As our guide walked with us out of the Hagia Sophia in Istanbul, he started telling us about the planned restoration to the famous church and mosque, set to start this year. “The biggest challenge has been deciding to what century they’re restoring each part,” he said. For the Hagia Sophia (and so many other sites), that’s a rather politically and religiously fraught decision. Would a faithful restoration focus on the site’s first design and structure, from its construction as a church by Justinian I in the 6th century, with its emphasis on geometric patterns, fruit, and crosses? Fire and earthquake damage, along with expansions done by the Byzantine emperors who followed Justinian, mean that no restoration can bring the space back to its 6th century appearance– any restoration is going to be reliant on later additions.

Since going back to the original church (whether Justinian’s or the first church on the site, built two centuries before his and destroyed by fire) isn’t possible, should a restoration focus on the later Byzantine mosaics and frescos that defined the space in the 11th-14th centuries, depicting in gilt and bright colors figures from scripture and Byzantine rulers? Many of these do survive, as we know from a 19th-century restoration project. As a medievalist, I’d certainly like to see these mosaics and frescoes– but if that is the focus of a restoration, what to do with the early modern frescoes crafted by the Ottoman emperors? These frescoes, added almost 1000 years after the construction of today’s building but still almost 600 years old, are both beautiful and historically significant in their own right, and with their geometric designs and focus on fruits and patterns, in some ways are closer to Justinian’s original design despite being from a different religious tradition.

No matter what choices the preservationists make, the restored Hagia Sophia won’t be like any of its past versions. Those can’t be fully recreated. So how do we make good decisions here? When restoring things, particularly layered spaces or traditions, how do we decide what the ‘original’ we’re seeking to preserve is?

Places as Palimpsests

I walked away from that tour thinking about the Hagia Sophia like a medieval manuscript– a palimpsest, to be precise. It’s not a common term, but one that points us towards a fascinating aspect of the study of medieval manuscripts: they often hide invisible texts, much like invisible ink.

Palimpsests are manuscripts that have layers of use, which creates layers of text. Vellum (also called parchment), the animal hide that many manuscripts are made from, was extremely expensive and difficult to create. For example, producing a complete Bible on parchment would require the use of over 200 sheep! Thus, it was common practice in the Middle Ages to recycle (or “rescratch”, the origins for the term palimpsest) papyrus or vellum pages when the texts originally written on them were seen as unneeded (or perhaps banned).

For papyrus, the process was a bit simpler: flip the page over and write on the side that was less easily inscribed. Many parchment texts have the “important” information on the front and the “unimportant” information on the back, creating a treasure trove of records that would have otherwise been thrown away.

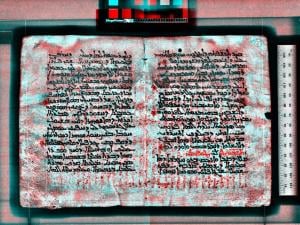

For parchment texts, the process was a bit more involved. It was possible to scrape the ink from a vellum page, leaving it (fairly) clean and ready for a new text. And that’s exactly what scribes did, removing writings that they considered no longer useful and adding texts that reflected their priorities and beliefs on the newly blank page. Sometimes the scraping process left behind legible traces of the first manuscript, making it possible to read both texts at once (albeit not easily). Other times, the first manuscript disappeared entirely, only visible using multispectral imaging or other technologies. It’s using this sort of technology that has allowed us to find exciting new connections between parts of the medieval world, like in a double palimpsest from Egypt (a text with three layers of writing) that contains, according to the British Library, “commentary on Donatus’s Latin grammar attributed to Sergius from the 7th century, written above another 5th-century Latin text preserving fragments of the otherwise lost historical work of the 2nd-century Granius Licinianus, whose writing is known only from these recycled pages.”

Sites like the Hagia Sophia present us with similar challenges to these manuscripts: we can’t view all the layers at once, and there might be exciting new discoveries underneath the later additions. But the latter texts (or frescoes or art) are also historically significant, with much to tell us about the past. The tension is in preserving all of the layers at once, so that we can create as much of a historical record as possible for future generations, who may have new technologies and new ways of seeing and understanding the sources that are not currently available to us. Victorian scholars could not have dreamed what was hidden under the Latin in some of the medieval palimpsests we now know about– and who knows what we’ll find as technology continues to develop.

Church History as Palimpsest

So far, this has been a rather long tangent into the nerdy weeds of medieval manuscript studies and historic preservation. But what does this all have to do with church history?

In a conversation with a friend about the history of the church’s approach to sacraments and corporate worship, it struck me that much of church history is also like a palimpsest. We’re likely all familiar with the push towards recreating the practices of the early church in our ecclesiastical practices. Francis of Assisi and the mendicant movement of the Middle Ages argued for a return to apostolic poverty; Martin Luther and the reformers of the early modern period argued for reforms that would remove what they saw as later additions to doctrine and for a return to models of sacraments, authority, and faith drawn directly from scripture; nineteenth-century reformers in the Stone-Campbell movement (also called the Restoration Movement) argued for a return to New Testament practices of communion, baptism, and the abolishment of denominations in the name of unity– the list could go on.

In short, almost every era of church history has wanted to restore original practices and theology. And yet, what exactly is being restored has looked wildly different across these movements. Part of this is because the question of what exactly is the original is so unclear. The New Testament contains a few brief verses describing the practice of the earliest churches in Acts 2:42-47:

“42 They devoted themselves to the apostles’ teaching and to fellowship, to the breaking of bread and to prayer.43 Everyone was filled with awe at the many wonders and signs performed by the apostles. 44 All the believers were together and had everything in common. 45 They sold property and possessions to give to anyone who had need.46 Every day they continued to meet together in the temple courts. They broke bread in their homes and ate together with glad and sincere hearts, 47 praising God and enjoying the favor of all the people. And the Lord added to their number daily those who were being saved.”

From this, it’s clear that the earliest churches met together, learned together, prayed together, and ate together- but it’s not clear exactly what the practices of communion or baptism looked like, whether in practice or in frequency (although we get some clues in the Didache). The account of the Last Supper, in Matthew 26:17-30, provides a liturgical script for communion, but clearly not one we can replicate exactly, as Christ incarnate does not stand in our churches and administer his body and bread himself. From these specific yet broad and vague details, centuries of debate about church tradition and rightly ordered practice (orthopraxis) have emerged, with each movement convinced their understanding of the source material is the original one.

Palimpsests and Practices

This is where the techniques for reading a palimpsest might be helpful to us, not just in reading manuscripts or historic sites but in thinking about church practices.

First, I think there’s value in recognizing that what we have when we try to understand orthopraxy using church history as a guide is a palimpsest: layers of cultural understandings, worked out in church practice, with each layered text (each historical period) containing something of theological value. Our own movements use technologies of interpretation (the priorities and values of our own culture and society) to read the manuscript of orthopraxy and arrive at our conclusions- and we’d do well to not see the layer we can read as the final word.

Second, as medieval scholars will tell you, each layer of a palimpsest has valuable meaning. 10th century authors might have seen the 5th century texts as useless, but 21st century authors learn entirely new things from them, things that add innumerably to rightly ordered understandings of the past. Likewise, while we may not agree with every past era’s approach to orthopraxy and tradition, we can learn theological truths from the layers that came before us– but we have to study these past practices in order to do so.

Finally, I think that in recognizing that restoration to the “original” of church history isn’t possible, a greater spirit of ecumenicism is possible. No church tradition today exactly replicates the practices of the apostolic church– and it’s not possible for any church to do so. Yet, in any church tradition that seeks to follow orthodoxy and orthopraxy, taking the New Testament texts seriously as guides to communal living, to worship, and to church discipline, we can see layers of theological meaning. What do we do with a palimpsest, whether a historic site or an approach to sacraments? We learn from each of the layers, trying to preserve and understand each one.