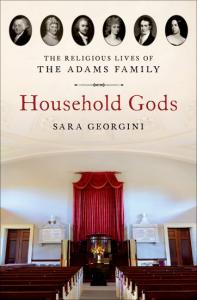

In 1815, John Quincy Adams purchased six small busts of classical philosophers and poets: Cicero, Homer, Plato, Virgil, Socrates, and Demosthenes. They stayed with him for the rest of his long life, sitting on the White House mantel and eventually resting in the Stone Library on the family’s Quincy property. Referred to by generations of Adamses as their Household Gods, they inspired the title for Sara Georgini’s portrait of one family’s centuries-long religious journey.

Georgini’s story begins with the decision of Henry Adams to bring himself and his family to New England in 1638 at the height of Archbishop Laud’s persecution of puritans. Household Gods ends with the decision of Brooks Adams (1848-1927) to sign the revised covenant of Quincy’s First Church. In between are an often dazzling procession of mini-biographies of Adams men (and their wives, to an unfortunately lesser extent) and their reckoning and refashioning of the “Christianities” they inherited from their fathers and forefathers.

At the outset, Georgini — a series editor for the Adams Family Papers at the Massachusetts Historical Society — observes that “the family remains a surprisingly understudied sphere for the development of faith.” True, despite the efforts of historians from Edmund Morgan to Charles Hambrick-Stowe to Laura Thacher Ulrich. It is easier to document the institution lives of churches and the careers of clergy than it is to peer into the conversations, devotions, and crises that shape how individuals live their religion within families. In the case of the Adamses, though, Georgini has an almost unparalleled family archive, as generations of Adamses wrote diaries and letters they expected would be preserved for posterity. It would have been easy for Georgini to write a massive tome based on this embarrassment of richly. Instead, she briskly tells a story of faith, doubt, and change.

At the outset, Georgini — a series editor for the Adams Family Papers at the Massachusetts Historical Society — observes that “the family remains a surprisingly understudied sphere for the development of faith.” True, despite the efforts of historians from Edmund Morgan to Charles Hambrick-Stowe to Laura Thacher Ulrich. It is easier to document the institution lives of churches and the careers of clergy than it is to peer into the conversations, devotions, and crises that shape how individuals live their religion within families. In the case of the Adamses, though, Georgini has an almost unparalleled family archive, as generations of Adamses wrote diaries and letters they expected would be preserved for posterity. It would have been easy for Georgini to write a massive tome based on this embarrassment of richly. Instead, she briskly tells a story of faith, doubt, and change.

The Adamses were all gifted writers. “I could scarcely believe myself an inhabitant of earth,” Abigail Adams observed after a performance of Handel’s Messiah at Westminster Abbey. Georgini also writes crisp and engaging prose. Publishers Weekly did her a disservice by criticizing her prose as “often overly dense and verbose.” It’s not. One of many counter-examples: “For Henry and Clover Adams, Christianity was no longer a viable practice. It was a punchline.” Or this: “Henry Adams’s Education may be the greatest con in American history writing.” For generations, the Adamses went to church and listened to sermons they frequently ignored. “Theological illiteracy was a point of pride, a pious badge,” Georgini concludes.

The generations of Adamses had many things in common: an aversion to creeds and dogma, a lust for travel, and a curiosity about other religions. Despite their combination of faith and doubt, though, Christianity remained pivotal “in shaping their decisions great and small about the course of the American republic that they served for three centuries.” Both Brooks Adams and his old brother Henry (1838-1918) lost their faith in both Christianity and the republic. The brothers’ father, Charles Francis Adams, had wrestled with his own skepticism but he nevertheless sought to instill a measure of Christian piety and devotion in his children. Both Brooks and Henry, however, loathed Sundays of psalm-reading and sermons. They rejected their inherited Christianity.

Henry Adams became a “full-on skeptic.” While he appreciated medieval Christianity’s power, he saw nothing to admire in the Christianity of his own day. “Young Henry quietly called off his search for God,” Georgini writes. He did not call off his search for peace and truth, however. He and his wife Marian (“Clover”) visited religious sites abroad, but unlike their parents and grandparents, they never joined a congregation upon their return home. Clover’s 1885 suicide devastated Henry. “I have not had the good luck to attend my own funeral,” he wrote, “but with that exception I have buried pretty nearly everything I lived for.” He set off for Kamakura, Japan, setting his gaze on a forty-foot Buddha. He went to Anuradhapura and saw the remains of the Bodi Tree where Gautama had attained nirvana. Henry Adams never found it himself, not in Japan, not in Quincy, not in the Virgin and not in the Dynamo.

Unlike his older brother, Brooks Adams partly renewed a faith once destroyed by a similar skepticism. Visits to cathedrals stirred Henry’s mind; the same places sometimes pierced Brooks’s soul. In 1907, Brooks joined Quincy’s church by making a public testimony of his own faith. He did not return to his great-grandfather’s faith in Providence, let alone to his ancestor Henry Adams’s puritanism (Brooks Adams loathed Calvinism and eviscerated seventeenth-century New England as a den of fanaticism and bigotry). But he rooted himself in a particular congregation, even as he remained a seeker. He visited a Portsmouth Benedictine friary. He felt an attraction to Catholicism.

Throughout her story, Georgini puts the Adams family within its evolving cultural context, from the American Enlightenment to “Victorian neurasthenia.” “Like most of their nineteenth-century peers,” Georgini writes, “they shook off the last restraints of Calvinism, explored foreign faiths, dabbled in biblical exegesis, and rejected theological hermeneutics in favor of aesthetic pursuits that infused Christian precepts and personalities into an emergent canon of national arts and letters.” That’s true if by peers Georgini means fabulously wealthy, blue-blooded Massachusettsans. The Adams men and their wives were very nearly peerless, born into careers of politics, law, and scholarship. And a fair amount of indolence, frankly. Certainly they were diligent diplomats and scholars, but not very many Americans had the chance to picnic on “champagne and partridge” near ancient Roman baths. Of course, Georgini does not lose sight of the unusual position of her subjects, and the almost singular nature of the Adams family doesn’t make her portrait less remarkable. Still, it is difficult to use the Henry and Brooks Adams to narrate broader currents of religious change, even in New England.

Also, I question her conclusion that as the years passed, family members’ “relationship with God became more intimate, as they pushed past clergy for a closer communion with holy precepts.” While the Adams men and women certainly charted their own courses, I am not confident that the nineteenth-century Adamses had more intimate relationships with God than the Henry and Edith Adams who stepped off the boat in 1638.

Household Gods made me think about the angst involved if one wants to maintain a Christian commitment while casting off the shackles of old creeds and practices; the difficulty many parents face when they seek to inculcate their children in a faith they value but do not fully understand or accept without questioning; and whether or not it is always possible to push on in the face of deep personal loss or national tragedy. There are many deeply moving human stories in this book, stories that resonate across the several generations that separate us from Henry and Brooks Adams.