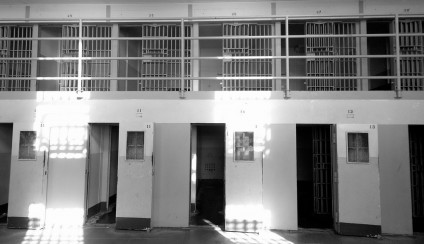

William Barnwell, an Episcopal priest who lives in New Orleans, has spent his life working for racial justice and reconciliation, mostly in the south but for about ten years in Boston, which is when we became friends. In retirement, he is choosing to spend his time volunteering in Louisiana’s infamous Angola maximum security prison, where men convicted of violent acts are locked away, often for decades. The majority of the prisoners are black.

William Barnwell, an Episcopal priest who lives in New Orleans, has spent his life working for racial justice and reconciliation, mostly in the south but for about ten years in Boston, which is when we became friends. In retirement, he is choosing to spend his time volunteering in Louisiana’s infamous Angola maximum security prison, where men convicted of violent acts are locked away, often for decades. The majority of the prisoners are black.

Barnwell runs a different kind of Bible study there, guiding the men in conversations about their own lives, framing his questions from stories about Jesus’ life. When Jesus began his ministry he had just been plunged into a wilderness, Barnwell will say to men who have been plunged from a tropical southern environment into a vast, barren, cement world. What are your wilderness experiences?And he will go on: Jesus was subjected to temptations? What temptations torment you?And, who are the angels who have ministered to you?

Sessions run four hours long, and over time Barnwell says he has seen hardened haters, white men with swastika and KKK tattoos, and black men with tattoos of violent gangs, begin to call each other friends. The stories they tell are not easy to hear. But Barnwell insists they are holy stories, because they are genuine stories in which faith is found, and hard-won, in the wilderness. This is our treasure, Barnwell says, our own stories of our lives.

Sessions run four hours long, and over time Barnwell says he has seen hardened haters, white men with swastika and KKK tattoos, and black men with tattoos of violent gangs, begin to call each other friends. The stories they tell are not easy to hear. But Barnwell insists they are holy stories, because they are genuine stories in which faith is found, and hard-won, in the wilderness. This is our treasure, Barnwell says, our own stories of our lives.

Jesus asserts this truth to Peter, in Mark’s 8th chapter, while they are walking along. He asks his followers what names people are calling him, and they tell him quite a number of names, and he asks them who they say he is, and Peter blurts, Messiah! And Jesus tells him to quit saying that in public.

Why? Because it might be dangerous for him? Because he wants to wait till later to reveal that? Because he’s meek and humble and finds it embarrassing? None of these reasons hold water: Jesus walks ahead of them into danger and confrontation, not just in Jerusalem, but in every sermon, every town, a number of which he is thrown out of. And at the end of this passage he is urging them to understand that taking risks is part of being his follower. Nothing ever embarrasses him, not hanging around with prostitutes, not dining with rich men, not being crucified, so it does not make sense that he would cringe from the name Messiah as if it were unseemly. Waiting for the right time is a Markan theme for Jesus, yet in the entirety of this passage it does not seem a good fit, as he moves them away from cautious protection and toward cross-bearing.

![]() Perhaps he is pushing aside the name Messiah here, because it stops the conversation. It stops the story-telling. What more is there to say, after Messiah? And Jesus wants people to wrestle with who he is to them, wants them to wrestle with their own lives and the presence of the kingdom in their lives.

Perhaps he is pushing aside the name Messiah here, because it stops the conversation. It stops the story-telling. What more is there to say, after Messiah? And Jesus wants people to wrestle with who he is to them, wants them to wrestle with their own lives and the presence of the kingdom in their lives.

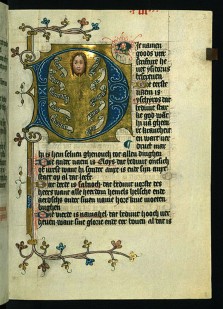

Jesus prefers the testimony of living experience to the rote recitation of meaning. This has been his consistent approach to worshipful life, according to the gospels, in which he chides the prayer-book reciting Pharisee and praises the awkward prayer of the publican, in which he resists Sabbath pieties and all pieties, in favor of mercies given and received. And yet, for most churchgoing Christians, the answer to who Jesus is has been removed from their experience and assigned to an ancient creed, usually the Nicene (325 CE) or Apostles (390CE) creed, both of which contain sets of approved names and defined divinity.

Yes, the creeds are treasures of our history, as are the many more contemporary statements of faith. But they have the effect of leaving us speechless, when asked, Who do you say he is? The answer I commonly hear is, I don’t know what I believe, really.Which is an admission that the creeds don’t speak for people, but for institutions and for the past. Most Christians say them in worship as something-you-do, and leave it at that.

Yes, the creeds are treasures of our history, as are the many more contemporary statements of faith. But they have the effect of leaving us speechless, when asked, Who do you say he is? The answer I commonly hear is, I don’t know what I believe, really.Which is an admission that the creeds don’t speak for people, but for institutions and for the past. Most Christians say them in worship as something-you-do, and leave it at that.

After hushing Peter’s show-stopping name Messiah, a name of glory, Jesus begins to talk about imminent danger. And Peter, who has just hailed Jesus with a triumphant name, begins to resist, urging cautious self-protection. Jesus then calls him Satan, stating emphatically that no one who will not pick up the cross can rightly claim to be a follower of Jesus. Saying, you are setting your mind on human things, not divine things. As we all do, as our churches do, setting our minds on Fairs and Feast Days, not on proclamations that lead to crucifixions. Saying the name Messiah isn’t enough, you have to walk the walk.

![]() Creeds, those 4th century Pledges of Allegiance, are not something I am willing to die for. And the history of Christianity holds more examples of those who died trying to give a more personal, and in some ways alternate, testimony, and who were executed by the Avenging Conformity Enforcers, than it does of those who died for the sake of the Creed.

Creeds, those 4th century Pledges of Allegiance, are not something I am willing to die for. And the history of Christianity holds more examples of those who died trying to give a more personal, and in some ways alternate, testimony, and who were executed by the Avenging Conformity Enforcers, than it does of those who died for the sake of the Creed.

Conformity of thought is an impoverished substitute for a heartfelt story, and Jesus knew that. In Angola State Prison, wronged and wrongful men know it, too, thanks to the ministry of an Episcopal priest, who, in his own recitations of the Creed, bows his head for the words, he has spoken through the prophets.

Mark 8 ends the story of names with Jesus saying, If they’re ashamed of me now, wait till the resurrection – they’ll still be ashamed of me. We would do well to stand in trembling before the awful unknown of what and who will rise, at last.

_________________________________________________________

Illustrations:

1. Angola, Louisiana State Prison, Google Images.

2. Angola, aerial view, 2011 AP Photo by Patrick Semansky, Google Images.

3. Holy Trinity and Ten Names of God Icon. 1404. Dirc von Delf. Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, MD

4. Holy Trinity Icon. Andrei Rublev. 1400. Moscow Russia. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.

5. Holy Trinity carving, Poland. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.

6. Eastern Orthodox Icon of Jesus as the True Vine, 16th c. Athens, Greece. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.