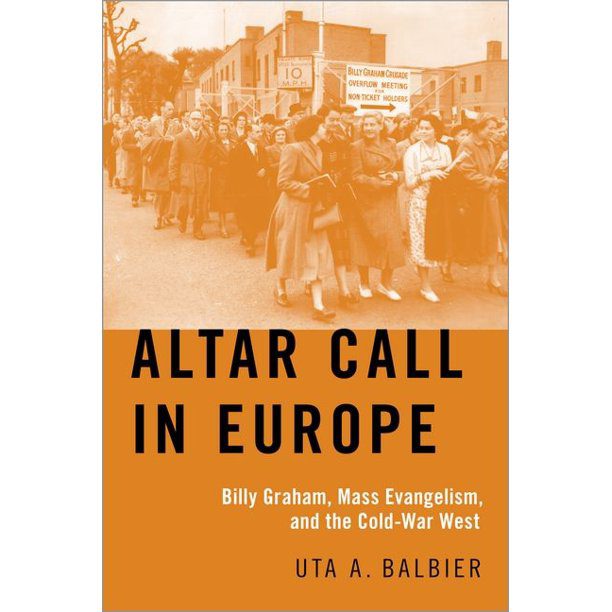

I’m pleased to welcome Uta Balbier to the Anxious Bench. She is Associate Professor of Twentieth-Century North American History at the University of Oxford and is the author of the just-released Altar Call in Europe: Billy Graham, Mass Evangelism, and the Cold-War West. What follows is a conversation we recently had about transnational evangelicalism in the 1950s. –David

***

David: What led you to this topic of Billy Graham’s evangelistic crusades in the United Kingdom and Germany?

Uta: Well, the topic certainly found me! I had been interested in the complex history of American Evangelicalism for a while when my research took me to the Billy Graham Center Archives for the first time. Billy Graham seemed the perfect focus for a study on how US evangelicalism embraced modern media culture, Cold War patriotism, and consumer capitalism; a development which I had always perceived as “exceptionally” American. When one of the archivists introduced me to Graham’s successful work in England and Germany in the 1950s, I saw many of my national perceptions challenged and several questions sprang up: why do we tend to see Graham as a unique American success story, when he was so successful outside of the American context? And why has his work been mainly overlooked in the religious histories of Germany and Britain? And why do we hear so little about what his success in Europe has meant for Graham’s impact in the US?

Billy Graham and other American evangelicals invested a lot of time and money in Europe in the 1950s. Why there and then?

Billy Graham and other American evangelicals invested a lot of time and money in Europe in the 1950s. Why there and then?

Today, Europe is a predominantly secular continent, but that is not how American evangelicals perceived it in the 1950s. Germans and Britons flocked to their churches in the direct aftermath of World War II where they searched for spiritual comfort amidst hunger and destruction. Government and church officials in Germany, England and the US saw Christianity as the moral grounding for future peace and flourishing democracies. American evangelicals clearly saw this shared belief in re-Christianization as an invitation and motivation to go to Europe. And they shared with many of their European counterparts the firm belief that Christianity was the only force which could face off Communism, which they saw as a real ideological and military threat to what evangelicals perceived as the Free World.

A correspondent with Time magazine observed at a 1954 evangelistic crusade in London that Graham “slowed down his usual machine-gun delivery for the benefit of British ears and moderated his usual platform prowl in deference to British dignity.” In what other ways did he adjust to European contexts?

Definitely with regard to music. The local organising teams were keen to see the local musical religious traditions brought to life during the revival meetings: the Germans stuck with their trombones and the quintessential Protestant hymn “Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott”, while the British turned the rousing Welsh Cwm Rhondda into the signature hymn of the twelve-weeks-long Harringay revival meeting in 1954. Other considerations were made regarding the use of the hymn “Just as I am without one Plea” during the Altar Call. Because many Europeans considered it too emotional, Graham agreed to drop it at some of the revival meetings in England and Germany. I haven’t looked into this in full detail, but I would also be surprised if Graham preached with a similar apocalyptic subtext when in Europe. Because of the strong pre-millennial tradition in US evangelicalism, Graham often evoked images of nuclear destruction, war, and unrest to signal that the end-times were about to start. He did that to some degree in London but certainly not as pronounced as in New York or LA.

Graham’s successes (in terms of drawing numbers and generating interest) took place in an era of profound secularization. How did he do so well?

When one listens to the voices of the thousands of people who organized and attended Graham’s revival meetings in London and Berlin, for those Christians secularization in 1954 was not at all a done deal. There was a strong re-Christianization drive after the Second World War, as I already described, and for many Europeans Graham appeared as the knight in shining armour in the fight against secularization: he offered what organisers and participants called a “modern faith” which did not take shape in opposition to modern life, but by embracing it. Thus, Graham was able to answer some very profound questions for European Christians regarding the interplay between consumerism, Cold War culture, and religion, as well as how religiosity could be lived and experienced in an increasing media- and entertainment-driven culture. And of course, the ability of the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association to fundraise and pull off impressive marketing campaigns also played a role.

I found your chapter on “Living Religion,” especially the material on prayer, to be utterly fascinating. You show how Graham delegated prayer “in a secular and businesslike manner.” What did that look like, and how was that received by Europeans?

I loved writing that chapter! Even though many in Europe criticized Graham as a light form of religious entertainment, and we hear some similar voices in the US, when one looks at the religious practices of those planning, preparing and attending the revival meetings, one can easily trace their profound spiritual relevance. Prayer is the perfect lens through which we can observe how for Graham traditional spiritual practices and modern means were never mutually exclusive: Graham asked for prayer for the campaigns, because he deeply believed in the transformative power of prayer in the most traditional Christian sense. This, however, did not prevent the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association in cooperation with the local organising teams to create a prayer support network, bureaucratically broken down in specific local, regional, and national districts with clearly assigned leadership roles. Communication between the different prayer units was organized through centrally published prayer newsletters which made sure that every prayer meeting followed the same rules or took place at the same time. This meant, for instance, that when Graham made the Altar Call at Harringay Arena in London, thousands around the world joined spiritually in prayer for that very moment. And Europeans joined these prayer groups and chains enthusiastically because they held less rigid assumptions about what was considered “secular” versus “religious” than their church leadership often did.

How were the shared spaces of buses so significant in the United Kingdom and Germany?

One of the main themes of the book is how people of faith imagined and lived what they called a more “modern faith” that combined traditional religious practices with their modern lifestyles and surroundings. The buses captured that ambition beautifully: organised bus travel to the revival meetings was born out of the necessity of modern transport within metropolitan centers which the organisers seamlessly combined with very traditional religious practices such as praying and singing, thus turning them into a distinctively 20th century form of pilgrimage.

Operation Andrew used chartered buses to transport unchurched acquaintances to crusades. Why did Graham’s people insist on buses despite the availability of efficient public transportation systems?

The main challenge for the local organizers was to make sure that those who found Christ at one of the large revival meetings would find a home in one of the local churches. The decision card system, through which data of those who answered the altar call was collected at the end of the revival meetings, was one way of accomplishing this. But organising joint travel on a bus for the “unchurched” was of course a much more personal way of introducing prospective people of faith to a potential local religious home. And as I said before, these joint bus rides were beautifully crafted pilgrimages as one newspaper observed: the mission starts on the bus. And the buses were also really important spiritual spaces to counter the mass character of the main meeting: it was on these buses where personal and spiritual connections were being forged.

You quote historian Callum Brown: “Despite the millions attending, Graham’s work did nothing to arrest the imminent commencement of rapid secularisation.” Could you briefly describe the causes of secularization in Europe?

Well, according to Callum Brown, women stopped going to church! And he is right of course: with women increasingly finding ways to gain personal fulfilment through work outside the house, many churches lost their backbone. And of course a new generation which came of age during the 1960s very vocally challenged social and cultural norms associated with the churches. But there is another reason why churches were emptying in England and Germany: in the 1960s, even leading Protestants complained publicly about the “rustiness” of their churches, their inability to make their offer more attractive. And Graham’s role in the 1950s in England and in Germany was to demonstrate that people could be attracted to faith in many different ways: through screenings of religious movies such as “Oiltown U.S.A.”, through Cowboy shows for children, through powerful musical entertainment, and through modern mass marketing. People in Germany and England, like in the United States, lived in modern consumer and media cultures. They were looking for a faith and for spiritual offers which were compatible with these cultures. Even though thousands attended the Billy Graham crusades in Germany and the UK, especially the established churches dismissed this demand, and this the ground for their increasing loss in membership.

You write, “Maybe God was not quite dead in 1966, but the transatlantic Cold War revival certainly was.” How was Graham out of step with European mores in the 1960s?

Even though I argue in the book for similar religious phenomena occurring in the 1950s tying the British, German, and US religious landscapes closely together, it is undeniably the case that these landscapes developed increasingly differently since the late 1950s: while the US one developed along the lines of rapid modernization displaying a striking dynamic, the European one was captured by secularization. Because of emptying churches, Graham could no longer rely on strong local support which was key to the success of his revival meetings. But it was also the case that the theological debates in the German and British churches gained in fervor. Important and widely read books, such as British theologian John Robinson’s “Honest to God”, raised questions about the very nature of faith that Graham’s rather stern fundamentalism could no longer engage with. While Graham was able to connect to crucial debates about ecumenism, religious change, and political challenges in the 1950s, he was quite lost in the European world of the 1960s which was marked by sexual liberation and female emancipation. In the US, he was still able to rely on a large conservative evangelical support base, but that never really existed in similar size in Germany or the UK. And there was, of course, the long shadow of the Vietnam War, which Graham was supportive of, which loomed large over him as the vast majority of Germany and British people of faith opposed it.

We know each other from a transatlantic group that researches the global history of American evangelicalism. Based on these interactions—and your extensive reading in this field—what differences do you see in the ways Americans and Europeans practice the historical craft?

That research group was certainly one of the most stimulating intellectual experiences of my career! I find it incredibly striking how much historians of religion on both sides of the Atlantic are shaped by the religious landscapes they live in. The dynamic existing religious landscape of the US (with all its flaws!) seemed to have inspired a form of religious historical writing which is very much focused on individual faith, the practices of lived religion, and the possible fruitful intersections between religion and modern life. On the other hand, I sense that especially historians of Modern Europe based in Europe write religious histories which are much more marked by a narrative of secular doom and loss. There is also a clear emphasis on research on churches as the administrative units of religious life. That is also a reason why Graham’s revival meetings in Germany and the UK have been mostly overlooked by German and British religious historians: they are forms of lived religion which sometimes intersect with, but which sometimes also counter, church histories.

What are you working on now?

Your very own fantastic work on the transnational ties between US evangelicals and the Global South inspired me to look further into Graham’s first revival tour through Africa in 1960. The fact that many British missionaries were involved in organizing the revival meetings, for example in Nigeria, led me to look into another set of complex transnational connections: that between US evangelists, British missionaries, and local Nigerian Christians. It raises fascinating questions about different concepts of Empire and their intersections with Christianity competing on the ground in Nigeria, at the crucial time of decolonization and national independence. I see this smaller project as a step towards a larger research project on the transnational connections between US, UK and Nigerian Evangelicalism and Pentecostalism and how this transnational connectedness shapes their imperial, economic, and spiritual nature. With the rise of Pentecostal Christianity as a crucial political player in communities around the world, this project aims not just to inform academic, but also broader public and political debates.