Wading through John’s 6th chapter, dense with repetitious mystical instructions about eating the body and blood of Jesus, is a trip through a sucking bog.

Wading through John’s 6th chapter, dense with repetitious mystical instructions about eating the body and blood of Jesus, is a trip through a sucking bog.

I’ve walked along one of these bogs, not too far from Walden Pond, and listened to its strange, insistent noises, its burps and belches and long wailing siren sounds, and gotten the creeps. John’s 6th chapter can do that to me, too. As, John says, Jesus did to large numbers of those who had been following him. They were creeped out, they had enough, they turned away and went home.

But I wonder, am I reading this right when I hear it the way they did? How could Jesus, who in Mark is so shy to be identified as a savior, and in Luke emphasizes the ordinary and accessible (trees and seeds and birds and bread and wine, as the doorways to holiness) turn into someone who insists on being worshiped as singularly divine and apart from all nature, in the space of a few decades and in the mind of John?

The companion narrative from I Kings, the story of Solomon, gives us an equally difficult fellow to pin down. Solomon was as bad as he was good, as terrible as he was great, as foolish as he was wise. He became legendary for his wisdom and his ability to bring disparate people together. And he also became legendary for his unbridled lust, his 700 wives and 300 concubines.

He built the awesome and cherished Second Temple, revered by Jews today and by hundreds of Sunday school children who have labored devotedly to replicate it as a way of exploring it.

He built the awesome and cherished Second Temple, revered by Jews today and by hundreds of Sunday school children who have labored devotedly to replicate it as a way of exploring it.

Solomon also built temples to a number of other popular gods, and offered animal and human sacrifices in them as part of his politics.

Does Solomon remind us that Jesus, too, has many more dimensions to his character and life than we like to recall, or even know? Does Solomon show us that, for all his greatness, he could never be more than human – and that Jesus, too, wants us to remember his humanity, his flesh, his body and blood, and more than remember it, take him into our flesh, resurrecting him in our bodies, not in creeds we recite or rituals we invent or temples in which we turn him into glass, into gold, into painted effigies we can adore but cannot become?

Is John pointing Jesus’ words towards a gnostic drift that may be present in the community he writes for? Whatever our tradition, most of us manage to separate sacrament from real life, belief from experience, spiritual life from the part of us that makes deals, seeks sex, fumes and fusses about our lives. As Solomon himself did. And as Jesus, according to John, will not allow us to do to him. He will not, if John is right, allow us to make him into a personal comfort, ignoring the allictions of the lost, the least, the despised, the damned. We cannot pick and choose the parts of him we like, and leave the rest, according to John, that would be the real cannibalizing of him. We must, he says, ingest him completely.

Solomon dedicated the Great Temple that held the Ark of the Covenant, saying it was to be a place where people could bring all the dark, howling, disconsolate, desperate, broken, shameful parts of themselves and their lives, and find there, in the presence of God, healing. Here are some of Solomon’s words:

Solomon dedicated the Great Temple that held the Ark of the Covenant, saying it was to be a place where people could bring all the dark, howling, disconsolate, desperate, broken, shameful parts of themselves and their lives, and find there, in the presence of God, healing. Here are some of Solomon’s words:

When your people Israel, having sinned against you, are defeated before an enemy but turn again to you, confess your name, pray and plead with you in this house, then hear in heaven, forgive the sin of your people Israel. When heaven is shut up and there is no rain because they have sinned against you, and then they pray toward this place, confess your name, and turn from their sin, then hear in heaven, and forgive; and grant rain on your land. If there is famine in the land, if there is plague, blight, mildew, locust, or caterpillar; if their enemy besieges them in any of their cities; whatever plague, whatever sickness there is; whatever prayer, whatever plea there is from any individual or from all your people Israel, all knowing the afflictions of their own hearts so that they stretch out their hands toward this house; then hear in heaven your dwelling place, forgive, so that they may fear you all their days.

All of these sins were Solomon’s – these were deep human needs, human aching and groaning, that he knew. Is Jesus, who proclaims himself to be the new Temple of God, insisting that he must come into us, flesh and blood, in order to reach that holy place within us, and also in order to bring to us that holiness within him? Would he, who said he was more than the Temple, consent to be less in our lives than Solomon’s words?

All of these sins were Solomon’s – these were deep human needs, human aching and groaning, that he knew. Is Jesus, who proclaims himself to be the new Temple of God, insisting that he must come into us, flesh and blood, in order to reach that holy place within us, and also in order to bring to us that holiness within him? Would he, who said he was more than the Temple, consent to be less in our lives than Solomon’s words?

At the beginning of his dedicating speech, Solomon declared it was God’s vow to dwell in deep darkness; but also to be the powerful presence of holiness for his people.

Majestic and abundant words, and more than a little creepy. Perhaps my own resistance to Jesus being associated with creepy things is part of my own idolatry. The world, and even my own heart at times, dwells in deep darkness. Body and soul, O Holy One, come into us body and soul.

__________________________________________________________

Illustrations

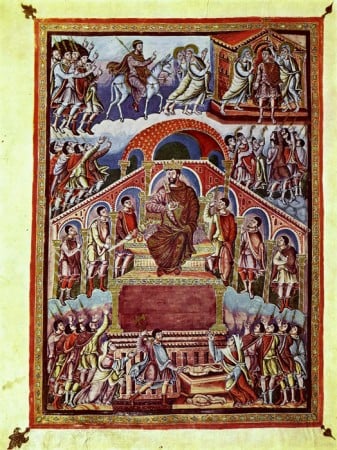

1. Judgment of Solomon. 880 AD. Attributes to Ingobertus. Chiesa di San Paolo, Rome. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.

2. Solomon. Michaelangelo Buonarrotti, 1508-1512. Fresco. Sistine Chapel. Vatican City. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.

3. Solomon Praying to the Holy Spirit. Vrelant, Guillaume. 1481. J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.

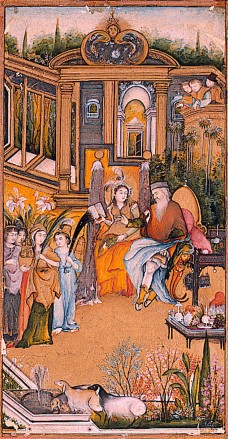

4. Solomon and the Queen of Sheba. 1760 Made in Uttar Pradesh, India. Late Mughal. San Diego Museum of Art. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.