Those whom God hath joined together, let no one put asunder.

Those whom God hath joined together, let no one put asunder.

The words are resonant. I’ve often told brides and grooms their love is blessed by the aura of memories welling up in the hearts of all those gathered to witness their wedding, knowing that for them, as for me, those memories include all the marriages in which we have been embraced.

Yet, in America, statistics show that the median length for a marriage is 11 years, with 90% of all divorces being settled out of court. PolitiFact.com estimated in 2012 that the lifelong probability of a marriage ending in divorce is 40%–50%.

Jesus, according to Mark’s gospel, opined severely against divorce, and warned that those who remarry will be committing adultery. Adultery, sex between a married person and someone other than his/her own spouse, is the only sexual prohibition in the Ten Commandments. The Only.

The Ten Commandments are the highest, most essential body of law in Judaism. Other prohibitions for other sexual behaviors are contained in far less important legal codes in the Old Testament. They exist in lists of prohibited activities, such as eating shellfish, lists that range from moderate to minor in importance, and some of which are provincial – that is, they might apply in Judea but not in Galilee. This makes them much like American laws, which exist on local, county, state, and federal levels. Only the adultery law would be considered the equivalent of a Supreme Court ruling.

The Ten Commandments are the highest, most essential body of law in Judaism. Other prohibitions for other sexual behaviors are contained in far less important legal codes in the Old Testament. They exist in lists of prohibited activities, such as eating shellfish, lists that range from moderate to minor in importance, and some of which are provincial – that is, they might apply in Judea but not in Galilee. This makes them much like American laws, which exist on local, county, state, and federal levels. Only the adultery law would be considered the equivalent of a Supreme Court ruling.

The solemnity of this law is laid out for us in the story of David and Bathsheba, and the lengths to which King David went to cover up his adultery. King David, who had a great number of paramours and cared little about hiding them, who shrugged off the rape of his daughter by her half-brother, had Bathsheba’s husband deliberately exposed to death on the battlefield so that he could then marry her, preferring to endure whispers of assassination rather than rumors of adultery.

Yet in our own times far more shame is accorded in church teachings to other sexual offenders than to adulterers and the divorced. Four-times-married Kim Davis, a county clerk in Kentucky, wrapped in the armor of her religion, has become a national warrior against gay marriage.

Yet in our own times far more shame is accorded in church teachings to other sexual offenders than to adulterers and the divorced. Four-times-married Kim Davis, a county clerk in Kentucky, wrapped in the armor of her religion, has become a national warrior against gay marriage.

The Pope, in his declaration of a year of Mercy, has urged that the divorced be more easily and rapidly restored to full sacramental participation than in the past. The challenge of being Merciful, especially in times of shifting public mores, seems like the right challenge for us to undertake. When divorce was more rare, the stigma associated with it marked the divorcee, and children of the marriage, for life.

For this reason, it was disappointing to me that Saturday’s World Meeting of Families, held in Philadelphia with the Pope in attendance, only included intact heterosexual first marriages with children still living at home. Excluded were blended families which are often remarkably merciful in their construction of home, gay and lesbian families, devoted families in which a widow or widower or a divorcee, a grown child, and one or more grandchildren make a home together. Excluded were neighbors in urban apartment buildings who for forty years have been devoted companions during hospital stays, personal tragedies, and holidays without family members. And most of all, excluded are the families small churches, and groups within larger churches, can become to one another through shared outreach, prayer and support groups. Families do not only exist to tend to small children, and the child in all of us needs to be embraced for our entire lifetime by one family arrangement or another.

For this reason, it was disappointing to me that Saturday’s World Meeting of Families, held in Philadelphia with the Pope in attendance, only included intact heterosexual first marriages with children still living at home. Excluded were blended families which are often remarkably merciful in their construction of home, gay and lesbian families, devoted families in which a widow or widower or a divorcee, a grown child, and one or more grandchildren make a home together. Excluded were neighbors in urban apartment buildings who for forty years have been devoted companions during hospital stays, personal tragedies, and holidays without family members. And most of all, excluded are the families small churches, and groups within larger churches, can become to one another through shared outreach, prayer and support groups. Families do not only exist to tend to small children, and the child in all of us needs to be embraced for our entire lifetime by one family arrangement or another.

Marriage, then, may yet mean something more than we have explored.

Couples do not exist in private worlds but live in human connections that sustain their lives, whatever their particular lives may be about. These connections may shift, but cannot survive being betrayed. These connections may wax and wane, but need a context of sustained goodwill to be able to nurture and to thrive. By these connections, not just couples, but all those within the web of connection, are sustained.

In the first century CE, before birth control and before women had access to the economy independently of men, divorce was a death sentence, sometimes literally from starvation and exposure, and always socially, from shame. In our time, when the economy, our understanding of sexuality, our ability to control fertility, and the law, have changed, when our life expectancy has doubled, and when we no longer live in clans of blood relations, marriage expectations have changed. Today, on NPR’s This American Life, a man made the observation that he had never seen a marriage of forty years’ duration to which he had the reaction, ‘Wow, I want some of that!’

In the first century CE, before birth control and before women had access to the economy independently of men, divorce was a death sentence, sometimes literally from starvation and exposure, and always socially, from shame. In our time, when the economy, our understanding of sexuality, our ability to control fertility, and the law, have changed, when our life expectancy has doubled, and when we no longer live in clans of blood relations, marriage expectations have changed. Today, on NPR’s This American Life, a man made the observation that he had never seen a marriage of forty years’ duration to which he had the reaction, ‘Wow, I want some of that!’

Brigid Schulte, writing in The Washington Post about Gray Divorce in October 2014, observed: By the time my great-grandparents hit retirement age, my great-grandmother was living with one daughter. My great-grandfather with another. The two rarely saw each other, or spoke. They had, my mother explained, an “Irish Divorce:” two people living separate lives and in all ways strangers, disconnected from each other, sharing only an unhappy past and a pair of wedding rings.

Elena Stancanelli, a senior researcher at the Paris School of Economics, was equally shocked when she analyzed divorce data in France and discovered that French couples who’d been married for 35 or 40 years are now as likely to divorce as couples who’ve been married for five years.

Elena Stancanelli, a senior researcher at the Paris School of Economics, was equally shocked when she analyzed divorce data in France and discovered that French couples who’d been married for 35 or 40 years are now as likely to divorce as couples who’ve been married for five years.

The work that lies before us, as Christians, is to explore and expand our understanding of marriage as contextual, and of the nature of what betrays that context, what is adulterous and lastingly harmful in our times. As with all our exploration, it is narrow literalism that trips us up and precludes our understanding and our mercifulness. How we love and how we live, like Christ and the Spirit, rise in endlessly new and inviting ways, asking of us that we believe in God who is new every morning, and who in that newness continues to love. Asking of us that we believe not in the naming of sin, but in our own power to open ourselves to life that is risen, and to be transformed by the renewal of our minds.

____________________________________________________________

Illustrations:

1. Arnolfini Wedding detail, Jan van Eyck, 1434. National Gallery, Great Britain. Vanderbilt Divinity school Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.

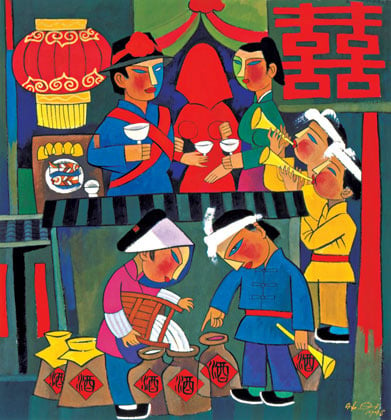

2. Wedding at Cana, He Qi, 2001, Nanjing, China. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.

3. Christ and the Woman Caught in Adultery. Kemmer, Hans. 1534. Besitz des St. Annen Museums, Lubek, Germany. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.

4. The Scarlet Letter. Merle Hugues. Walters Art Musuem, Baltimore, MD. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.

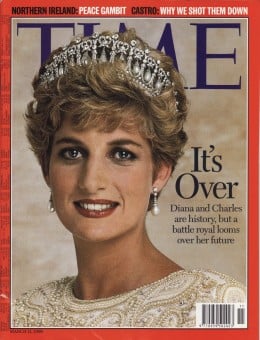

5. Wedding of Prince Charles and Lady Diana Spencer. Enwikipedia.org. Google Images.

6. It’s Over. Time Magazine cover. Google Images.