On the 10th of February, 1675/6, natives allied with the Wampanoag leader, King Philip (Metacom), attacked the village of Lancaster and besieged the home of the town minister, Joseph Rowlandson. This was one of a dozen raids that entirely razed whole British colonial townships during the terrifying King Philip’s War. Fundamentally, this war was an attempt, by a league of native tribes, to reclaim the wilderness from the British who had been domesticating and subduing it. The natives’ chief aim was to wipe out any and all signs of British colonial civilization.

After two hours, the natives raiding upon Lancaster set fire to many of the homes, including the home of Joseph Rowlandson. All who sought refuge in his home were forced to flee the danger of smoke inhalation. What was once a safe and warm refuge from the wilderness without had now become a fiery furnace and inferno. With no other alternative, the colonists left the confines of the home and entered into the thick of native gunfire and hand-to-hand combat.

When Mary Rowlandson crossed the threshold of her home’s doorway and entered into the dangerous onslaught from wilderness natives, a bullet struck her through her side, tearing through the gut of her child she carried on her hip. The natives took her captive and removed her from her safe, civilized New England village.

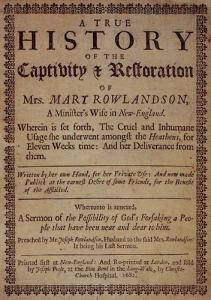

Over the course of the next eleven weeks, she was forcibly marched through the wilderness with the natives, as they sought to ransom her for a pleasing price. Her story, A True History of the Captivity and Restoration of Mary Rowlandson, a Minister’s Wife in New England (1682), recounted twenty removes.

For the first three removes, she carried her wounded child with her. The natives kept threatening that they’d knock her child on the head to end his suffering, but these threats came to an end on the ninth day when he passed in her arms from the wounds he suffered. Her child was six years old. The natives buried her child outside the Indian town on a hill. When she visited the place she said: “There I left that child in the wilderness, and must commit it, and myself also in this wilderness condition, to him who is above all” (Rowlandson, 6).

In the wilderness with her captors, Mrs. Rowlandson survived. Her side wound must have been a glancing or grazing wound. If it had been mortal, the natives would have knocked her on the head. Since she was the wife of a minister, she was esteemed as valuable and worth keeping alive. Mary applied oaken leaves from the wilderness to her wound. She claimed: “…with the blessing of God it cured me.” This remedy was recommended to her by Robert Pepper, another captive taken from Roxbury. Whether this was a folkloric wilderness remedy learned from the natives or not, these British Puritan colonists credited the Christian God for their comfort and healing in the wilderness.

Her master and mistress constantly mistreated her during the many removes in the wilderness. They kept her from the warmth and fire within the wigwam by putting her out from it to sleep in the cold and snow. They barely gave her any sustenance. She scrounged for ground nuts and gained scraps from generous natives. Once one made her a pancake from wheat fried in bear grease. Another time she begged for a horse liver, which she attempted to heat on coals. But the natives took half of it from her. She fought to keep the uncooked half and furiously ate it raw. Another time she was given a scrap of meat from a fawn. This proper, domesticated woman, who had sometimes wasted food or took its plentitude for granted, became near savage, herself, to survive on what she foraged from the wilderness.

Though Mrs. Rowlandson went into the wilderness with next to nothing, tokens from civilization graced her captivity. A native with plunder from the Medfield raid offered her a Bible, which she gladly accepted. She immediately took this prize and read the first 28 chapters of Deuteronomy, permitting the curses that conclude chapter 28 to haunt her downcast soul. From then on, her recount of the removes throughout the wilderness were punctuated with Scriptures that comforted her during her journey.

On one occasion, heart aching thoughts of her children, “scattered among the wild beasts of the forest,” directed her mind toward Scripture. Though she was starving, sleep-deprived, sore and feeble from hard travel and terrible lodging conditions, “the Lord helped me at that time to express it to himself. I opened my Bible to read, and the Lord brought that precious Scripture to me, Jer. 31:16” (Rowlandson, 8) Though she couldn’t escape her savage circumstances in the wilderness or physically protect her children from wilderness threats, she could retreat into the spiritual fortitude of the Word and request spiritual protection for her children.

Frequently, in the throes of deep discouragement, Rowlandson wandered deep into the wilderness to collect sticks, and, with her bible in tow, she retreated deep into her inner life, calling upon Scripture from that bible to offer her comfort. On one occasion, she recalled:

So that my Spirit was now quite ready to sink. I asked them to let me go out, and pick up some sticks that I might get alone, and pour out my heart unto the Lord. Then also I took my Bible to read… Afterward , before this doleful time ended with me, I was turning the leaves of my Bible, and the Lord brought to me some Scriptures, which did a little revive me. (Rowlandson, 16)

The printed text and her exercise of reading it reminded her that a civilized domain existed beyond the wilderness. She had not yet lost her way and become savage herself. She might yet hope to return to civilization and to reclaim her role in the domain of domesticity.

Her other token from civilization was her knitting works, key symbols and remnants of the domestic realm from which she so suddenly had been removed. These she used to make knit goods for natives. In a dramatic reversal, Mrs. Rowlandson brought domesticity and civilized textiles into the wilderness and clothed her captors with them. Her industrious work led to exchanges for other items, many of which were confiscated by her cruel master and mistress.

During her wilderness wandering, God answered her prayers, and she reunited with her ten year old daughter, Mary, and her son, Joseph. While she did not get to travel with her children, on occasion, she did have the freedom to visit them. The natives kept captives, particularly family members, isolated from one another. Colonists like Mrs. Rowlandson and her children were considered valuable assets, especially worthwhile for ransom.

The natives knew how to identify leading families in New England communities, and they had long known that ministers and their families were prominent figures in the community. Ultimately, Mary would be exchanged for the price of £20.

After eleven weeks and twenty removals, Mrs. Rowlandson returned to her civilized life of domesticity. Towards the end of her captivity narrative, she noted: “Thus hath the Lord brought me and mine out of that horrible pit, and hath set us in the midst of tender-hearted and compassionate Christians” (Rowlandson, 32).

Throughout this history, a certain bias against natives, their wilderness ways, and how they treated their captives emerges. In distinct contrast to how poorly she was mistreated by her master and mistress among the natives, Mrs. Rowlandson concludes her history by describing the sort of hospitality and welcome she received from her Puritan New England co-belligerents, who had narrowly survived the ordeal of King Philip’s War.

Upon her return to civilization, Christians throughout New England demonstrated their Christian charity and compassion by providing generous gifts to help the Rowlandson family reclaim the domestic geography so critical and symbolic to their safety and flourishing, a British style home in a British colonial village.

I thought it somewhat strange to set up House-keeping with bare walls, but, as Soloman says, Money answers all things: and that we had through the benevolence of Christian friends, some in this Town, and some in that, and others, and some from England, that in a little time we might look, and see the house furnished with love. (Rowlandson, 33)

The news of her terrible ordeal certainly circulated by mouth throughout colonial New England, and, no doubt, the publication of A True History of the Captivity and Restoration of Mary Rowlandson, a Minister’s Wife in New England must have contributed to promoting her and Joseph’s great need to re-establish themselves in British colonial society. For Mrs. Rowlandson, she wasn’t altogether delivered from the wilderness and captivity until her restoration and return to a British style home, where she could quietly sit by her hearth and read her bible to her children.

In the wilderness, Rowlandson perceived the natives and their way of life to be impoverished and difficult. She repeatedly commented on the scarcity of food for both the natives and herself. The natives had so very little that even she, a captive, was able to build a little textile cottage industry to uplift herself during her trial and affliction. In contrast, British Puritans had an abundance of goods and generous and charitable spirits.

While it is clear that British civilization and colonial domesticity was perceived by Mrs. Rowlandson to be a superior way of life to that of the natives in the wilderness, she also came away from her ordeal with a deeper understanding of how fickle and fleeting the comforts of this world are, especially to those who live on the vulnerable margins of the British Empire.

She concluded:

The Lord hath shewed me the vanity of these outward things, that they are the Vanity of vanities, and vexation of spirit, that they are but a shadow, a blast, a bubble, and things of no continuance, that we must rely on God himself, and our whole dependance must be upon him. (Rowlandson, 36).