Things that I have done one hundred and forty times are like that – they are ingrained. They have become habitual.

We all have some of those habits, those ingrained things we do that are so deep they are way beyond conscious decision making, and they are not prompted responses to feelings – though there is a thread of thought in them, and a persistently vague feeling that the absence of doing them is not alright.

Brushing teeth, for instance. On good days and bad, when ill, when exhausted, when so eager for my bed my body no longer wants to stand up, still I floss and brush. It’s a habit I acquired. I dimly remember star charts in the bathroom and my mother holding out the box of gold stars as a lure.

Brushing teeth, for instance. On good days and bad, when ill, when exhausted, when so eager for my bed my body no longer wants to stand up, still I floss and brush. It’s a habit I acquired. I dimly remember star charts in the bathroom and my mother holding out the box of gold stars as a lure.

Good habits are hard to acquire, I’ve found. Take gym routines. How I can make excuses, put off till later, then later still . . . It takes something more than knowing the good in good habits, and more than wanting those habits, to ingrain them.

And bad habits are hard to undo. Ask any smoker, any drinker, any dieter, any worrier. These are not casual desires or fleeting fears. Habits can be defensive and comforting, or preparatory (worst casers are always prepared) or impulsive (saying a reflexive No to new things).

All habits have power. And we come to be known by the habits we develop, our odd, particular, useful, self-destructive patterns.

Jesus advised Peter that forgiveness was to be ingrained in this way, habitually. Shall we forgive seven times? he asked, and Jesus said, No, seventy times seven. Seven times often seems over generous to me. And sometimes once seems too hard. One hundred and forty is beyond counting, really. And it goes beyond the offender. Such a large number, beyond thinking about the offense or the person, goes to the ingrained place where choice is no longer an activity but a reflex, our way of being in this world.

Russell Banks, in The Sweet Hereafter, has school-bus driver Dolores Driscoll confide to us how she waits every day for the same three siblings, who are always late. Time and again she had chided them, but when nothing changed in them she changed herself, turning those extra minutes into a meditative time for sipping coffee and thinking about her life. And so she forgave them, and set herself free.

Russell Banks, in The Sweet Hereafter, has school-bus driver Dolores Driscoll confide to us how she waits every day for the same three siblings, who are always late. Time and again she had chided them, but when nothing changed in them she changed herself, turning those extra minutes into a meditative time for sipping coffee and thinking about her life. And so she forgave them, and set herself free.

For many Catholics, saying the rosary is this kind of self-change, this kind of letting-go of past offenses, this kind of deep-in-the-bone recitation that needs no thought at all, but aids in the necessary draining of the spirit, letting resentment and offenses slowly empty, letting body and soul recover from bruising, regain elasticity, reclaim connection to hope and confidence.

Many years ago, as a young chaplain in Boston City Hospital, nurses asked me for help with a woman who had been badly burned in a fire, had been alcoholic for years, and was dying. The drugs she had been given for pain, together with the alcohol withdrawal, had produced delusions, and she was yelling, screaming, and inconsolable, often talking to people no one else could see. I went into the room and could barely get the woman’s attention, let alone converse. So, because I could think of nothing else to do, I began reciting the Lord’s Prayer, and she turned her face toward me, and after a moment, joined me in it. The Lord’s prayer lived in a deeper place in her than her demons, than her pain, than her fear. I said it again,  and so did she. We kept repeating and repeating that prayer. When I left the room she was still reciting it, and after a while, fell asleep. When she awoke, the process needed to be repeated, but it did calm her, and keep her, for the last two days of her life, from being consumed be her demons. Forgive us our sins . . .

and so did she. We kept repeating and repeating that prayer. When I left the room she was still reciting it, and after a while, fell asleep. When she awoke, the process needed to be repeated, but it did calm her, and keep her, for the last two days of her life, from being consumed be her demons. Forgive us our sins . . .

In the Catholic tradition habit has occupied a premiere position in the religious life. Prayers from the rosary have been assigned as acts of penance for centuries by Catholic priests, and the cycle of habitual prayers marks the hours of every day in the Catholic breviary. Giving up personality and choice in favor of habit has been encouraged. And I both agree and disagree. What love is there without imagination? But forgiveness, at best, is not a response, it is an imbedded part of who we are.

And so much of life falls outside the protection habits offer. So much of life is horrifying, unexpected, and beyond mild words of forgiveness. How could survivors of the German death camps be protected by forgiveness, or even asked to forgive? And yet, for some of them the emphasizing of memories of kindnesses given and received, among prisoners, and from German people whose compassion withstood the rule of evil, became a help in surviving.

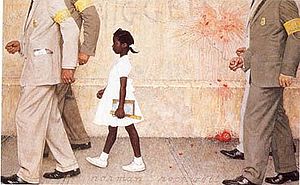

In the 1960s, six year old Ruby Bridges integrated an all-white school by herself, walking there every day with two federal escorts in front of her and two more behind her, while around her an angry crowd of white adults heaped abuses on her little head. Child psychiatrist Robert Coles noticed her lips were moving as she walked, and asked her, in her home, what she was saying. She said she was praying, Father, forgive them for they know not what they do. Her parents hoped, by giving her this prayer, she could shield her mind and heart, and walk unscathed through her daily hell.

In the 1960s, six year old Ruby Bridges integrated an all-white school by herself, walking there every day with two federal escorts in front of her and two more behind her, while around her an angry crowd of white adults heaped abuses on her little head. Child psychiatrist Robert Coles noticed her lips were moving as she walked, and asked her, in her home, what she was saying. She said she was praying, Father, forgive them for they know not what they do. Her parents hoped, by giving her this prayer, she could shield her mind and heart, and walk unscathed through her daily hell.

Nelson Mandela, after 27 years in a South African prison, said, Forgiveness liberates the soul. It removes fear. That’s why it is such a powerful weapon. When asked about his jailers, he responded that forgiving them was a choice to set himself free. He could leave those guards there in the prison instead of remembering them always by nursing resentment. And soon after his release, before his election, when he came to Boston, he danced a little freedom dance for all of us to see.

Forgiving, then, is separate from loving the other, separate from liking, separate from restoring trust in relationship, and certainly separate from forgetting. If we make forgiveness a habit, it becomes rooted far deeper inside us than liking, trusting or forgetting can be. And it becomes about loving God and ourselves, not about loving the offender.

Forgiving, then, is separate from loving the other, separate from liking, separate from restoring trust in relationship, and certainly separate from forgetting. If we make forgiveness a habit, it becomes rooted far deeper inside us than liking, trusting or forgetting can be. And it becomes about loving God and ourselves, not about loving the offender.

Forgiveness, the best power we have, is about survival and freedom. Amen to that power.

__________________________________________________________

Illustrations:

1. Aristotle Poster. Google Images.

2. Toothbrushes. Image from Commons, Wikipedia.org.

3. The Sweet Hereafter book cover. Google Images.

4. Rosary. Google Images.

5. The Problem We All Live With, 1964, by Norman Rockwell. Image from Wikipedia page for the painting.

6. Family Giving Thanks to the Ocean. 2008. Tiruvanimayur, Chennai. MacKay Savage. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.