Among the many things to lament and resent about the attempted insurrection in the U.S. Capitol yesterday afternoon was the way it shifted attention away from the history made the previous night in Georgia. A state that is over 30% African American elected its first Black senator: Raphael Warnock. Not only unprecedented in that important respect, Warnock’s election is also stands out because of his occupation. In legislative bodies dominated by lawyers and business people, only 2% of the U.S. House and Senate are ordained clergy like Warnock, the senior pastor of Ebenezer Baptist Church, the Atlanta congregation that Martin Luther King, Jr. co-pastored with his father in the 1960s.

When he takes his seat in the Senate, Warnock will join James Lankford (R-Oklahoma), whose official bio opens with his “more than 20 years in ministry, including 15 years as the Director of Student Ministry for the Baptist Convention of Oklahoma and Director of the Falls Creek Youth Camp, the largest youth camp in the United States, with more than 51,000 individuals attending each summer.” Of course, we might also count Mitt Romney, who has long been a highly active lay leader in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, which ordains men as priests at age 16. (I’m less sure how active other Mormon senators — like Romney’s fellow Utahn, Mike Lee, or outgoing New Mexico Democrat Tom Udall — have been in their stakes.)

Entering November’s elections, only seven of the 435 members of the House of Representatives listed “ordained minister” in their occupational profile. That list included two more Baptists from Georgia: Republicans Jody Hice and Doug Collins, who gave up his spot in the House to challenge for the Senate seat ultimately won by Warnock. Another Baptist minister endorsed by the GOP, Johnny Teague, lost to incumbent Al Green in Texas’ 9th district. And in Kristin’s neck of the woods in western Michigan, Calvin Seminary grad and UCC pastor Bryan Berghoef was unable to unseat Republican Bill Huizenga (a Calvin College alum).

I don’t know the full updated count, but one way or another, the 117th Congress will have proportionally fewer pastor-legislators than the 1st. Almost 10% of the initial House membership were clergymen, including the first speaker, Frederick Muhlenberg, son of the founder of American Lutheranism, Heinrich Melchior Mühlenberg. (Both were educated by Pietists at the University of Halle, I feel bound to add.)

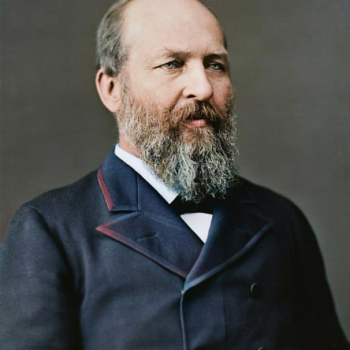

All were Protestants — as was America’s only pastor-president, one-time Disciples of Christ preacher James Garfield. But the House has also seated two Catholic priests, both in the 1970s. Robert Drinan, a Jesuit from Massachusetts, opposed the Vietnam War and (as Warnock does) supported abortion rights. Fellow Democrat Robert John Cornell, a priest — and history professor! — from Wisconsin, was voted out in 1978 and dropped his 1980 comeback attempt after Pope John Paul II forbade Catholic clergy from holding political office.

But historically, the most significant type of pastor in congressional history — with all due respect to legislators like the long-serving former Missouri senator John Danforth, an Episcopal priest — has been Black ministers like Warnock. In the current Congress, the Georgia senator will join two Democratic representatives from Missouri: Emanuel Cleaver, a Methodist pastor who made the news last week for ending an invocation prayer “Amen and a-woman” (a phrase not uncommon in Black churches); and Cori Bush, who responded to yesterday’s shocking events by calling for the expulsion of Republican legislators she blamed for helping to incite the violence. (Meanwhile, Sen. Lankford, whose speech was cut off when the Senate went into lockdown, came back last night and made clear that he would abandon his earlier intention to challenge the results.) Earlier in his career, Warnock served as youth pastor at Abyssinian Baptist Church, the historic New York congregation where Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. had succeeded his father as pastor before embarking on a long stint in the House of Representatives.

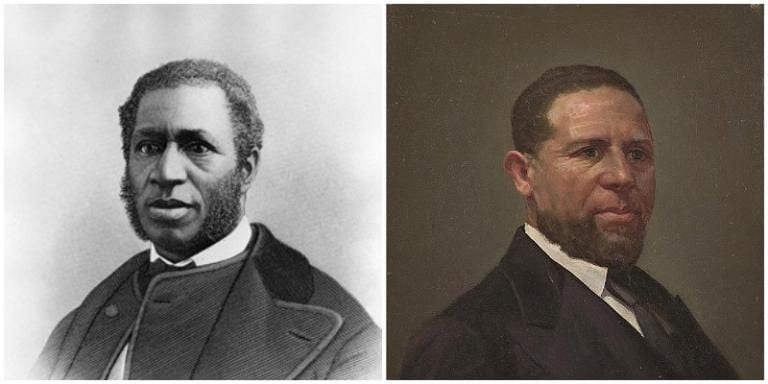

That tradition of Black church leaders entering Congress began during Reconstruction, the attempt at multi-racial democracy that ended with the cynical compromise that followed the contested election of 1876 (in the news for other reasons thanks to some Republican senators). The Senate’s first Black member was Hiram Revels, an ordained Methodist minister who had preached in the Midwest before becoming a chaplain in the Union Army and then entering Republican politics in Mississippi. For part of the 1870s, South Carolina was represented in the House by Richard Harvey Cain, pastor of Charleston’s historic Mother Emanuel Church.

For all the overlap between occupations that require abilities in public speaking and leadership, there are good reasons for a society that separates church and state to be cautious about entrusting too much political power to too many pastors. Indeed, as political scientist Robert Scheel points out, several states prohibited members of the clergy from serving in their legislatures, until a 1978 Supreme Court decision struck down such statutes on First Amendment grounds.

But Warnock sees a continuity running through his callings. “It’s unusual for a pastor to get involved in something as messy as politics,” he acknowledged in November, “but I see this as a continuation of a life of service: first as an agitator, then an advocate, and hopefully next as a legislator.” And as Deseret News reporter Mya Jaradat noted, in a late October article dedicated in part to Warnock’s candidacy, “it has always made sense for Black pastors to step into the public square. In the past, segregation and other legal and social barriers that prevented Black Americans from participating fully in society pushed politics into the church, which served as a safe haven for both discussion and organization.”

As Rev. Warnock prepares to represent the people of Georgia in the U.S. Senate, it’s worth remembering that Hiram Revels’ first speech before that same body had to do with that state’s application for readmission to the Union in 1870. Drawing on skills he had honed in the Black church, Revels made a religious appeal for political equality, unsuccessfully opposing an amendment that would foreclose public office to people like him and Raphael Warnock for decades to come:

They longed… as their fathers did before them, for the advent of that epoch over which was shed the hallowed light of inspiration itself. Weary years of bondage had told their tale of sorrow to the court of Heaven. In the councils of the great Father of all they knew the adjudication of their case, albeit delayed for years, in which patient suffering had nearly exhausted itself, would in the end bring to them the boon for which they sighed—God’s most blessed gift to His creatures—the inestimable boon of liberty…. They aim not to elevate themselves by sacrificing one single interest of their white fellow-citizens. They ask but the rights which are theirs by God’s universal law, and which are the natural outgrowth, the logical sequence of the condition in which the legislative enactments of this nation have placed them.