The legends of Judas are burned into the story of Holy Week unforgettably. Over the centuries their meaning has changed, along with the imagery associated with the Betrayer of Christ. More than any other figure, Judas is the repository of Christian anti-Semitism, the fire that has flamed out in acts of cruelty for centuries and came to its fullness in the Holocaust.

The legends of Judas are burned into the story of Holy Week unforgettably. Over the centuries their meaning has changed, along with the imagery associated with the Betrayer of Christ. More than any other figure, Judas is the repository of Christian anti-Semitism, the fire that has flamed out in acts of cruelty for centuries and came to its fullness in the Holocaust.

For a thousand years, from c. 900 to the mid 1900s, Holy Week was a dreaded time among Jews, a time when gangs of drunken Christian men could wage terror as an act of piety in Jewish towns in eastern Europe and in Jewish ghettos in western Europe, and there would be no censure of their violence. Christians, who were fasting and attending rituals on many days of this week, were being fed, in art and in sermons, permission to hate Judas and to blame Judas for the death of Christ.

John has the most details of Judas, and is the most condemning, though none of the gospels speak kindly. Matthew calls him ‘traitor’. John, though, portrays Judas as an agent of Satan, diabolos, the implication being that Judas is an instrument in the eternal battle between the forces of light and dark, between God and Satan.

John has the most details of Judas, and is the most condemning, though none of the gospels speak kindly. Matthew calls him ‘traitor’. John, though, portrays Judas as an agent of Satan, diabolos, the implication being that Judas is an instrument in the eternal battle between the forces of light and dark, between God and Satan.

John adds the detail that Judas complained about the cost when Mary poured expensive oil over Jesus’ feet. John attributes this to greed, rather than genuine concern for the poor. Judas is portrayed as a thief who, as the disciples’ treasurer, pilfered from the common purse.

Anglican theologian Graeme Davidson points out that John describes Judas as the sort of person who would have no scruples about selling his master for 30 pieces of silver. Davidson asks, “Why is such an alleged thief still acting as the disciples’ treasurer at the time of the last supper? Surely there would have been some audit on what happened to the common purse over the three years that Jesus was with the disciples? And why is it that none of the other Gospels mention the pilfering? Is this a case of editorial character assassination? And even if Judas were a thief, he would be no different from some of the other company Jesus kept, including the generic tax collectors, or the despised ones, like the disciple Matthew.”

Anglican theologian Graeme Davidson points out that John describes Judas as the sort of person who would have no scruples about selling his master for 30 pieces of silver. Davidson asks, “Why is such an alleged thief still acting as the disciples’ treasurer at the time of the last supper? Surely there would have been some audit on what happened to the common purse over the three years that Jesus was with the disciples? And why is it that none of the other Gospels mention the pilfering? Is this a case of editorial character assassination? And even if Judas were a thief, he would be no different from some of the other company Jesus kept, including the generic tax collectors, or the despised ones, like the disciple Matthew.”

Davidson makes the case that Jesus associated with other terrorists, men who, like Judas, were members of fanatical movements that desired to bring down the hated Roman-imposed kingship of the Herods. Simon the Zealot, also a disciple, was a member of this group, and Galilee was a known hotbed.

At the last supper, according to John, Jesus appears to collude with Judas in the plan to betray him. As Judas leaves to sell his Master to the authorities, Jesus even remarks that what Judas is going to do is so that the ‘Son of Man may be glorified and God glorified in him’. Davidson reasons that without Judas to arrange a ‘private’ arrest, the authorities would have taken Jesus publicly in an act that would have promoted armed rebellion, which would have been confusing for many as to the nature of the kingdom Jesus was proclaiming. Judas is chosen by Jesus to assist him in making this clear.

At the last supper, according to John, Jesus appears to collude with Judas in the plan to betray him. As Judas leaves to sell his Master to the authorities, Jesus even remarks that what Judas is going to do is so that the ‘Son of Man may be glorified and God glorified in him’. Davidson reasons that without Judas to arrange a ‘private’ arrest, the authorities would have taken Jesus publicly in an act that would have promoted armed rebellion, which would have been confusing for many as to the nature of the kingdom Jesus was proclaiming. Judas is chosen by Jesus to assist him in making this clear.

Matthew’s gospel says that, after Jesus’ death, Judas is filled with remorse, returns the money and hangs himself. The authorities then use the money to buy a burial field for the indigent. But the Book of Acts (written by Luke) says that Judas bought a field, then died suddenly and horribly, his bowels gushing out of him, in that field.

For nearly a thousand years Matthew’s account seems to have been the central image of Judas, who is portrayed hanging from a tree, sometimes with devil spirits around him. The first two illlustrations here are from an early Christian tomb, dated 359 AD, and from an ancient French church, circa 1000 AD.

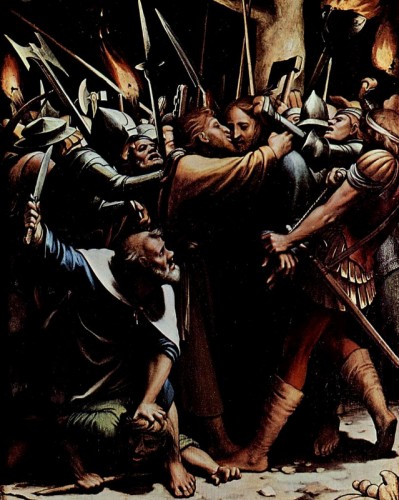

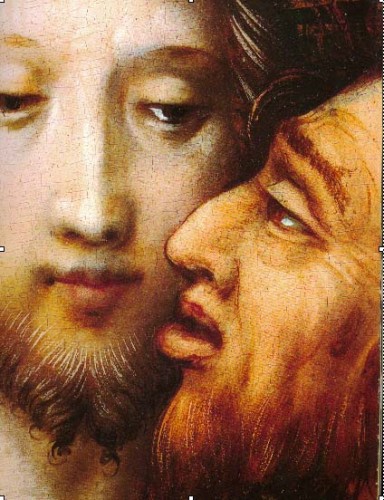

But after this time, and perhaps coinciding with the Crusades when the Vatican became concerned about the inroads of Arabs into Europe and about its religious hegemony in Europe, the desire to de-emphasize the responsibility of Pilate and Caesar helped to shift the blame to Judas, who was now portrayed in the act of kissing betrayal, a questionably intimate, non-political act.

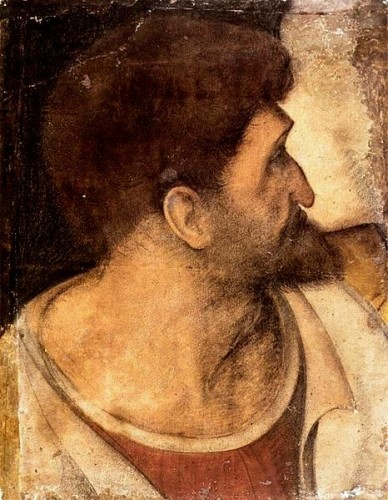

The images of Judas change after this time. He becomes distinctly different, rough, ugly, often darker-skinned, with a hooked nose. Judas is now a Foreigner, an Infidel. He is no longer part of the family of the Beloved. He is no longer an individual disciple, but a representative of a ‘race’ of people.

The images of Judas change after this time. He becomes distinctly different, rough, ugly, often darker-skinned, with a hooked nose. Judas is now a Foreigner, an Infidel. He is no longer part of the family of the Beloved. He is no longer an individual disciple, but a representative of a ‘race’ of people.

For many centuries, these were the only images ordinary people ever saw. Before magazines, cameras, public art other than church art, this iconography was profoundly influential. The identification of Judas with Jews became powerfully evil.

In Holy Week, all of the disciples betray Jesus. The others betray him by promising to be faithful and then falling asleep, or running in fear, or denying him, or hiding. Only Mary Magdalene stays with him while he dies.

Davidson points out that the others learned from their betrayals and spoke of their forgiveness as acts of God’s grace. Judas didn’t live long enough to experience this power. But Judas played a significant role in the story of Jesus, who brought to the world grace to redeem all who have fallen short of the glory of God. Judas deserves a place of honor along with the rest, if we are truly to accept the meaning of the crucifixion of Jesus.

Jorge Luis Borges, the acclaimed Argentinian writer, in 1944 published an essay, Three Versions of Judas, offering three different understandings of what Judas did, all of them essential to Jesus.

Borges’ first argument was that Judas’ kiss was unecessary for identity, Jesus was well known. What was necessary was that the Word made Flesh required a sacrifice of human spirit in parallel descent to the divine sacrifice.

Borges’ first argument was that Judas’ kiss was unecessary for identity, Jesus was well known. What was necessary was that the Word made Flesh required a sacrifice of human spirit in parallel descent to the divine sacrifice.

Judas Iscariot was that chosen man, who abased himself below all men, to balance the sacrifice of God becoming human. Therefore Judas in some way reflects Jesus.

The second Borges argument is that Judas’ betrayal of Jesus was an extravagant asceticism. The ascetic, for the greater glory of God, degrades and mortifies the flesh; Judas did the same with the spirit. He renounced honor, good, peace, the Kingdom of Heaven, as others, less heroically, renounced pleasure. With a terrible lucidity he premeditated his offense. He sought Hell because the felicity of the Lord sufficed him.

Borges’ last argument is based on Isaiah 53, the prophecy of the Messiah as despised and hated among men. This accounts for Judas’ choice to set aside all glory and honor. Judas chose an infamous destiny, to complete the full humanity of Christ, becoming despised and hated of men in order to fulfill the Messianic prophecies for Christ. In this understanding, Jesus and Judas are one, for our sake.

Most of us have learned the theology that we all participate in the death of Christ, but we have also learned to revile Judas as the worst of men.

Betrayal is a painful part of human life. Who has not experienced betrayal, in one way or another? And we are culturally ambivalent about whistle-blowers, who remind us uncomfortably of betrayers.

But what we have not yet owned in two thousand years of Holy Weeks, is the trail of blood and death our judging of Judas has caused. Nor do we own the fear of this Week that lives in those of other faiths who dwell among us, and how easily Judas, in our own time, is transmuted into a Moslem, or anyone who does not kneel down on our holy ground.

For Christ’s sake, may we accept Judas’ kiss as part of our human story, as essential a part of who we are as Peter’s part, or Thomas’, or any of the frightened, confused followers whose love for Jesus has opened to us an Easter of forgiveness and the joy of being part of a world of others who, like us, often behave incomprehensibly, especially when fearful and confusied, but are not a curse upon the world.

________________________________________________

1. Davidson, Graeme, in TheologicalEditions.com, The Case for Judas Iscariot, 2001.

2. Borges, Jorge Luis, in Three Versions of Judas, in Artificios, 1944.

Illustrations

1. Suicide of Jesus, historiated capital from the nave of Saint-Lazare, Autun (France, c. 1120), Musee Lapidaire, Autun. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.

2. Sarcophagus of Junius Bassus, 420AD. St. Peter’s Basilica, Rome. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.

3. Judas. Boltraffio, after Leonardo da Vinci. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.

4. Judas. Hans Holbein. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.

5. The Grey Passion, Hans Holbein the Elder, 1495. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.

6.The Kiss of Judas, Giotto 1304. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.

7. The Betrayal, Fra Angelico. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.