival Silence: History and Hidden Voices last month started me thinking about how we extract information from the archives. We can’t find what’s not there of course, but even when materials are present, finding them depends on how or whether they’ve been categorized, per the example of Sor Juana de la Cruz in the Karin Wulf article Renberg cites. Various factors affect archival research, like institutional collecting habits, cataloging systems, preservation structures, priorities, etc, resulting in archival silences, i.e., absent or occluded histories, or archival shouting, i.e., emphasizing certain materials over others. As Renberg notes: “The challenge of the historian is to amplify the voices that are silenced (or just not preserved at all) while bringing the shouted voices back to a proportionate volume. Only in a rightly balanced chorus of voices do we clearly see and understand the past, both its events and what it was like to live in it.”

I’ve begun a new writing project that will, I believe, contribute towards balancing the archival chorus. It’s historical fiction, but unlike my most recent project – a children’s chapter book about a sixteenth-century Nahua-Christian man living in what became New Spain – this novel for adults focuses on a sixteenth-century Castilian-Christian woman who emigrated to New Spain. The name of this Castellana is María de la Paz; I found her story spread across hundreds of folios in archives in Mexico and Spain.

Writing historical fiction is a complex process. Michael Jimenez’s recent post, Min Jin Lee and the Art of Historical Fiction – in which he discusses his use of historical fiction in the classroom, something I discussed last year in Teaching Latin American History via Historical Fiction – provides a useful exploration of two methods of writing historical fiction. The titular author of Jimenez’s post, Min Jin Lee, takes a journalistic approach, spending years researching, compiling notes, and writing. Jimenez compares her to Vanessa Chan, who in It’s Time to Rewrite the Rules of Historical Fiction beautifully describes how her first novel, The Storm We Made, emerged from the internalized memories her grandmother had told her about surviving the Japanese Occupation of Malaysia during WWII. Chan argues that memories are records and that “the power of fiction is its ability to transcend the wobbliness of facts—to write shaky moments into concrete evidence and make them studier than historical event.” I love that. I’ve taught memory projects in history courses and I have my own family memory project that I’ll describe another time.

My approach to this work of historical fiction is unlike the two mentioned above, as the original iteration of this project was a scholarly monograph.

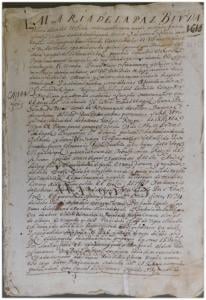

Last Will and Testament of María de la Paz (14 April 1614) & Amendments (21 April 1614) [Fondo Real de Cholula, Archivo Histórico Judicial de Puebla (AHJP), Puebla de los Ángeles, México, 133v. 311v-370r. Cuaderno 8 (118 fojas)]. Photo by author.

I “met” María de la Paz quite by accident. In the archives during my first research summer in Mexico as a doctoral student at UCLA, I was searching notarial records for clues about the early sixteenth-century development of my subject town, Cholula, but the earliest records I found were from the 1590s. María de la Paz appeared in a batch of 23 wills that I photocopied. Noticing her name again and again, I photocopied the other documents in which she appeared, but set them aside to focus on my dissertation.

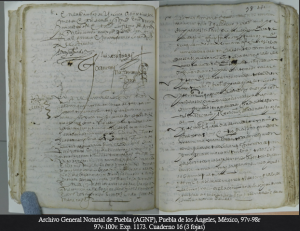

Even so, María de la Paz remained on my mind. Apparently, while living in Cholula in the 1590s she had become a successful obrajera (female textile mill owner) after her first husband died, buying and selling land and employing many native people in the process. She was even imprisoned briefly with a group of other obrajeros for locking her native workers inside the textile mill at night (a common practice, unfortunately), but reappeared in the historical record a few days later. She became gravely ill in 1595, and the will she dictated (she was illiterate) provides a useful list of her debts and assets as well as the name of her late husband and the names and birthplace of her parents in Castile, information that could help me locate details about her early life in local archives in Spain.

Last Will and Testament of María de la Paz (23 October 1595). [Archivo General Notarial de Puebla (AGNP), Puebla de los Ángeles, México, 97v-100v. Exp. 1173. Cuaderno 16 (3 fojas)]. Image captured by author.

Last Will and Testament of María de la Paz (23 October 1595). [Archivo General Notarial de Puebla (AGNP), Puebla de los Ángeles, México, 97v-100v. Exp. 1173. Cuaderno 16 (3 fojas)]. Image captured by author.

When I presented my preliminary research at a conference in Oaxaca in 2018, a scholar recognized María de la Paz’s name from another archive, leading me to documents that illuminate her final days in Cholula. In a sealed will, she named her second husband and designated a surprising universal heir – a son she had left behind in Castile (and had not claimed in her 1595 will). Who was he? None other than the Inquisitor General of Castile(!). When Cholula’s highest-ranking official, the corregidor, unsealed her will to appease her creditors and thus unlocked her secret, María de la Paz died of shame. Quite a story, right?

While reading Ida Altman’s compelling Translatlantic Ties in the Spanish Empire: Brihuega, Spain, and Puebla, Mexico, 1560-1620, I discovered that in 1573 María de la Paz had accused a powerful textile baron and member of the town council of Puebla de los Ángeles of bigamy, launching a Inquisitorial investigation. A two-decade resident of Puebla at the time, she soon appeared in the documents as a resident of the nearby indigenous city of Cholula. Was she driven out of Puebla for defaming the powerful? Perhaps. She says her confessor refused her absolution unless she brought this charge before the Inquisition, but did she deliberately confess the religious crime of her rival to procure a layer of protection from the Church, knowing the priest would force her hand?

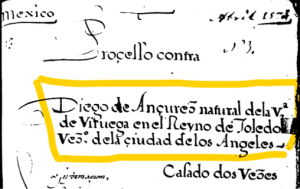

Bigamy case against Diego de Anzures, native of Brihuega, citizen of Puebla de los Ángeles, 1573 [Archivo General del la Nación, Inquisicion, Vol. 101, exp. 3]. PDF image captured by author.

During my sabbatical in 2019-2020, I shared my developing research at a conference in Cholula. Members of the town council attended my presentation and the women were intrigued to hear about the success of a woman in Cholula at a time when women were barred from sitting on the town council. Then Covid hit. Between losing my sabbatical, leaving my faculty position, homeschooling, launching a Spanish Great Books Program online, and writing my first book of historical fiction (currently under review), my María de la Paz project stayed on the shelf.

Not anymore. Inspired by Isabel Allende’s Inés of my Soul and Elizabeth Borton de Treviño’s Newbery-medal winning I, Juan de Pareja, I’ve decided to write María de la Paz’s story as first-person historical novel, filling in the gaps in the archival record with historically appropriate narrative.

I’m not shifting to historical fiction because it’s easier than historical scholarship, because it certainly isn’t. As my students know, sometimes ensuring the accuracy of a historical detail – how a character would greet someone or what a character would wear, for example – might require hours of research. Nor am I shifting to historical fiction because it has exploded in popularity, as noted in this Esquire article, The Mainstreaming of Historical Fiction.

I’m writing a first-person narrative because I want to fully engage with my protagonist, to understand her, to immerse myself in her experiences, to see the world she saw. As Vanessa Chan notes, “Good historical fiction feels immersive. Despite the strangeness of the times, you, the reader, feel as though you are seeing the world through your narrator’s eyes…it’s about the ability to become engulfed in the ‘story’ part of history, to feel the emotion and stakes of the moment, even if time has passed.”

María de la Paz’s story deserves to be told, but more than that, she deserves to be known, to have her voice extrapolated from the hum of voices in the archive, to be seen and heard, silent no more.