Forty-nine years ago today, the Supreme Court of the United States announced its decision in the case of William Henry Furman, sentenced to death in Georgia after he accidentally shot the owner of the home he was burglarizing. “The criminal acts with which we are confronted are ugly, vicious, reprehensible acts,” acknowledged Justice Thurgood Marshall, yet he and four other members of the nation’s highest court not only upheld Furman’s appeal but imposed a moratorium on all executions.

The narrow majority shared the great civil rights attorney’s concern that “capital punishment is imposed discriminatorily against certain identifiable classes of people,” that “the burden of capital punishment falls upon the poor, the ignorant, and the underprivileged” — particularly Black men like Furman. But most did not join Marshall in concluding that capital punishment itself violated the 8th Amendment’s ban on “cruel and unusual punishment.” So while he celebrated Furman v. Georgia as evidence of continued progress in a country that “clings to fundamental principles, cherishes its constitutional heritage, and rejects simple solutions that compromise the values that lie at the roots of our democratic system,” the moratorium on the death penalty lasted just four years.

In 1976, SCOTUS ruled 7-2 in favor of Georgia, which, after updating its guidelines in line with the Furman decision, had sentenced Troy Leon Gregg to death for killing two men he was trying to rob. Since that decision, over 1,500 Americans have been executed by their government.

The Gregg decision came despite the efforts of ACLU lawyer Henry Schwarzschild, a Jewish emigré from Nazi Germany who tried to enlist Christian allies as part of the coalition against the death penalty. As historian Aaron Griffith reports in God’s Law and Order, Schwarzschild hoped that the National Association of Evangelicals would join mainline Protestant denominations in formally opposing capital punishment. But NAE public affairs secretary Floyd Robertson not only quoted back to him the NAE’s post-Furman resolution in strong support of the death penalty — “From the biblical perspective, if capital punishment is eliminated, the value of human life is reduced and the respect for life is correspondingly eroded” — but argued that such a penalty helped encourage sinners to make last-minute conversions to Christ.

The horrified Schwarzschild could not believe that followers of Jesus would ever desire to “terrorize and kill others into a love of God,” but Griffith puts the NAE’s response in the context of longstanding evangelical support for capital punishment — and part of a larger affinity for the government upholding “law and order.” You won’t do better than to read Griffith’s acclaimed book on the subject, which you can preview via this December 2020 interview here at Anxious Bench.

But given today’s anniversary of the Furman decision, I thought it’d also be worth pointing out that there has always been evangelical opposition to the death penalty, too, some of it even receiving a platform from flagship evangelical institutions.

A few months after publishing Presbyterian theologian Jacob Vellenga’s essay in staunch support of capital punishment, in 1960 Christianity Today shared counterpoints from John Howard Yoder and Charles Milligan. Three years later CT interviewed the Republican governor of Oregon, Mark Hatfield, who professed himself “opposed to capital punishment” — not “on a religious basis, because frankly I have not yet been convinced that our faith is clear cut in its teaching one way or the other. I’m opposed to capital punishment because of economics—the inequity of its application—that is, the poor die and the rich get off.” During his long stint in the U.S. Senate, Hatfield — like other subjects of David’s book on progressive evangelicals — continued to oppose capital punishment, as part of a consistent pro-life ethic that also included opposition to abortion and support for a nuclear freeze.

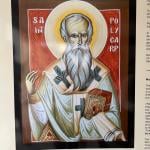

Meanwhile, Christianity Today periodically checked in with both sides of the debate in the decades after Gregg v. Georgia. In 2014, a year after retiring as the magazine’s editor-in-chief, David Neff used his column to survey patristic antipathy to the death penalty and call for an evangelical reevaluation of the practice: “It is time for us to take another look at what Jesus and those earliest Christian writers had to say about the value of human life, no matter how sinful that life may have been.”

The following year, the National Association of Evangelicals updated its resolution on capital punishment, affirming “the conscientious commitment” of opponents and supporters alike. Without actually rejecting the death penalty as a legitimate means for governments to fulfill their divine calling “to administer justice to protect citizens and preserve the common good,” the NAE honored biblical and theological arguments “either against the death penalty or against its continued use in a society where biblical standards of justice are difficult to reach.” By 2015, even evangelicals who did not flatly reject capital punishment were becoming increasingly uneasy with a penalty that, in too many cases, was being applied unjustly.

It wasn’t just that technological progress had introduced DNA evidence into the legal process, helping to prove the innocence of some eighteen death row inmates so far. There seemed to be a reawakening to Marshall’s original concern about the social inequalities and injustices woven into the system of capital punishment, a shift that Robert Jones attributed in part to the growing influence of Black and Hispanic evangelicals. For example, when the increasingly multi-ethnic Evangelical Covenant Church adopted a new resolution on criminal justice in 2010, it did not stake out a specific position on the death penalty, but did draw particular attention to the problem of racial disparities in incarceration and sentencing — including capital cases. Four years later, Christian college graduate Bryan Stephenson published Just Mercy, a memoir of his work with the Equal Justice Initiative, starting with the case of a wrongly convicted Black man awaiting execution.

Stephenson’s book caught the attention of pastors like Wes Helm, one of fifty evangelicals who tried to convince Texas governor Greg Abbott to stop the execution of Jeff Wood in August 2016. (That state alone accounts for more than a third of the post-Gregg executions.) Another signatory to that letter was the Hispanic evangelical leader Samuel Rodriguez, who had started to publicly rethink capital punishment two years earlier, after a botched execution in Oklahoma. The Wood case led a journalism project named for Thurgood Marshall to ask if evangelicals were “ditching the death penalty.”

Of course, it was mere months later that the vast majority of white evangelicals who voted for president cast ballots for Donald Trump. Having sounded familiar “law and order” themes as a candidate, President Trump reinstated the death penalty for federal cases — with thirteen executions carried out under his administration, ten in 2020 alone. Writing at his CT blog the month after Joe Biden’s victory, Scot McKnight called Trump’s execution record “a morbid new distinction” and called on Christians to “include opposition to the death penalty as an element of being completely pro-life.”

Yet white evangelicals remain the religious group most strongly supportive of capital punishment: 75% of them supporting the death penalty for murder in a survey released this month by Pew, twenty points higher than the much-narrower majorities in support found among white Catholics and the religiously unaffiliated. And while 50% of Black Protestants — including evangelicals — oppose the death penalty altogether, it seems highly unlikely that the Supreme Court’s conservative supermajority will revive anything like the Furman moratorium, despite the evidence that capital punishment continues (in Marshall’s words from 1972) to be “imposed discriminatorily against certain identifiable classes of people.”

Evangelicals like Rodriguez, McKnight, and Shane Claiborne continue to join activists like Stephenson in decrying the injustice or even immorality of capital punishment. But I suspect that most of their fellow believers are quite satisfied that the Trump presidency has rewarded their votes with a Supreme Court that is both pro-life and pro-death penalty.