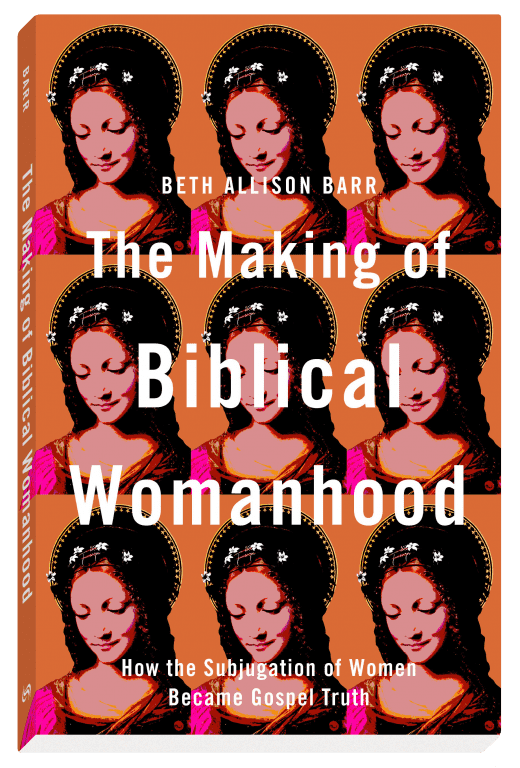

This week marks the one year anniversary of The Making of Biblical Womanhood: How the Subjugation of Women Became Gospel Truth. Since the book was born in my blogging on The Anxious Bench, I thought it fitting that my postcript publish here as well. You can also find it on the Baker Book page for #MakingBiblicalWomanhood. It is a joy and privilege to continue to write in this space. Thank you for your faithful readership.

This week marks the one year anniversary of The Making of Biblical Womanhood: How the Subjugation of Women Became Gospel Truth. Since the book was born in my blogging on The Anxious Bench, I thought it fitting that my postcript publish here as well. You can also find it on the Baker Book page for #MakingBiblicalWomanhood. It is a joy and privilege to continue to write in this space. Thank you for your faithful readership.

A Postscript

Mostly I remember the sounds. The tone of his voice. The tires squealing around an abrupt curve. The soda can rattling in the cup holder. Just normal sounds, twisted by trauma into a cacophony, overwhelming the small space of the car.

I also remember the silence. It wrapped around me in the cold night air, calming my body and helping me breathe after I finally got away from him. Silence didn’t erase the harsh sounds of the car; it didn’t erase what happened. It just cleared my head and helped me get home.

More than a year had passed since I attended a series of seminars led by the conservative speaker Bill Gothard. More than a year since I had found myself in an increasingly unhealthy dating relationship predicated on authoritarian ideals of male headship and female submission. I had known for a long time that something was wrong. This night—the speeding car, the verbal threats (as I perceived them), the anger—solidified for me how horribly wrong it was.

When the fear finally came, when my hands shook so violently I couldn’t open the door, I sank to the floor. It was a strange fear, though. A numb, almost out-of-body disbelief that surely this wasn’t happening to me; surely it wasn’t real. Except I knew it was, and I could no longer pretend I was okay. My fear that night was more about the future than the present; more about what could happen to me than what had happened to me. I understood, maybe for the first time, that I had to get out.

By the grace of God, I did.

The waking nightmares followed a few months later—triggered mostly by sound. Just a car accelerating too quickly would flood my senses. Once, after finding myself parked on the shoulder of the road and struggling to breathe, I realized I needed help. Counseling combined with strong support networks soothed the raw edges of my pain. I found I could sleep again. I found I could forgive. I found I could move on.

But I didn’t forget. Did you know that trauma has memory? So much time had passed since that night. Since that whole chapter of my life, when I lived as an unreported statistic of relationship abuse, I couldn’t remember the last time it had affected me. That is, until the Gospel Coalition published a review of The Making of Biblical Womanhood: How the Subjugation of Women Became Gospel Truth. The review was written by Kevin DeYoung, pastor at Christ Covenant Church in Matthews, North Carolina; associate professor of systematic theology at Reformed Theological Seminary; and a member of the Gospel Coalition council. I had tried to read it on July 19, the day it was published, but I only

managed a skim. It wasn’t until three days later that I read through all five thousand words. July 22 became the day I realized how much trauma my body remembered.

*****

“Mom. Mom!”

My son was standing behind me. I was sitting at our kitchen counter, iPad open to the review. But I no longer saw it. My eyes had gone fuzzy. Apparently my ears had too, as I had not heard my son barreling in from tennis practice. I hadn’t heard the clatter of his rackets hitting the table or the barked greeting of our dogs. It wasn’t until he called my name that the fog lifted. His question wasn’t difficult. Just the usual, “What’s for dinner?” Less usual was his follow-up: “Mom, are you okay?”

For the first time in years I had heard that long silent voice. I had heard it screaming alongside the screech of tires, and my body had frozen—just as it had done so long ago. It shocked me. I never expected the voice of the review to trigger the voice from my long-ago past. My son’s voice pulled me back, pushing me to stand up and dig through the fridge for dinner possibilities. But it wasn’t until later that evening, as we sat together on the couch, that I began to understand what had happened.

It wasn’t the circumstances. Written words (no matter how callous) are not the same as an unhealthy relationship. It was the tone, I think, that brought my traumatic memories to the surface. The demeanor of the review—DeYoung’s skepticism of my story, his assumption that men would tell a different (better) account of my experiences, his suggestion that my experience in an abusive relationship undermined my scholarly credibility, his scoffing at my credentials, his confidence that he understood medieval women’s history better than a scholar of medieval women’s history did—threw me back into the very world I thought I had escaped: the world where Christian women live, by God’s decree, as less than men.

Something else happened that night. My husband and daughter were out of town, leaving me alone with my son for the week. I promised to binge-watch Loki with him. But first I had one more Zoom event. It was a book club. Yes, of course I would love to join them. I would love to answer their questions and be a part of the discussion. But that was this morning, before I had fully read DeYoung’s review. Now my hands trembled as I set up my computer, plugging in my headphones and turning on the camera. Now things were different, and my heart just wasn’t in it.

To my surprise, the book club—unaware of DeYoung’s review—had planned something different. When I logged on, they didn’t ask me to talk. Instead, they asked me to listen. One by one, each woman told me how The Making of Biblical Womanhood had changed her life. Each thanked me for writing, for not staying silent. Hundreds of miles separated me from that roomful of women, but for one hour we came together as they shared how this book had set them free.

What they didn’t realize was that their words set me free too.

“Are you ready, mom?” My son stood in the doorway, waiting to watch. “Yes,” I said, closing my laptop. “I am ready.”

I still felt winded by the gut punch of the review. But God had used that book club to strengthen me. It was true that a small group of mostly white, conservative men were cheering DeYoung’s words, tweeting and retweeting his review, shouldering him as the hero who would save Christian patriarchy. Yet it was also true that an everincreasing number of women and men were quietly reading and sharing The Making of Biblical Womanhood. The former group was making the loudest noise, digging in their heels and drawing lines in the sand. But it is the latter group—the women and men who, one by one, are standing to fight for women within the small circles of their family, friends, and churches—who, I think, will matter the most.

THE QUIET REFORMATION IN NORWICH

It was 2003. I didn’t know how to silence my cell phone. It was the first one I had owned, and I worried it would ring during the conference panel. A colleague in my graduate program solved the problem by removing the battery. I could see her dropping the now-disabled phone in her bag before giving me a thumbs-up. Relieved, I took my seat at the front of the room alongside the other panelists.

In a little over two months I would defend my dissertation, “Gendered Lessons: The Pastoral Care of Women in Late Medieval England,” at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. This was my last conference appearance as a graduate student. David Postles was chairing the North American Conference on British Studies panel along with Barbara Harris, who served as commentator. The session consisted of papers by Katherine French, Muriel McClendon, and me—then an all-but-dissertation PhD candidate.

French’s scholarship was already important to me. Two of her articles had reframed how my evangelical mind thought about women in the medieval parish. The small Annie Armstrong tin that sat on my childhood dresser, collecting loose change to support North American missions, was a far less exciting fundraiser than fifteenthcentury Hocktide festivals (in which women chased, tied up, and ransomed men for money). Women led in both church fundraisers—the Baptist Women’s Missionary Union launched the home missions offering in 1895, renaming it the Annie Armstrong Easter offering in 1934, and medieval women participating in Hocktide festivals raised consistently more money than men for their parishes. Churchwarden accounts from Croscombe (Somerset) showed that “a maiden’s guild” raised 30 percent of the total parochial income in 1493, and the wives in Ashburton (Somerset) in 1491 were “more enthusiastic about their work” in the church than men were and contributed “more money than the men.” My Southern Baptist mind grappled with the reality of women who lived before the Reformation yet worked as vigorously for their medieval Catholic faith as did the 1904 Baptist Ladies Aid Society, which raised $10.80 at an ice cream social to repair the window blinds at a small Texas church. I’d been staring at women through fifteenth-century sermons for so long that I had forgotten to look at the real women who listened to those sermons. French’s scholarship taught me that if I wanted to understand the vibrancy of medieval women’s faith, I needed to consider the lived experiences of women alongside prescriptive literature about them.

Muriel McClendon’s scholarship, however, was new to me. I knew of her book The Quiet Reformation: Magistrates and the Emergence of Protestantism in Tudor Norwich, but I didn’t read it until after the panel. Listen to her argument:

“Norwich was an important religious center, the seat of one of the largest dioceses in late medieval and early modern England and a hub of Puritan activity in the Elizabethan era. When beginning this project, I expected to find widespread conflict over religion, because such conflict has been a major theme of the recent historiography of the English Reformation. . . . Yet . . . open conflicts over religion were fewer in number and lesser in intensity than I had anticipated. . . . While a genuine Reformation certainly occurred in Norwich, its course appears unusually quiet compared to what we know about other English towns.”

McClendon expected sixteenth-century Norwich to be a hotbed of religious conflict. As she explained, the city had a long history of conflict—religious, jurisdictional, and economic. The city also had a strong commitment to medieval Catholicism: forty-six active parish churches in the 1520s, a plethora of monastic houses as well as hermits and anchorites (like the fourteenth-century anchoress Julian of Norwich), communities of nun-like women, and even evidence of citizens faithfully supporting local churches. “Ninety-five percent of lay men and women,” wrote McClendon, “bequeathed money to at least one parish church.” Her hypothesis, then, was sound. Given the evidence from Norwich (not to mention the reality of religious conflict in comparable towns), it seemed likely that the birth pangs of Protestantism in Norwich would be painful.

Except they weren’t.

Norwich quietly converted to Protestantism while the town of Bristol split down the middle (becoming the site of such “protracted and noisy disturbances” that the city officials launched an investigation into

seditious acts) and neighboring towns in East Anglia—such as Ipswich and Stoke—as well as London, Chichester, and Coventry witnessed outbursts of iconoclasm. By the midpoint of Elizabeth I’s reign, Norwich had earned the “reputation as an important hub of Puritan activity.” It wasn’t an easy transition—change is usually hard. But it was a less violent, less noisy, and more complete conversion than that experienced by neighboring cities.

The question is, Why? Why did a quiet reformation take place in Norwich as opposed to the open conflicts elsewhere.

McClendon’s answer is simple, and surprising: the city officials. The local magistrates prioritized the smooth governance of their city over theological disagreements. They knew the cost of religious turmoil (it was everywhere around them) and chose a different path. Instead of exacerbating religious divisions, which would lead to violence and unwelcome state interference, the local magistrates promoted religious toleration (i.e., they didn’t call each other wolves and vultures). Instead of hunting down dissidents and characterizing those who were rejecting Protestantism (or a particular brand of Protestantism) as morally suspect, the local magistrates chose to “compartmentalize their religious beliefs, effectively creating a distinction between private religious belief on the one hand, and public action and civic loyalty on the other.” Instead of forcing the townspeople to choose sides (between Catholic and Protestant,

or between different factions of Protestantism), a group of sixteenth-century civic leaders found a way to coexist.

Isn’t that interesting?

Reformation still came to Norwich. The drama, as my daughter would say, was just less. The cost to the city was less too. Yet the transformation was just as significant.

On July 22, 2021, more than eighteen years after the panel presentation with French and McClendon, I thought about McClendon’s argument and the quiet reformation in Norwich. I thought about it as I processed the significance of that online book club. To be sure, it wasn’t an exact correlation. Change in Norwich was top-down, stemming from elite city officials, whereas the type of change represented by the book club was more bottom-up, stemming from ordinary men and women no longer satisfied with the status quo. Yet even with these differences, I couldn’t stop thinking about Norwich. I couldn’t stop thinking about how Protestantism took root and spread quickly in that sixteenth-century city—not because of haranguing preachers or the violent destruction of shrines within parish churches but because of the ordinary decisions made by civic officials trying to protect their city. Instead of following the example of cities around them, the magistrates in Norwich chose not to support the status quo of religious strife. Their ordinary decisions rippled outward and made lasting change.

This is what struck me: the impact of ordinary decisions that launched a quiet reformation in Norwich. Was it possible that ordinary decisions like those made by the book club participants could create the same kind of lasting change? One woman had read The Making of Biblical Womanhood and then shared it with a friend. A simple decision. A quiet decision. Yet a decision that multiplied into a roomful of women who now knew the historical truth about biblical womanhood.

It seems ironic to me that the day I read DeYoung’s review was also the day I began to hope that message of The Making of Biblical Womanhood might be having a positive effect. Of course, I had already realized that if the book was dangerous enough to warrant a five-thousand-word refutation, the audience I wanted to reach was probably being reached. What really gave me hope that day was the book club. I realized that underneath the social media noise and the loud cries of wolf, people were reading The Making of Biblical Womanhood; they were passing it along to their friends and family; they were adding it to their shelves on Goodreads.com; and some were starting to change their minds.

The public conflict over The Making of Biblical Womanhood was loud and ugly, but the quiet reformation playing out behind the scenes was just getting started.

SETTING WOMEN FREE

Would you believe that I almost didn’t sign the contract for The Making of Biblical Womanhood?

I let it sit at the end of our counter for almost a week. Occasionally, I would pick it up and look at it. Once, after watching me do this, my husband asked a fair question.

“Are you going to sign that?” His words were familiar to me, recycled from my own thoughts.

“I think so,” I would answer. But I didn’t know.

I didn’t know if I wanted to write it; I didn’t know if the cost would be worth it. Would it be worth it if I was accused of not believing the Bible? Would it be worth it if my identity as a scholar was questioned because of my identity as a Christian? Would it be worth it for so many people to know the hardest stories of my life? I also worried about the cost for my family. Would it be too high?

One year after publication, I can tell you that my fears were valid. Social media continues to buzz with attempts to undermine The Making of Biblical Womanhood as well as my credibility as a scholar and a committed Christian. From skepticism cast on both my scholarship and my story, mostly by white conservative evangelical men whose identities are wrapped up in maintaining rigid gender hierarchies, to attacks on my credentials, my identity as a mother, and even the orthodoxy of my local church, almost every fear I had about writing the book has come to pass.

One year after publication, I can also tell you that my hope was valid too. Behind the scenes, my social media direct messages and my email buzz with letters that offset the public resistance. It has been 366 days since The Making of Biblical Womanhood officially released. Almost every one of those days I have received at least one letter—sometimes multiple letters—from people thanking me for writing the book.

Some of the letters come with gifts—books and handmade items like knitted washcloths in the colors of the book cover (which I love and use almost every day). One letter contained a green plastic soldier. A sign was taped over the cannon on his shoulder with the printed words “Front toward Patriarchy.” One letter was mailed in an envelope made from old Wonder Woman comic strips. I can’t help thinking that the scene on the front was deliberately chosen, because it shows Wonder Woman breaking her chains.

Mostly, the letters are just words, sent from all over the world. And they tell me a different narrative than what I hear from the loudest voices on social media. Take, for example, this letter I received a few months ago from a young woman in China. Her pastor sent the letter for her. He told me she had read The Making of Biblical Womanhood, and he wanted me to know the impact it had on her. Listen to some of her words:

“When I was reading your book, I was crying almost in every chapter. It’s such a shocking realization how deep the patriarchal system is poisoning the Christian worldview. It has let Christianity become a weapon toward women. I suddenly found that I had lost the joy of “finding Jesus” in my life for so long. . . . I took in the “headship of men” doctrine and persuaded myself again and again that it was me who was the problem. . . . Thankfully, I got the chance to read your book, and I’m finding my Jesus back, who is actually for me and not against me, who is for women and not against women. . . . Thank you for speaking up and choosing not to stay silent anymore!”

The timing of some of these notes seems providential. Another one came three weeks after the Council for Biblical Manhood and Womanhood (CBMW), described on their website as the flagship organization for complementarianism, mentioned our church in a letter soliciting funds for their cause. Apparently the website of our tiny Baptist congregation (whose members mostly never read the website) contained a word so dangerous to orthodoxy that the CBMW called for it to be “rejected by confessional Christians.” The word Godself (which appeared on the church’s website before we even joined the church) wasn’t dangerous in and of itself; it became dangerous because I had written The Making of Biblical Womanhood, which threatens the founding premise of the CBMW. My husband and I spent a shocked few hours deciding if or how to respond. “Lord, you brought us to this place for love of you,” I remember praying, using words inspired by Margery Kempe in the fifteenth century. “Be with us and have mercy on us.”

God answered in a mighty way.

The fundraising letter for the CBMW worked—just not in the way they intended. People all over the world began to give money to our church instead. Within a few hours, more than $11,000 had been raised. The final tally would be $40,000, given by more than 320 individuals and organizations. It was an exhilarating experience; it was an exhausting experience; and it was a terrifying experience. I had not expected such a public and personal attack. Despite the swell of support on Twitter of those reaching out to support my church, I began to wonder once again about the cost of writing The Making of Biblical Womanhood.

Until I opened my email.

I read the words of a woman who found her Jesus again. I read her letter several times through. Then I read it to my husband. When he sent me the draft of his thank-you note to those who had given so much to our church, his words seemed to echo this woman’s testimony. This is what my husband wrote: “When my wife, Beth, decided to write The Making of Biblical Womanhood, we knew that it would provoke a response from those whose identity is embedded in complementarian theology, but our hope was that it would also be a catalyst for freedom and change that would unleash more women to fully embrace their God-given callings and giftings. It is our joy to report that this is the case.”

It is our joy, indeed, to report that The Making of Biblical Womanhood has become a catalyst for freedom and change that is unleashing women to fully embrace their God-given callings and giftings.

The Making of Biblical Womanhood is helping to set women free.

A woman who wrote to me just a few weeks ago made this even clearer. A controversial point I argue in the book is that ideas about women matter. Ideas that posit that women are second-class citizens in the kingdom of God lead not only to men treating women as less-than but also to women believing they are less. Many have reproached me for writing this. People behaving badly doesn’t equal bad theology, they have argued. They say that wives graciously submitting to the loving servant leadership of their husbands is a beautiful vision; that a male pastor standing in the place of a male savior, beckoning us to follow him as he follows Christ is a beautiful vision. Complementarianism isn’t a broken theology, they tell me; it is a beautiful theology embodied by broken people. Just because God calls women and men to different roles doesn’t make women unequal to men.

Except that it does.

Just think about it. Is equality (much less equity) possible when women (simply because of their bodies) are limited in ways that men (simply because of their bodies) are not? If men (simply because of their sex) have the potential to preach, exercise spiritual authority over a church congregation, and exercise authority over the home, but women (simply because of their sex) do not, doesn’t that suggest that something is lacking in how God created women? Could the beautiful vision of complementarity be not so beautiful at all because at its root lies the assumption that the personhood of a woman is less than the personhood of a man?

I still remember the moment I finally grasped the impact of complementarian teachings about women. I was sitting in our high school youth room. My husband was going through a “how to teach” series and had asked one of the young women to lead that night. However, he had to justify why she was able to do that. As I listened to him, I realized that all those young men in the room were being taught that there was something innate in their masculinity that made them able to lead in a way that this young woman never could. Not because of their character. Not because of their skill set. Not because of how God had called them. Simply because their male body placed them in authority over female bodies.

Women internalize this teaching, as the woman who wrote me just a few weeks ago made clear. Listen to her words:

“I have only ever been in complementarian churches. . . . I have struggled for a long time to reconcile what I felt with what I had been taught, and it was a losing battle. . . . This contributed to me wrestling with my value and worth as a person. I started your book yesterday (I’ve nearly finished it today), and yesterday as I read, a thought hit me like a freight train. “Maybe God actually doesn’t view me as lesser than men.” I wept. Because it was the first time I had good evidence and reason to back up how I’d felt for so long. The idea that maybe Jesus desired for the radical freeing of women instead of their suppression was a breath of fresh air I so desperately needed. You don’t need to reply to this email. I just needed to tell you thank you for speaking up. Thank you for writing this book.”

Complementarianism taught this woman, in her own words, that God viewed her as less than men. She internalized inequality with inferiority. When she realized that maybe the problem wasn’t with God but rather with what she had been taught about God, when she realized that “maybe Jesus desired the radical freeing of women instead of their suppression,” she wept tears of relief.

This is why I wrote The Making of Biblical Womanhood.

To help the woman who found her Jesus again.

To help the woman who found her value and worth again.

To help the women in that book club—in every book club—be empowered to preach, teach, and lead as God has called them.

I haven’t told you the whole story of that July 22 book club. They didn’t just read The Making of Biblical Womanhood; they acted on it. “They want to write a letter to our elder board [about] why we should have female elders,” the organizer told me. “Our church is changing because of your scholarship! Thank you seems a little small.” I smiled when I read her words. My book may have inspired her book club to act, but it is their decision to act that will inspire lasting change.

Muriel McClendon found that the decisions made by civic leaders in sixteenth-century Norwich—decisions to stand against the status quo of religious strife—quietly transformed a city. The behind-the-scenes responses to The Making of Biblical Womanhood—the book clubs, the letters, the people who drop by my office and stop me in the grocery store line—give me hope that similar transformation is possible for the evangelical church.

Maybe this time a quiet reformation will finally set women free.

Go, be free, y’all! And if you want to know what is next: see my new book announcement here.

References

- At that time, David Postles was a senior research fellow at the University of Hertfordshire; Barbara Harris was a professor of history at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; Katherine French was an assistant professor of history at the State University of New York–New Paltz, recent holder of a visiting lectureship in women’s studies at Harvard Divinity School, and author of The People of the Parish: Community Life in a Late Medieval English Dioceses; Muriel McClendon was an assistant professor of history at the University of California, Los Angeles, and author of The Quiet Reformation: Magistrates and the Emergence of Protestantism in Tudor Norwich.

2. Katherine French, “Parochial Fund-Raising in Late Medieval Somerset,” in The Parish in English Life 1400–1600, ed. Katherine L. French, Gary G. Gibbs, and Beat A. Kümin (New York: Manchester University Press, 1997), 115–32; Katherine French, “‘To Free Them from Binding’: Women in the Late Medieval English Parish,” Journal of Interdisciplinary History 27, no. 3 (1997): 387–412; Katherine French, “Maidens’ Lights and Wives’ Stores: Women’s Parish Guilds in Late Medieval England,” Sixteenth Century Journal 29, no 2 (1998): 399–425.

3. Beth Allison Barr, The Pastoral Care of Women in Late Medieval England (Rochester, NY: Boydell: 2008), 14–15; French, “Parochial Fund-Raising,” 125–26; French, “Maidens’ Lights and Wives’ Stores,” 409.

4. Meeting minutes from First Baptist Elm Mott Ladies Aid society meeting, January 24, 1904, to July 25, 1910.

5. Muriel McClendon, The Quiet Reformation: Magistrates and the Emergence of Protestantism in Tudor Norwich (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1999), 6. McClendon, Quiet Reformation, 6; see also 2–7.

7. An allusion to Patrick Collinson’s classic study, The Birthpangs of Protestant England: Religious and Cultural Change in the Sixteenth and

Seventeenth Centuries (New York: Macmillan, 1988).

8. McClendon, Quiet Reformation, 7; see also 10–17.

9. McClendon, Quiet Reformation, 7; see also 10–17.

10. McClendon, Quiet Reformation, 17. 11. Personal correspondence, used with permission and edited for fluency.

12. Bob Smietana, “How God’s Pronouns and the CBMW Might Save Beth Allison Barr’s Church,” Religion News Service, November 11, 2021, https://religionnews.com/2021/11/11/how-gods-pronouns-and-the-cbmw-might-save-beth-allison-barrs-church/. 13. Personal correspondence, used with permission.