Last time, I posted about the range of older “ghost” denominations and churches that preceded the specific church building you see before you. Think of them as the underlying substrata. If you know anything about denominations and their development, that opens the door to understanding a remarkable amount of the history of local areas, whether you are looking at issues of politics, class or, above all, ethnicity. That is true of rural areas and small towns, but also of large and medium size cities. With a little background, you can use churches to read a social landscape.

In giving an example, I have to be specific, as all American religious history is in a sense local. Let me talk about an area I know well, in Pennsylvania. In older communities, the pioneering churches (from the early or mid-nineteenth century) commonly belong to what today we would call three denominations, namely Presbyterian, Lutheran, and United Church of Christ, UCC, with Methodists not long afterwards. Often, the Lutheran and UCC buildings stand surprisingly close to each other, often on the same block, or just across the street.

So why those original three? The Presbyterians are easy to understand, as the founding white settlements here were Protestant Irish or Scotch-Irish, and that meant Presbyterian. But the other two are a separate story, which I tell to indicate just how complex is the background underlying the religious landscape we might take for granted.

That Lutheran/UCC mix reflects German-American origins, and it actually involves two traditions, namely the Lutheran and Reformed. The story begins with the Reformed (Calvinists) who were well represented among the German settlers of Pennsylvania in the eighteenth century. At the end of that century, we hear of ministers settling at Reformed churches in what were then the border territories in the center and west of the state. Germans continued to flood into the state in the early nineteenth century, but when they arrived, they came from a distinctive political/religious set up in their homelands. German states had both Lutheran and Reformed churches. During the Napoleonic wars, the Prussian state acquired other German regions with a diversity of denominations, and in 1817 the king decreed a Lutheran-Reformed union in his territories. Some resisted, but the union remained in place for decades.

Many of the German Protestants who arrived in Pennsylvania were either Lutheran or Reformed by tradition, but they duly established Union churches to serve both strands, sometimes with respective ministers officiating in different weeks. After a while, when settlements prospered, the two sides separated into their component parts, and they built two churches where one had been – one Lutheran, one Reformed. Usually, these were prosperous communities, and the new churches were very handsome indeed. That situation lasted for over a century, during which the Lutheran and Reformed churches were the real mainline in those Pennsylvania villages and cities. Brenda Gaydosh has a very readable account of the church’s history in the state.

Reformed believers of German or Swiss heritage were mainly concentrated in the Reformed Church in the United States, and the Evangelical Synod of North America. In 1926, the Lutheran Church was “the largest Protestant body in Pennsylvania with 551,000 members. The Reformed Church retained 216,000 members, ranking fifth behind Methodists, Presbyterians, and Baptists.” Beyond Pennsylvania, those German Reformed believers were widely found across Ohio and the Midwest, and into the upland South. The Evangelical Synod found its heart in Missouri and Illinois, where its twentieth century celebrities included Reinhold and Richard Niebuhr.

The German Reformed tradition was very active intellectually and spiritually:

The newly independent German Reformed Church, short of pastors and threatened by a revivalist gospel, established a seminary in 1825, at Carlisle, Pennsylvania, that moved in 1829 to York, in 1837 to Mercersburg and finally to Lancaster in 1871, where it became Lancaster Theological Seminary. Franklin College (1787) of Lancaster, jointly supported by the Lutherans and the Reformed, in 1853 merged with German Reformed Marshall College to form Franklin and Marshall College.

Scholar Philip Schaff was “the most outstanding church historian in 19th century America, and the primary mediator of German theology to America.” If you ever work on early church history or patristics, and you use the terrific Internet resources of the Christian Classics Ethereal Library, CCEL, you will come to appreciate Schaff’s scholarship very highly.

Like other Protestants, the German Reformed were split over issues of revivalism, and ministers like Philip Otterbein followed the revivalist example set by people like the Wesleys. In the nineteenth century, Reformed conservatives favored the more liturgical-oriented traditions stemming from the seminary at Mercersburg, and the work of Philip Schaff and John Nevin. This Mercersburg Theology was the German-American equivalent of the Oxford Movement in the Anglican and Episcopal churches, and like that movement, it inspired a lot of controversy, not to mention some real bile.

For obvious reasons, many “German Reformed” churches changed their signage in 1917 or thereabouts, to avert anti-German feeling during the First World War.

Matters changed in the mid-twentieth century with a series of new mergers and unions. In 1934, the Reformed Church and the Evangelical Synod merged to become the Evangelical and Reformed Church (E&R). In 1957, the E&R merged with the New England Congregational churches to found the UCC. Hence, all those small Pennsylvania towns acquired the now familiar mix of Lutheran and UCC, usually as close neighbors. In New England, UCC churches usually stem from Congregational roots.

Quite separate from the German story, Dutch Reformed believers meanwhile formed the unrelated Reformed Church in America. Others joined the Christian Reformed Church, best known perhaps for its association with Calvin University.

For the UCC, the new situation reflected more than new signage. The UCC quickly became one of the most liberal of denominations, and visiting a UCC church in Pennsylvania today can mean encountering a curious and even mysterious mashup of traditions and images. The building suggests a very “churchy” and traditional model of religion, but it may well be flying flags and banners celebrating LGBT or Trans causes, or social justice slogans. They are Open and Affirming. You might wonder how such very liberal and seemingly urban symbols ended up in small town or rural areas; but if you understand the history, you’ll immediately see why.

Not surprisingly, at least some rural churches have recently left the UCC on political grounds, but I have little sense how large that phenomenon is. For multiple reasons, not just ideological, the UCC is in deep trouble, and its membership rolls have collapsed dramatically even by the standards of the Protestant mainline denominations.

If you want a sad visual symbol of the loss of the once-mighty German Reformed churches that so flourished in the nineteenth century, in major cities as well as villages, see these grim images of the old First Reformed church in Cincinnati. What a fall was here.

As I say, the German Reformed and their various associates constitute one example, or rather one group of examples. But when you see a church sign citing a familiar denominational label like “Methodist” or “UCC,” it often pays to dig further and see how those names got there. That digging can often generate some interesting stories. I actually wonder if you went to one of those older Pennsylvania towns and asked if there had ever been a Reformed church around there, whether anyone would know. I suspect not. “That church over there? Oh no, that’s always been UCC.” But trust me, if you know the American religious scene, then the Reformed really mattered, and could have been a contender.

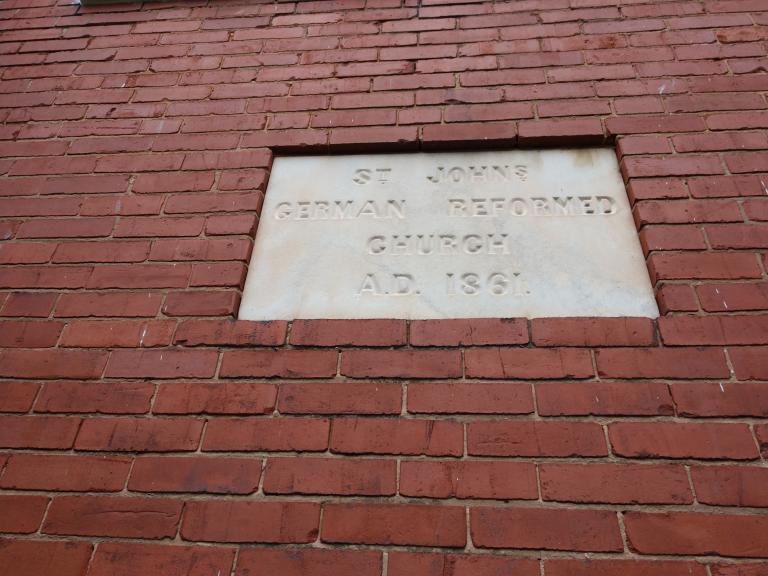

The moral again: if you want to understand a church, it pays to read the foundation stone. Denominational ghosts might be lurking there.

I can’t resist citing the title of the publication in which John Nevin attacked those obnoxious revivalists. It was The Anxious Bench – A Tract for the Times (Publication Office of the German Reformed Church, 1843), What a great name that would make for a blog.

In his second 1844 edition, Nevin noted the furious response that his original tract had received:

At least half a dozen of replies to it, shorter or longer, have been announced in different quarters, proceeding from no less than five different religious denominations. Various assaults, in addition to this, have been made upon it, from the pulpit ; to say nothing of the innumerable reproaches it has been required to suffer, in a more private way.

Thank heavens our own modern-day Anxious Bench does not venture into areas of sensitive debate.

All the photographs here are my own work.