By all measures, we live in polarized times. Against political norms, Republicans prepare to push through a Supreme Court nominee, and Democrats contemplate packing the court in retaliation. Toxicity and snark and uncharitable listening batter civil discourse from all sides. Perhaps we could take a lesson in political civility from some political antagonists in Jessamine County, Kentucky, in the late nineteenth century.

Some weeks before the 1888 election, fifteen local Democratic and Republican leaders made plans for a “game and oyster dinner.” To make it more interesting, they made a friendly wager. If Grover Cleveland, the Democratic candidate for president, won, the Republicans would foot the bill. If Benjamin Harrison, the Republican candidate, won, then the Democrats would pay.

As it turned out, Harrison won. But only barely—and without winning the popular vote. Though Cleveland outpaced Harrison 5,534,488 to 5,443,892 votes, Harrison easily beat Cleveland in the Electoral College 233 to 168.

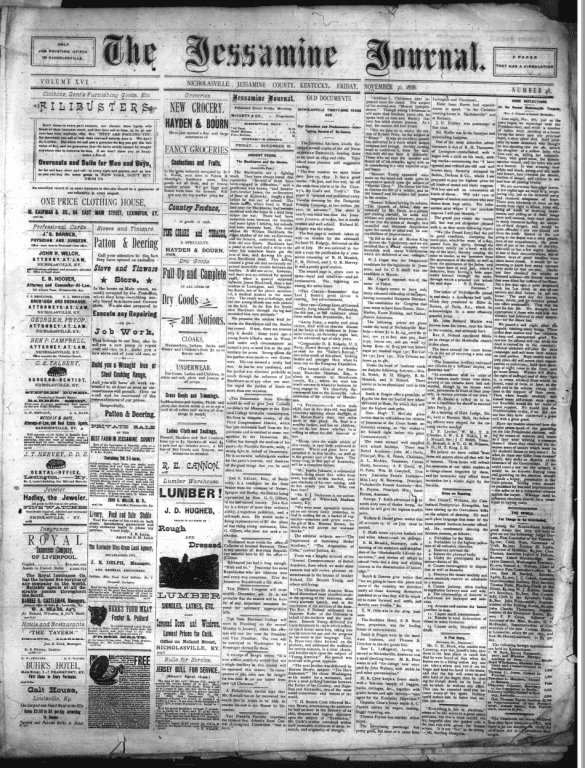

The tension, however, did not ruin the local dinner. On the Saturday evening after the election, businessmen, lawyers, editors, and farmers of both political persuasions showed up to Hotel Nicholas in downtown Nicholasville. H. C. Rodenbaugh arranged the sumptuous feast, serving up “everything good that you could think of.” It included venison, grouse, quail, oysters (raw, stewed, and fried), celery, ice creams, confections, and cakes. There was also wine for those who were not teetotalers. The Jessamine Journal reported that the champagne “is said to have been somewhat exhilarating.”

The food was accompanied by fine conversation. Some of the toasts and sentiments, said one report, “were not only original, but unique.” It was early Sunday morning by the time the dining room was empty, and the Journal pronounced it “a festive evening.” Can you imagine Matt Bevin, Kentucky’s previous governor, and Andy Beshear, Kentucky’s current governor, dining over oysters and celery? Not me.

But this was the pattern through the rest of the nineteenth century and for much of the twentieth century. And it intriguingly fits a suggestion by the social psychologist Jonathan Haidt in his book The Righteous Mind about why such rancorous polarization has set in with such intensity. Political opponents, Haidt observes, don’t hang out anymore.

Before the 1990s Democrats and Republicans socialized with each other. They went to church together. They drank together in D.C. pubs after work. Their wives played bridge together. Their kids went to the same elite private schools. “It’s difficult to call somebody a nasty name when your kid and their kid are in the Cub Scouts together,” says Emanuel Cleaver, a Democrat from Missouri, member of the Congressional Black Caucus, and a United Methodist minister.

But practices have changed in ways that limit civility. Closed primaries tend to result in fringe candidates. Gerrymandering allows parties to create partisan districts. Perhaps most damaging have been fundraising pressures that encourage politicians to live in their home districts rather than move to Washington. On one hand, this may keep them more responsive to their constituents. On the other hand, it keeps senators and representatives from forming bonds across party aisles.

But practices have changed in ways that limit civility. Closed primaries tend to result in fringe candidates. Gerrymandering allows parties to create partisan districts. Perhaps most damaging have been fundraising pressures that encourage politicians to live in their home districts rather than move to Washington. On one hand, this may keep them more responsive to their constituents. On the other hand, it keeps senators and representatives from forming bonds across party aisles.

Indeed, many of them simply do not know each other. “The only time I see a Republican,” said Cleaver last year, “is when I come up here (to the Capitol) to vote. Or go to a committee hearing.” It’s easy to construct an outgroup when the only things you know about that group come from FOX or MSNBC.

I don’t want to romanticize the good old days. In the 1980s privileged senators, nearly all of them white men, ruled the country from Capitol Hill and then slipped away to sleep and golf in Georgetown and Arlington. I also don’t want to romanticize Kentucky in the 1880s, when racial lynchings were commonplace. It was no accident that “the coloreds,” as the Jessamine Journal called African Americans back then, were not invited to this local dinner. In this era of Jim Crow, they weren’t even allowed inside Hotel Nicholas as guests. There were profound limits to the hospitality of this white supremacist men’s club.

Moreover, I don’t want to entirely denounce political tension. One of the reasons there is tension is because this is the most diverse Congress in American history. That’s a good thing.

But tension does not preclude civility. Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Antonin Scalia were ideological enemies. They were also opera buddies. Inspired by the memories of these Supreme Court justices, is it possible to imagine a nation—or better yet, a town or a state or a world—in which civility truly extends across racial, sexual, political, and religious lines? When Covid-19 is over, let’s once again gather together over quail and confections. Conservatives might douse the quail with ketchup, and liberals might substitute tofu. But that’s ok.