James Diddams recently published a piece at First Things provocatively entitled “The Real Problem at Wheaton College.” Diddams’s essay asserts that Wheaton College’s real problem is not liberal drift, as others have argued. Rather, the real issue is “few students care about or even understand the mission of Christian intellectual formation.” He continues: “Wheaton students tend to focus on practical career training and individual spirituality, giving little thought to how liberal learning can enhance one’s spiritual life or the importance of intellectual formation in the Christian tradition.”

The two fruits of this problem come as further critiques of Wheaton College. They are two: the school has a culture of careerism and ahistoricism. First, Diddams avers that Wheaton’s contituency, primarily students and parents, suffer from a careerist mentality. Careerism expects a person’s education to drive towards vocational training and professional success. Rather than appreciating the intrinsic good of learning and its inherent benefit to foster Christian and citizen virtues, careerism feeds individualist ambition and prioritizes personal gain over society’s good. While Diddams commended Wheaton College’s faculty for instructing students to read and understand great texts, he reproved them for failing to demonstrate why this practice is inherently beneficial. Diddams’s second critique is that Wheaton College has a culture of ahistoricism born from the “denominational indifference” of its constituents.

Provocatively entitled hit pieces, putting Wheaton College under public scrutiny, have become a novel bromide in the era of evangelical fragmentation. One past piece from First Things came from an institutional outsider, who excoriated Wheaton for “liberal drift” and “wokeness.” This piece was soundly redoubted by Vincent Bacote at Current. James Diddams’s piece is not like the other because it hails from an institutional insider, a recent graduate. Reproofs like this warrant more than callous dismissal. They ought to be heeded.

In what follows, I provide a reflection on the liberal arts, piety, and the past. Call this a token example of a counter narrative, where one faculty member attempts to push back against the encroachment of a careerist mentality and ahistoricism, real or perceived. This reflection is inspired from a lecture segment I offer to my students each semester at Wheaton College. In this teaching segment, I demonstrate the function of the argument I plan to make for a specific course, why it is meaningful for forming their character, and how the course equips them to be virtuous Christians and citizens. I revisit this segment and refresh it in their minds as the course concludes, forming a nice inclusio for the course.

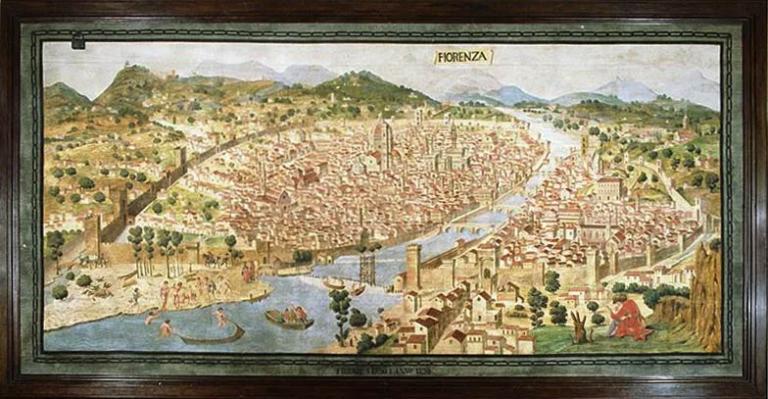

The lecture segment reminds students of how the renaissance leaders of Italy revived the study of the liberal arts. When I lecture on this material, I extol them to pursue learning both secular and sacred letters, and I admonish them to drink deeply from these letters their entire life.

In that lecture, I also share about my career trajectory. You see, I went to college and followed the careerist mindset. My undergraduate degree was a bachelor of business administration, with a focus in marketing. I pursued this first degree because it would make my parents proud, and it would have a practical function, in case vocational ministry did not work out for me. I did devote eight years to full-time vocational pastoral ministry, all the while integrating the practical learning I gained from my undergraduate degree in business. Nonetheless, in the lecture segment, I contend to students that I have received a greater reward from the habits of cultivating deep learning and the virtue formation drawn from studying the liberal arts, both secular and sacred.

Permit me to reiterate to you why the renaissance leaders of Italy recaptured and reignited a vision for the studia humanitatis (the study of the humanities). Perhaps, in some way, this exercise will help learners realize the inherent value in studying the liberal arts. This history testifies to the urgent need to be prepared in every season, for we know not what will befall us from one day to another (2 Tim. 4:2).

Liberal Arts and Piety

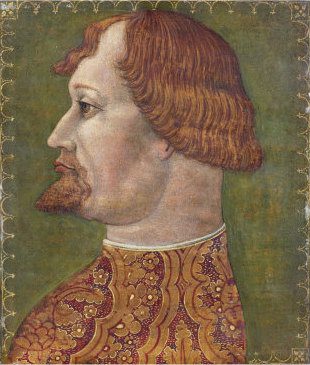

Leonardo Bruni and Caluccio Salutati reimagined citizenship in Florence, Italy after narrowly escaping destruction from the siege of Gian Galeazzo Visconti, Duke of Milan in 1402. During the siege, they stood upon the ramparts and looked upon both those who besieged them and their own citizens. They assessed how their citizenry managed the affair. They had barely hung on. Had it not been for the sudden death of the Duke of Milan, they might not have survived the siege.

You see, times of distress and anxiety test the moral fiber of citizens. Desperation causes rapid moral decay. For what value does temperance have in the face of hunger and thirst, fortitude in the face of famine, righteousness and justice in the face of rape and war? Well, those concerns bore down directly on Bruni and Salutati as they assessed the circumstances, and they vowed to reimagine for all their citizens how to cultivate the virtues of fortitude, temperance, justice, and prudence in the face of every circumstance.

Their new vision for citizenship relied on their mentor, Francesco Petrarch, who believed that citizens of liberty should reach back into the past and learn widely from Greek and Roman classical literature. Citizens of noble birth had the luxury and leisure to freely pursue a life of the mind. Inspiring these citizens to be models of this new view of citizenship was crucial to the program of Bruni and Salutati. They, too, must embody this vision for nobles to emulate. Thus, Bruni and Salutati developed a curriculum for the studia humanitatis, which set noble leaders on a path for success, the good life, and the flourishing of Florence. This became a pattern for every citizen to follow, for education is for every citizen, and its purpose is to create fruitfully productive and virtuous citizens. Perhaps, even here, with this premise, we may perceive the seedlings for the argument that the State ought to provide universal and fully funded collegiate education.

Pursuing the liberal arts was a pious devotion and an effort to produce virtue for those of noble character. They retrieved the thought of the pagan moral philosopher, Plato, who asserted this same argument in his work, Euthyphro, alongside the Cappadocian Father, Basil, who reiterated it in his letter “To Young Men.” Thus, the renaissance leaders of Florence recaptured and reignited the vision to equip every citizen for civic leadership and foster a system of education in the liberal arts that inculcated mastery of both sacred and secular letters.

Leonardo Bruni wrote a letter to Lady Batista Malatesta, which relied upon the scheme that St. Basil conveyed in his letter “To Young Men, On How They Might Derive Profit from Pagan Literature.” According to Basil, “Everything we do is by way of preparation for the other life” for “the soul is more precious than the body in all respects, so great is the difference between the two lives. Now to that other life the Holy Scriptures lead the way” (Basil, “To Young Men,” Loeb 270: 383). We also hear similar echoes of this thought in Aeneas Silvius Piccolomini’s letter to young Ladislas, King of Hungary (Piccolomini, “The Education of Boys,” I Tatti, 5: 126 ff.).

Basil knew that leaders, situated within the world, had to bring the truth of Scripture to bear on their context. He affirmed the importance of going to the “poets and writers of prose and orators and with all men from whom there is any prospect of benefit with reference to the care of our souls” (Basil, “To Young Men,” Loeb 270: 385). Leonardo Bruni reinforced Basil’s message by prioritizing the study of divinity, as the first order pursuit in the liberal arts, followed by moral philosophy (Bruni, “The Study of Literature,” I Tatti, 5: 94–95).

A Christian liberal arts education equips people with a mastery over both worlds of letters, the sacred and the secular. This offers them valuable tools to go into the world and lead from the fruits of their learning. Inhabiting a culture of grace, virtue, and excellence for a time of liberal study, across the broad spectrum of natural and social sciences, which beneficially prepares students to thrive in whatever profession they pursue. A broad liberal arts education brings people skills that translate well into multiple industries and vocations. Since it is rare for people to work in one role for their entire professional life, even if they remain at the same institution their entire career, a general instruction in liberal arts meaningfully prepares young women and men to engage in the regular practice of deep learning, which will benefit them, regardless what career they pursue.

This is one of the aspects of Wheaton College’s curriculum that I appreciate. Even if students pursue “careerist” degrees, they still receive a hearty liberal arts education. By design, students benefit from a broad liberal arts learning, which forms them to be productive and virtuous citizens. While other schools have retailored their programs and downgraded historical studies to one course in an undergraduate career, Wheaton has held on. Every student must take both a World history and an American history course.

Liberal Arts and the Past

Leonardo Bruni’s letter to Lady Batista highlighted the importance of history among the liberal arts. History stood of first importance to him after the study of divinity and moral philosophy. He said, “To the aforesaid subjects there should first be joined, in my view, a knowledge of history, which is a subject no scholar should neglect” (Bruni, “The Study of Literature,” I Tatti 5: 109). No doubt this is why Bruni wrote his History of the Florentine People (Cf. I Tatti Renaissance Library, Vols. 3, 16, 27).

The historical discipline provides a unique space to construct for students the history of interpreting Scripture, the history of the church in the world, and the history of human struggle and progress. Historical studies guide people to encounter all the sciences and arts from a historical vantage point and perceive trends across the long durée, flashpoints, turning points, and times of conflict and tension in human history. Historical studies look back to how the dead still speak to us, and they provide a toolkit and tools to address current circumstances.

Students may then learn the value of retrieving Leonardo Bruni’s letter to Lady Batista, which is a fifteenth century Italian Renaissance Christian’s argument, at the headwaters of the studia humanitatis, which champions women studying the liberal arts and pursuing civic leadership.

Listen to how Bruni frames the argument of his letter to Lady Batista as confirmation for his view:

I feel myself constrained, dear lady, by many successive reports of your wonderful virtues to write to you in commendation of the perfect development of those innate powers of which I have heard so much that is excellent, or, if that is too much, at least to urge you, through these literary efforts of mine, to bring them to such a perfection. There is, indeed, no lack of examples of women renowned for literary study and eloquence that I could mention to exhort you to excellence. Cornelia, the daughter of Scipio, wrote letters in the most elegant of styles, which letters survived for many centuries after her death. The poetical works of Sappho were held in the highest honor among the Greeks for their unique eloquence and literary skill. Then, too, there was Aspasia, a learned lady of the time of Socrates, who was outstanding in eloquence and literature, and from whom even so great a philosopher as Socrates did not blush to admit he had learned certain things. I could mention still others, but let these three stand sufficient as example of the most renowned women. Be encouraged and elevated by their excellence! (Bruni, “The Study of Literature,” I Tatti, 5: 93).

This is a solitary, concrete example of how historical studies retrieve and revive the past, as well as revise our understanding of it, for the benefit of those in the present. In this particular instance, Bruni’s letter to Lady Batista conveys to women the noble role they may fulfill as thinkers and leaders of a free society. This fifteenth century letter will seem revolutionary, even now, for many who inhabit a patriarchal worldview.

Revision for Revival

There are many aspects of our current construction of Christian culture and society that need to be revisited and revised in light of what we have learned from the past. Fostering the life of the mind for young Christian intellectuals and professionals, who will go out into the world and shape it as leaders, is a calling that faculty should take seriously at Christian colleges and universities. They should do all they may to help students discover the value of deep learning in the liberal arts, and they should inspire them to pursue this learning all their life.

The revival of the liberal arts, as a revision for producing flourishing life in the coming twenty-first century, is only one component of the kind of revival needed for a just, global society and culture. As urgently as we must reappropriate and reawaken an affection for the liberal arts, our society needs a spiritual renewal as well. I believe Wheaton College, as one among many colleges and universities, is strategically positioned to offer both kinds of renewal for global citizens.