The Brexit vote, the attacks in Nice, and the attempted coup in Turkey have a made it a rocky period for Europe. The example of Brexit and the Nice attacks (which brings to 242 French deaths by terrorism this year), in particular, betoken the further destabilization of the European Union and raise questions about its long-term viability. While rumors of its death have been exaggerated by some, it merits remembering that one need not go back to Babylon or Rome to reflect on disintegrated political entities. There is a recent example in Europe’s backyard: Yugoslavia (1918-1992).

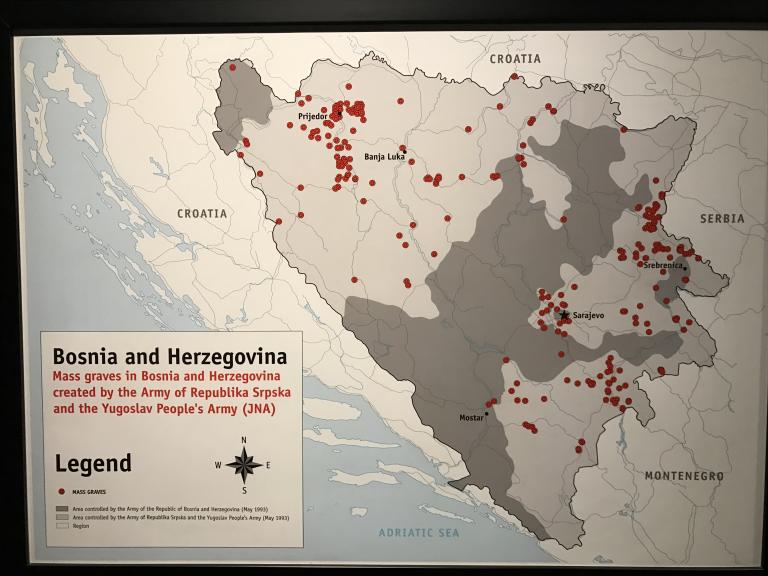

An improbable creation, Yugoslavia was stitched together in the aftermath of World War I from Balkan regions formerly in the Austro-Hungarian or Ottoman Empires. The country survived World War II (barely), but later fell apart due to the furies of nationalism and their attendant conflicts unleashed after 1989.

Tamping down religious divisions was always necessary for its survival, for the Balkans contain the combustible fault lines where Eastern Orthodoxy, Latin Catholicism, and Islam come together—the latter representing the remnants of the Ottoman Empire and are ensconced especially in Bosnia-Herzegovina and Kosovo. It took the strongman Josip Broz Tito to make it all work in the postwar period. But his death in 1980 heralded the beginning of the end. In the final analysis, too many divergent interests, bitter memories and old hatreds made Yugoslavia viable as a state.

I have been thinking about Yugoslavia recently from reading two classic books on the Balkans: Rebecca West’s Black Lamb and Grey Falcon: A Journey through Yugoslavia, an absorbing travelogue-cum-meditation-on-historical-forces based on the author’s travels to the region in the late 1930s, and Robert D. Kaplan’s Balkan Ghosts: A Journey Through History, based on his own travels there in the 1980s and 1990s. I highly recommend both books. But do budget time: the Penguin edition of West’s book runs to 1150 pages!

Historical comparisons always beg questions. But at least three similarities between the EU and Yugoslavia merit mentioning. First, both represent elite political constructions that too often failed to take into consideration views from “below,” from the governed. Second, both represent attempts to paper over longstanding divisions and patterns of mistrust among various regions, trusting that economic and political manipulations alone can work such magic. Finally, given their fragile, constructed nature both were/are highly susceptible to larger historical forces.

With the EU, of course, the two key forces are Islamic jihadism, whether imported from abroad or brewed at home, and emigration, worries about which was the key factor that led Britain to leave the EU.

With several more attacks in France like those in Paris and Nice, the influence of France’s National Front, with its hardline nationalist, anti-EU message, is only likely to grow.

Without Britain, the EU can stumble on. Without France, it cannot.