We are all called to be mothers of God, for God is always waiting to be born.

— Meister Eckart, 1260 – 1327

She enters our Decembers with an angel, gloriously winged, who honors her. The moment is spellbinding: we are entranced by the arrival of this woman, Mary, on the stage of Christmas and in the story of God.

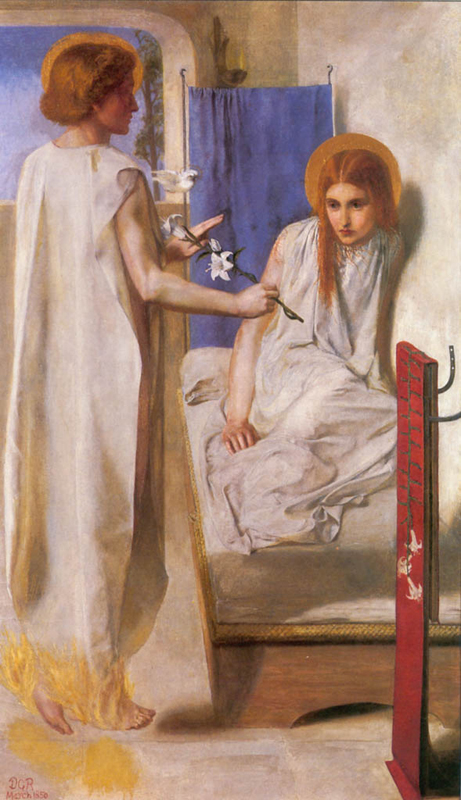

And the angel honors her: Hail Mary, full of grace . . . . Is the angel bowing – kneeling – looking down – while speaking? So very many images say yes, but Luke’s words don’t tell us the posture, only the words the angel says. The poses in the paintings are our awe.

The grace the angel honors is already hers, though she is not yet ‘with child’. It is her grace that has brought the angel, and the invitation. She reflects. She questions: angel-who-are-you, and how can this be? The angel explains: it is your spirit God seeks as Godbearer, and it is God’s spirit that will enter you.

For two thousand years we have chattered, endlessly, about her womb. Yet the angel did not honor her virginity, or her abstinence, or ask for her submission. The honor was for her grace. And by the angel’s persuading her with answers, we know she did not submit: she consented.

The chatter, our chatter, has rendered her a freak of nature. And this has become doctrine. Alone of all her sex, historian Marina Warner calls her. But this is not what the angel honored, not what the angel sought. Nor is it what she consented to become.

Mary, the first woman called as a prophetic servant of God, became the only woman in the prophetic lineage, and one who speaks to Gentiles as well as Jews.

Mary, the first woman called as a prophetic servant of God, became the only woman in the prophetic lineage, and one who speaks to Gentiles as well as Jews.

Her call occurs in the pattern by which Jewish prophets are recognizably called: angels come to them. To Gideon in the winepress, to Isaiah in the temple vision, to Ezekiel in a vision in the sky, to Jonah in dreams in a strange land, angels came asking, will you serve God in this terrible, murderous time?

Each prophet decides, as Mary decides: with questions, some reflection, and a deep understanding of the hope and hardness of what is being asked. They answer with the grace that is in them.

After she says Yes to the angel, Mary sets out on a journey. Alone. And she stays away for months, we are told. Elijah, Isaiah, Ezekiel, Jeremiah, Samuel, Jonah, all set forth on journeys, alone, at the inauguration of their calling as servants. Each bears the word of God to someone who is unlikely to receive it well. Kings, mostly. Mary travels to the home of a prominent temple priest, Zechariah, who has been struck dumb for refusing to believe angelic hope brought to his wife, Mary’s cousin. Upon arriving at Zechariah’s home, Mary delivers her Magnificat, with all the authority and clarity of Elijah speaking to King Ahab.

In the gospels (unlike the paintings), Mary is never shown at home. Most biblical women are shown in domestic scenes, but not Mary: she does not bake cakes as Sarah and the widow of Zarephath do, as Hannah longs to do. Her child is born in a stable, not a house. She then flees to exile in Egypt.

In the gospels (unlike the paintings), Mary is never shown at home. Most biblical women are shown in domestic scenes, but not Mary: she does not bake cakes as Sarah and the widow of Zarephath do, as Hannah longs to do. Her child is born in a stable, not a house. She then flees to exile in Egypt.

After that, she is seen at the Temple when Jesus is twelve, at a wedding in Cana, outside the door of a place where he is speaking, at the foot of the cross and at his grave. Likewise, the prophets are never shown in their homes, places they leave to bear God’s word to places where they are sent.

Mary’s words, like Jeremiah’s, Elijah’s, Isaiah’s, ring with life. There is wildness in them, and immense faith. She says her soul is enlarging God. Not her womb: her soul.

Some compare her song to Hannah’s, who indeed does sing a hymn of praise, but Hannah’s song is full of prayer and longing. Mary’s song is prophetic, bold in its assertion of history-changing life, and her service in that. There is nothing domestic about Mary. And everything domestic about Hannah, who longs for a child so she will be more at home.

Hannah’s child is God’s gift to her; the Child in Mary’s womb is her service to God: deeply physical service which is deeply spiritual. Physical service is true for all major prophets: Isaiah endures hot coals on his tongue. Elijah endures famine, and hides from death threats in the wild for years, and then in the home of the impoverished widow of Zarephath, with whom he shares their only food, flour and oil, for months. Ezekiel suffers exile in Babylon, where he weeps and has visions. Jeremiah, naked except for a loin cloth, runs a marathon for God’s sake, then goes into exile, where he writes the Lamentations. The work of prophecy is physical work: bearing God into a weary and unwelcoming world. Mary bears her child in the most dangerous possible place, a place strewn with the bodies of slaughtered children. In that place she lies down among animals, gives birth, gets up, and flees. And in this she claims that town for God.

Mary sings stunning words: the fruitfulness of the reign of God will be increased through her child.

Mary sings stunning words: the fruitfulness of the reign of God will be increased through her child.

Luke knows that in Greek, and Roman cultures, prevailing cultures in his time, kings receive their sovereignty from goddess-women who become their wives. Their lands, their crops, their wars, as well as their lineage, in sum, their sovereignty, depend upon these women for fruitfulness.

Catholic tradition has long understood Mary as the Queen of Heaven, sovereign of fruitfulness in the reign of God. But Luke, a Greek citizen and a Jew, surely understood that in Judaism the prophets have these powers and this role. Kings need prophetic blessing and anointing in order to reign. Samuel takes his anointing away from Saul, whose kingship withers, and passes it to David. Elijah takes the rain away from the land and curses Ahab’s throne. Jeremiah preserves the claim of God to Israel even as the people are driven out of the land, by solemnly buying land and burying a deed. Mary withdraws the blessing of God from the rich, the proud and the mighty, and gives it to the hungry. She bears a child among the slaughtered, and in this, defines Bethlehem.

Like her European sisters, she has power rooted in nature itself. Her tears, in folkloric tradition, become roses, flowers spring up in her footsteps. She bears her Child among animals, shows him only to shepherds, and outruns an army to protect him from a King whose reign is fruitless. Christmas comes to us through Mary: she is Bethlehem.

All this magic is worked within

the earthy Mary, where the Child

is filled with grace and born with marvelous

capacity, alive and kicking, growing,

laughing, breathing, speaking, waxing wise.

Knitting the eternal into dust,

Mary makes a life that can outlast a lifetime –

mortal, with tired eyes and weary feet,

and immortal, shining, sustaining

even a body broken.

The earth, too, within her deep storehouse,

mothers strength to grow beyond winter,

ponders possibility and providence,

contemplates fruitfulness,

Mary-ing another springtime for this world.

In gathering shadows December cloaks

the cold ground with everlasting light.

We wander among miracles as

the hopes and fears of all the years are met in us.

And it is Christmas, once again.

–from December Light by Nancy Rockwell

______________________________________________________________

Illustrations:

1. Annunciation. Fra Angelico. 1434. Cortona, Italy. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.

2. Annunciation. Fra Angelico. 1417. Perugia, Italy. Image from Wikimedia Commons.

3. Ecce Ancilla Domini! (Behold the Lord’s Servant!) Rosetti, Dante Gabriel. 1849-50. Tate Gallery, London. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.

4. Christ’s Birth. Conrad von Soest. 1403. Bad Wildungen, Germany. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.

5. Adoration of the Christ Child by the Three Wise Men. Albrecht. Durer. 1490-93. Basel, Switzerland. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.

.