‘Beware of practicing your piety before others in order to be seen by them; for then you have no reward from your Father in heaven’ – Jesus, in Matthew 6: 1

‘Beware of practicing your piety before others in order to be seen by them; for then you have no reward from your Father in heaven’ – Jesus, in Matthew 6: 1

Piety, according to Webster, is the quality of being dutiful in religion. Or, an act inspired by dutifulness in religion. Or, a conventional belief or standard.

Jesus, suspicious of piety, urges something different in us. Lent will unfold with stories of him upbraiding the pious and bestowing incredible blessings on those who have failed miserably, in public, at conventional standards. Failed at piety, that is.

Yet Ash Wednesday, the doorway to Lent, is a day of public piety, of conventional rites embraced by many. If your ties are to liturgical traditions, you will get your forehead smudged with ashes by a priest and receive the personal admonition to remember that you are dust and to dust you shall return. And you give up something you like a lot, till Easter comes. If your ties are mainline, reformed, evangelical or Pentecostal, you may not go to church on this day, but you will take on some extra Lenten obligation, works of goodness toward your family or toward the needy, and some kind of Mite Box financial pledge.

All of this is piety. And Jesus is wary of piety, wary of what we are actually up to, wary that we are trying to fool God, and ourselves, too, about who God loves.

She’s a good girl, she loves her mama, loves Jesus, and America too . . . -lyrics from Free Falling, by Tom Petty

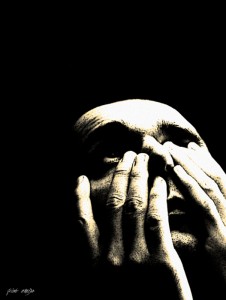

There are so many ways in which we are all pious. Piety is a sack full of shoulds, and many of us carry quite a load. We know what to do, to be acceptable in our world, to curry favor with others, to make ourselves look good – to keep ourselves from being in Free Fall, the abyss in which only trust can save us from the unknown.

Piety is a fiction we invent, to tell ourselves that we are safe, and to convince others they are safe with us. None of our pious acts is wrong, exactly, but the sum of them is wrong inexactly, wrong because our piety lacks integrity: it is focused on ourselves (if we please God, Jesus, the neighbors, mom, dad, then they will . . . think well of us and do what we want . . . be glad we are the people they wanted . . . love us . . .) and wrong because the fullness of who we really are, the range of desires, sins, and amazing virtue, can be completely hidden behind the facade of our pieties.

Piety is a fiction we invent, to tell ourselves that we are safe, and to convince others they are safe with us. None of our pious acts is wrong, exactly, but the sum of them is wrong inexactly, wrong because our piety lacks integrity: it is focused on ourselves (if we please God, Jesus, the neighbors, mom, dad, then they will . . . think well of us and do what we want . . . be glad we are the people they wanted . . . love us . . .) and wrong because the fullness of who we really are, the range of desires, sins, and amazing virtue, can be completely hidden behind the facade of our pieties.

It can be hard to even find our rage about Jesus’ challenge to piety. And just why should that woman at the well who has had five husbands get the first cup of eternal life, while Nicodemus, who checked off every box on the righteous to-do list, got a reprimand? Sometimes it makes me so angry that I don’t earn the points I think I deserve for my good behavior.

It’s our shoulds that Jesus mistrusts in us. Going through the Gate into Lent takes us into free fall. The Gate marks the divide between the world of propriety, where we know the rules and the consequences, and feel safer seeing lawbreakers punished and model citizens rewarded, and the world of chaos, where we have no idea what will happen next, or where we will end up, or even where there is to go. Smudged or unsmudged, we all have to go through that Gate, and not just for an hour in church.

This is the time of tension between dying and birth . . . the place of solitude . . . Dust I am, to dust am bending, from the final doom impending help me, Lord, for death is near. –T. S. Eliot, from Ash Wednesday

This is the time of tension between dying and birth . . . the place of solitude . . . Dust I am, to dust am bending, from the final doom impending help me, Lord, for death is near. –T. S. Eliot, from Ash Wednesday

Nebraska, nominated for Best Film this year, is about a family frozen in shoulds and failures, a family for whom most of their hopes have turned to ashes. They risk a journey into the unknown, which is themselves and where they came from, Nebraska. They travel in the past and the present simultaneously, visiting old sorrows and hidden truths. In free fall, they learn a lot, and a lot of what they learn is dismal, some of it scary. But they also learn they can survive, and in each day new life comes into them. Words begin to convey truth. Chances to mean something to each other occur. Love is reaffirmed. In a comedy of errors, everyone breaks rules.

Like pilgrims, they find grace, freedom, and each other, along the way. ‘. . . store up for yourselves treasures in heaven, where neither moth nor rust consumes and where thieves do not break in and steal. For where your treasure is, there your heart will be also’ – Jesus, in Matthew 6: 20-21 In the end, they are rich indeed.

_________________________________________________________

Illustrations:

1. Ash Wednesday. 2006, San Francisco. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.

2. Vanitas. 1659. Gijsbrechts, Cornelius. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.

3. Could Silence Protect Us? 2007. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.