![]() Zaccheus was a wee little man. We sang that loud and proud in Sunday school when I was young. We had no idea who Zaccheus was, but we loved getting to sing a song that made fun of a short guy. Jesus may have been his friend, but we still got to call him Shorty.

Zaccheus was a wee little man. We sang that loud and proud in Sunday school when I was young. We had no idea who Zaccheus was, but we loved getting to sing a song that made fun of a short guy. Jesus may have been his friend, but we still got to call him Shorty.

We weren’t bullying anyone exactly, and we were children so we were all short. But the lesson, for those who didn’t grow tall and for the rest of us, was there. Bullying, which is such a social problem in our time and in our schools, begins with something simple like that. And gets taken to extremes by some who feed on the pleasure of putting someone else down.

Zaccheus must have been remarkably short, for Luke to have written down that detail about him. It seems he was a first century scapegoat, the guy everyone got to pick on. And that may be why he became a tax collector for the Roman Empire. As Caesar’s tax collector, he finally got some respect, even if it was the grudging kind. People detested paying Roman taxes, but Zaccheus had Roman soldiers to back him up, so no one was going to be surly, or beat him up when he came around, because he could send in the henchmen.

Tax collectors then generally had a reputation for pocketing a sizeable amount of what they collected. It was one of the perks of the job, to add on a hefty surtax for yourself. So when Jesus came to Zaccheus’ house for lunch that day, which was pretty hard for the townspeople to watch Jesus do, Zaccheus piped right up, saying he never cheated folks, and if he had he would repay them four fold. And, he said, he tithed forty percent of what he earned. And Jesus believed him. Jesus said salvation had come to his house.

Tax collectors then generally had a reputation for pocketing a sizeable amount of what they collected. It was one of the perks of the job, to add on a hefty surtax for yourself. So when Jesus came to Zaccheus’ house for lunch that day, which was pretty hard for the townspeople to watch Jesus do, Zaccheus piped right up, saying he never cheated folks, and if he had he would repay them four fold. And, he said, he tithed forty percent of what he earned. And Jesus believed him. Jesus said salvation had come to his house.

Saints are people who are windows in this world. The light of God shines through them so brightly that people say they have seen salvation in them, and in the household of their lives. A remarkable thing about them is that many were scapegoats early in their lives, bullied and called contemptible by folks around them. To mention a few:

St. Francis of Assisi’s father dragged him into court in the town square, enraged because his son had secretly arranged to steal his father’s valuable assets, and given them to monks to sell for support of the poor. He was found guilty. Then, as a monk himself, he angered the local bishops by creating his own liturgies, including animals in his congregation.

St. Francis of Assisi’s father dragged him into court in the town square, enraged because his son had secretly arranged to steal his father’s valuable assets, and given them to monks to sell for support of the poor. He was found guilty. Then, as a monk himself, he angered the local bishops by creating his own liturgies, including animals in his congregation.

St. Teresa of Avila was considered a nut and way too outspoken for a woman, and shocking in her opinons.

Juliana of Norwich lost her entire family to the plague, and had visions so extraordinary no one knew what to make of them.

Mother Teresa expressed her strong doubts about God, in writing. And became a nun to escape life in her small town in Skopje, Macedonia.

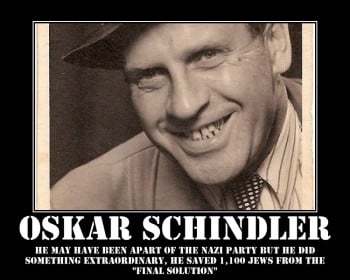

Oskar Schindler, who saved Jews from death in World War II Germany, was a Nazi, womanizer and a drunk, who used his popular and deserved reputation as a scoundrel as a cover for what he was doing.

Oskar Schindler, who saved Jews from death in World War II Germany, was a Nazi, womanizer and a drunk, who used his popular and deserved reputation as a scoundrel as a cover for what he was doing.

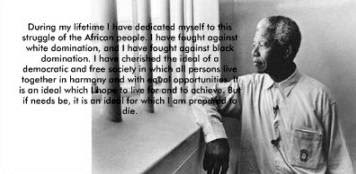

Nelson Mandela was considered a public enemy by the government of South Africa, which put him in jail for 27 years, during all of which he was a beacon of hope for black South Africans.

Like Zaccheus, these saints, and so many others, flouted public conventions in ways that were painful for them, but also allowed them to let God’s light into this world.

Jesus, in the stories the lectionary has given for the past several weeks, has held up people most folks found repulsive – lost sheep, prodigal sons, the lame, the lepers, the dishonest steward, the repugnant poor man lying in a stupor covered with sores, and for two weeks now, dislikeable tax collectors, urging us to look into them and discover their saintly light.

Most of us, and I include myself, prefer our saints to be heroic. We edit their stories to the nub of their heroism. We tell ourselves that athletes can be our heroes, or decorated soldiers, dancing movie stars, the beautiful and the well-dressed.

We love Mandela washed and in a suit. In his prison garb, and with educated South African whites warning us of his dangerousness, he was alarming to white Christians. Mother Teresa’s honest writings have been alarming to many devout Catholics. And Francis of Assisi, in his lifetime, was alarming to Bishops.

We love Mandela washed and in a suit. In his prison garb, and with educated South African whites warning us of his dangerousness, he was alarming to white Christians. Mother Teresa’s honest writings have been alarming to many devout Catholics. And Francis of Assisi, in his lifetime, was alarming to Bishops.

Most of us are aware of the tragedies wrought by bullies among those who succumb to their humiliation and mistreatment. The young, who are often bullied for being gay, or un-athletic, different, foreign, members of other faiths, socially inept, unattractive, are too often driven to despair by this.

What Jesus treasures in the despised is their ability to hang on, to survive with a part of their own humanity intact despite the way they have been treated by the world. This part of themselves becomes their shining light, becomes the window of their soul and a lighted path for all our souls.

And by choosing no others to hold up to us than these, who have been despised and for long, Jesus is teaching that the saints do not come into this world apart from their suffering. Nor will we be able to find the light of God in our own lives, apart from ours. For the saints are not among us to show us the way into easy, comfortable lives. They are here to show us how to keep going in deep darkness, how to survive the bullies, how to have hope in mean times.

And by choosing no others to hold up to us than these, who have been despised and for long, Jesus is teaching that the saints do not come into this world apart from their suffering. Nor will we be able to find the light of God in our own lives, apart from ours. For the saints are not among us to show us the way into easy, comfortable lives. They are here to show us how to keep going in deep darkness, how to survive the bullies, how to have hope in mean times.

No wonder, then, that we celebrate the saints in the dark of the year, a time they understand well, a darkness in which they shine.

_______________________________________________

Illustrations:

1. Zaccheus Icon. Only found on Christ the Savior Orthodox Church site, christhesavioroca,org.

2. Zaccheus CD Cover, Google Images.

3. St. Francis, by Brother Eric. 20th c. Church of Reconciliation, Taize, France. Vanderbilt Divinity school Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.

4. Oskar Schindler, poster.

5. Nelson Mandela in Prison, poster.

6. Going Out on a Limb. Google Images.

7. Zaccheus. Image only found on Rich Brown’s ForeWords blog post for All Saints Day.