This post grows out of my recent work on the huge vogue in late nineteenth century America for predicting the near future – for utopian and (broadly) science fiction literature. As people projected that future, with its startling technology, they commonly predicted the growth of what we can call human superpowers, which were occult in nature as much as scientific. Through my research on that era, I keep encountering these themes. Originally, this is something I dismissed as the quirk of a couple of isolated thinkers, but increasingly I see a pattern, and one that I think is a real force in the religious thought of the day. Briefly, when we look at the history of ideas of healing, magic, and miracle, we must always remember that some very well-informed people in that fairly modern era interpreted such acts not as supernatural but as the outcome of material, physical laws that science had not yet learned to understand fully. Spiritual powers were actually rooted in science, albeit a science that we had not yet fully comprehended. And as they thought about the near future, they assumed that these forces, these powers, were destined to be recognized ever more widely, and viewed in scientific terms.

Once you understand that perception, you begin seeing it all over the place – in discussions of revivals and healing movements past and present, and of Biblical studies. You soon realize that this is no mere quirk, but a really influential way of interpreting spiritual claims, and spiritual realities.

To be clear, this is different from the other very potent idea of that era, the New Thought or Mind Cure claim that the power of the enlightened mind could end one’s own sicknesses, physical as well as mental. The physical powers I am describing certainly overlap with that principle, but they are a separate thing.

I sketch this idea briefly here, but let me just introduce the theme for discussion.

Certain Natural, But Generally Unknown Laws

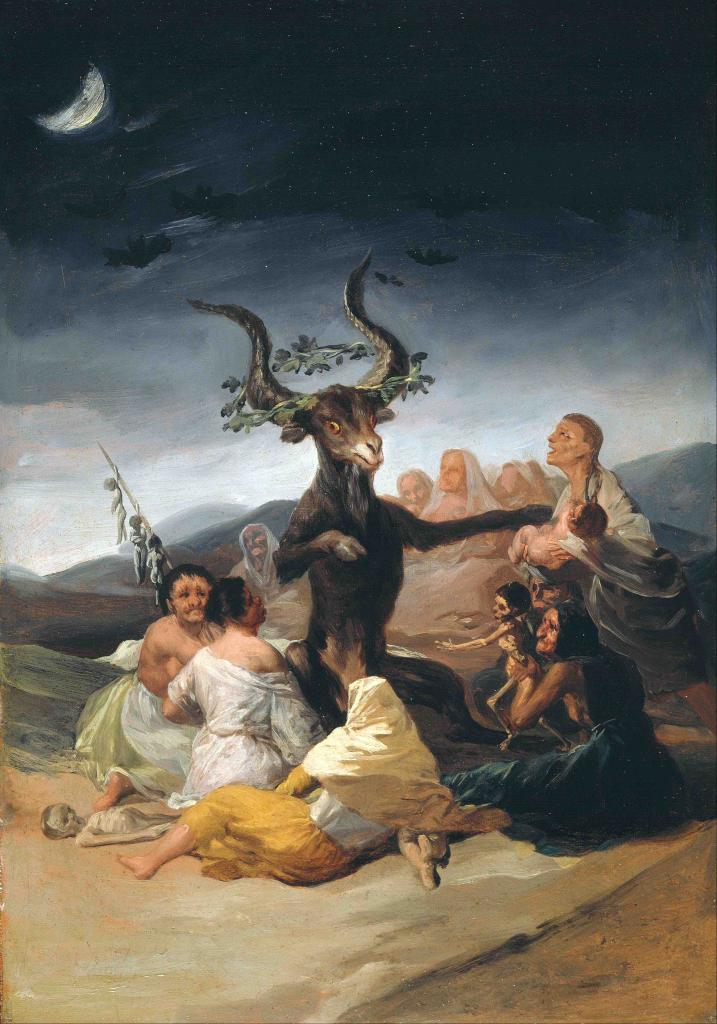

I recently wrote about the important American reformer and Theosophist Matilda Joslyn Gage, and her groundbreaking work on women’s spirituality, Woman, Church and State. She has a sizable and significant account of witchcraft, which she presents as an actual historical movement, rather than as just the fantasy of heresy hunters and witch-finders. Witches, covens and sabbats all existed.

On close examination, she says, women were totally innocent of the harmful crimes of which they are accused, but that does not mean that there was no basis to the male-driven persecutions. If accused women were not actually carrying out curses or malevolent witchcraft, they really did possess scientifically-based psychic powers that we might call forms of ESP. To support the idea, Gage cites the work of the Italian scientist Filippo Pacini, who in the 1840s had identified receptors in the nervous system, the “Pacinian corpuscles”. These are concentrated in certain areas of the body, and “This apparatus—almost formed like a voltaic pile, is the instrument for that peculiar vital energy, known more or less to all students as Animal Magnetism.” That term takes us back to Mesmerism, which had exercised such astonishing appeal in the US earlier in the century, but which now, seemingly, acquired a new physiological basis.

all images here are in the public domain

all images here are in the public domain

Some individuals had the power to control these areas of high sensitivity and magnetism to create effects that would otherwise be described as magical.

A vast amount of evidence exists, to show that the word “witch” formerly signified a woman of superior knowledge. Many of the persons called witches doubtless possessed a super-abundance of the Pacinian corpuscles in hands and feet, enabling them to swim when cast into water bound, to rise in the air against the ordinary action of gravity, to heal by a touch, and in some instances to sink into a condition of catalepsy, perfectly unconscious of torture when applied.

The more we understood of electricity and magnetism as they affected the human body, the better able we would be to read the historical record, and to deploy those powers for ourselves. These were the lessons taught by “Galvani, Pacini, and those more recently connected with electricity, notably of Edison and Nikolas Tesla.”

She drew heavily on the work of the German Dr. Justinus Kerner, who in the 1820s had examined a clairvoyant and dreamer prophet called The Seeress of Prevorst, and had written a credulous account of the case, which emphasized those “magnetic” elements. The US edition (1845) bore the sensational title The Seeress Of Prevorst; Being Revelations Concerning The Inner-Life Of Man, And The Inter-Diffusion Of A World Of Spirits In The One We Inhabit. Gage treated every word, every claim, as authentic and as hard science.

In short, said Gage,

Magic simply means knowledge of the effect of certain natural, but generally unknown laws; …consequences resulting from control of the invisible powers of nature, such as are shown in the electrical appliances of the day, which a few centuries since would have been termed witchcraft.

Magic, Science And Mind-Power

People commonly use the advanced technology of the day as an analogy to understand magical or mystical phenomena. In the 1840s, for instance, observers of Spiritualism regularly drew comparisons with the telegraph. The amazing growth of electricity at the end of the century naturally encouraged thinkers like Joslyn Gage to offer pseudo-scientific explanations for those other occult manifestations.

Curiosity about such things led in 1882 to the formation of the (British) Society for Psychical Research, which sought to apply scientific methods to such matters as apparitions, hypnotism, hauntings, thought transference, mediumship, and seances – and also telepathy, a word coined in 1882 by a member of the Society itself. Over the next quarter century, the Society engaged in many highly publicized studies, which promoted belief in a possible scientific basis for such phenomena. The American Society for Psychical Research dates to 1884.

By the way, the phrase extra-sensory perception was coined by Sir Richard Burton in 1870, although it was not popularized until the 1930s. Parapsychology dates from 1889.

Esoteric Christianity

Matilda Joslyn Gage, then, was anything but unusual in her theorizing. Very similar views regularly appear across the intellectual spectrum, from esoteric and Theosophical thinkers to quite mainstream religious believers. Another celebrated Theosophist and feminist was Annie Besant, who in 1902 published her account of Esoteric Christianity. Much of her material assumed the material force of supernatural power, specifically located in the body’s own magnetic qualities. The “vital magnetism” of a holy person magnetized nearby bodies, and that caused the phenomena we know as healing or holiness. Jesus himself “healed many a disease by word or touch, reinforcing the magnetic energies belonging to His pure body with the compelling force of His inner life.”

This is the secret of magnetic cures: the irregular vibrations of the diseased person are so worked on as to accord with the regular vibrations of the healthy operator, as definitely as an irregularly swinging object may be made to swing regularly by repeated and timed blows. …Magnetic changes are caused in the ether of the physical substance, and the subtle counterparts are affected according to the knowledge, purity, and devotion of the celebrant who magnetises–or, in the religious term, consecrates–it.

The Spiritual Unrest

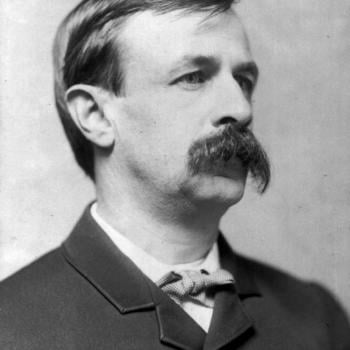

As I can say, we can readily dismiss Besant and the rest as idiosyncratic (or worse), but such ideas really did have a phenomenal appeal. In 1910, for instance, the influential social commentator Ray Stannard Baker published a best-selling survey of contemporary American religion called The Spiritual Unrest. The book’s epigraph quotes William James writing in 1907, and proclaiming that “It is quite obvious that a wave of religious activity, analogous in some respects to the spread of early Christianity, Buddhism, and Mohammedanism, is passing over our American world.” And what was that Unrest, that epochal spiritual revolution? It certainly included New Thought, Christian Science, spiritual healing, and spiritualism, but it was much larger in scope. As Baker wrote, the great force in modern spirituality was “the new idealism”:

The new idealism lays its emphasis upon the power of mind over matter, the supremacy of spirit. Its thinkers have interested themselves as never before in the marvelous phenomena of human personality, most of which were contemptuously regarded by the old materialistic science. The wonders of the human mind, the attribute we call consciousness, the self, the relation of mind to mind, telepathy, the strange phenomena of double or multiple consciousness, hypnotism, and all the related marvels, are now crowding for serious attention and promise to open to us new worlds of human knowledge.

Telepathy, hypnotism, the mystic powers of the mind… and in each case, treated not as mystical or supernatural powers, but as thoroughly natural and material, lying in wait to be discovered once science deigned to examine such claims.

William James himself reported such claims extensively, even if he did not believe them literally. But even he noted the prodigious expansion of what had once been considered magical powers once they were framed in psychological terms. And as he noted, psychological phenomena might have observable effects on bodily reality. This is from his Varieties of Religious Experience (1902):

Miraculous healings have always been part of the supernaturalist stock in trade, and have always been dismissed by the scientist as figments of the imagination. But the scientist’s tardy education in the facts of hypnotism has recently given him an apperceiving mass for phenomena of this order, and he consequently now allows that the healings may exist, provided you expressly call them effects of “suggestion.” Even the stigmata of the cross on Saint Francis’s hands and feet may on these terms not be a fable. Similarly, the time‐honored phenomenon of diabolical possession is on the point of being admitted by the scientist as a fact, now that he has the name of “hystero‐demonopathy” by which to apperceive it. No one can foresee just how far this legitimation of occultist phenomena under newly found scientist titles may proceed—even “prophecy,” even “levitation,” might creep into the pale.

Might even those lurid phenomena be psychosomatic? Levitation??

“The Thoughtful Attention Of Psychical Researchers”

Theosophy and the esoteric groups rendered their greatest service to spreading the new ideas not by any deliberate pamphleteering or advocacy, but rather by creating the technical language and theoretical structure that gave them an apparent scientific basis. Once the word clairvoyance (for instance) was established in popular discourse, the implication was that the phenomenon was authentic, that it was A Thing, and one that educated people needed to know about.

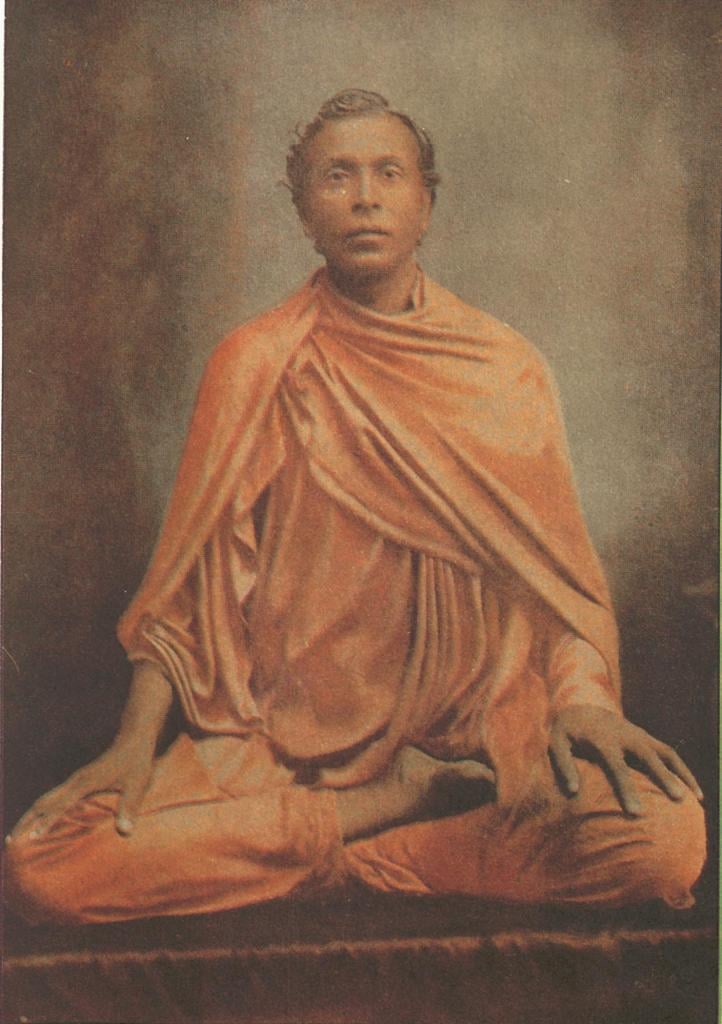

This was illustrated at the World’s Parliament of Religions held in Chicago in 1893. One of the South Asian speakers who made an immense impact was the Ceylonese Buddhist reformer Dharmapala, who summarized his faith for his American hearers. He spoke of the Buddhist path to enlightenment and liberation, and declared that

Thought transference, thought reading, clairaudience, clairvoyance, projection of the subconscious self, and all the higher branches of psychical science that first now engage the thoughtful attention of psychical researchers are within the reach of him who fulfills all righteousness, who is devoted to solitude and to contemplation.

Although he might well have been representing traditional Buddhist opinions, almost every word here betrays the influence of his Western mentors and translators, who were leading Theosophists. That background was not apparent to his Chicago audience, who assumed that they were receiving the pristine voice of Asian religious truth – and how impressive that it yet again reinforced Theosophical claims!

Fiction, Horror Tales, and the Frontiers of Science

Popular fiction supplied another vehicle for disseminating such claims, and the attendant technical language. This mattered greatly because such productions reached mass audiences far beyond the readership for esoteric or pseudo-scientific publications.

The early twentieth century was a great age for horror and supernatural fiction, with all the predictable themes of ghosts, hauntings, devil-cults, and demons. When you immerse yourself in this world, you find just how often these authors presented such evils not as supernatural, but as avant-garde scientific practice. Like Joslyn Gage, these writings regularly posited a scientific basis for claims about witchcraft.

I will only offer a couple of examples here. In 1915, the occultist J. W. Brodie-Innes published the sweeping novel The Devil’s Mistress based on the seventeenth century Scottish witch Isobel Gowdie, whom he presents as a natural healer with genuine clairvoyant powers. The author suggests just how the witnesses to such historic events could have described the fantastic things they reported so regularly:

Later authorities, aware of the strange hallucinations produced by what is now called hypnotism, have thought that the Dark Master, whatever else he might have been, was a powerful hypnotist and was able by these means to produce in the whole congregation the illusion that they actually saw Mistress Isabel sitting in the kirk beside John Gilbert.

As Brodie-Innes suggests,

The recovery of many of the incidents in the tale, and their subsequent confirmation by documents, and much concerning the writing of the book itself, would form exceedingly interesting matter for the Society for Psychical Research.

In 1927, the famous literary critic Herbert Gorman published his folk horror novel The Place Called Dagon, which imagined a witch cult operating in modern day New England. He argues that the original Salem witches

belonged to a secret and blasphemous order that met all over the world, that they were divided into covens or parishes, that they each had their leader in the shape of a Black Man who represented the devil, and that they attempted to practice magic…. The trappings and the ceremonies and the results might appear supernatural, but that was because the people in those days did not know about such things as thought-transference, auto-suggestion and the impulsion of the will.

Around the same time, John Buchan’s story “Ho! The Merry Masons” suggested that sinister forces might reside in ancient houses where sinister cults had practiced evil rituals. He rooted his hauntings in what might be seen as a scientific theory, as a character speculated that moments of extreme strain or emotion could literally leave traces in the environment:

‘It needn’t be only in the air,’ he said. ‘Why should it not be in the whole physical environment – stones, trees, a glen, a hillside? We do not know what queer intricate effects the human soul may have on inanimate things. A physical environment may be charged with psychical stuff as a battery is charged with electricity, and, when the right conductor appears there may be the deuce to pay.’

Miracle, Science, and the Middle Ground

The new insights were wonderful news for horror writers, but they also had a surprising resonance for serious observers of religion.

When a modern writer examines the miracles of Jesus, or any holy figure of the past, a number of possible interpretations offer themselves. Perhaps the miracles actually occurred as described, through supernatural means. Perhaps they never happened as objective realities, rather than as symbolic events or Signs. But in earlier times, another possibility presented itself, namely that Jesus really did perform cures by means of deploying those powers that superstitious ages misunderstood as supernatural or demonic. In the intellectual climate of the age, such a possibility seemed not only permissible, but probable. Even if the miracles had occurred, that said nothing necessary about Jesus’s divine or supernatural status.

The vital issue was that observers and historians did not have to choose between natural and supernatural explanations of such wonders. A whole middle area existed, one that, while based in Nature, actually seemed to be supernatural.

To take one example of many expressing this idea, I quote Charles Augustus Briggs, America’s best known exponent of Biblical Higher Criticism, speaking at the World’s Parliament of Religions in 1893. Although Briggs himself did not hold such reductionist opinions, he was well aware of critics who did. As he remarked,

If it were possible to resolve all the miracles of the Old Testament into extraordinary acts of Divine Providence, using the forces and forms of nature in accordance with the laws of nature ; and if we could explain all the miracles of Jesus, His unique authority over man and over nature, from His use of mind cure, or hypnotism, or any other occult power, — still I claim that nothing essential would be lost from the miracles of the Bible ; they would still-remain the most wonderful exhibition of loving purpose and redemptive acts of God and of the tenderness and grace of the Messiah’s heart.

The use of technical “mind-cure” terminology here is striking, suggesting the larger thought world of New Thought.

Nor need such powers have vanished with the passage of time. If you believed in those forces – which actually derived from hitherto misunderstood zones of authentic science – then that night account for the healings so widely claimed in revivals. The Pentecostal upsurge following 1906 was an obvious case study, and that attracted true believers in all sorts of marginal science.

At Azusa Street, evangelist William Seymour was repeatedly troubled by mediums and occultists who used Pentecostal services as a setting for seances. Charles Fox Parham was shocked to see “the manifestations of the flesh, spiritualistic controls, [and] saw people practicing hypnotism at the altar over candidates seeking the baptism.” Critics of that revival (and others) often flung charges that such sinister powers were being used so freely to create a veneer of credulous faith.

As I say, I am only here scratching the surface of a significant cultural motif. As you read the original records of such movements from that era, and the interpretations of earlier eras, do be aware of that cultural background.