Truly, we live with mysteries too marvelous to be understood.

Truly, we live with mysteries too marvelous to be understood.

How grass can be nourishing in the mouths of lambs.

How rivers and stones are forever in allegiance

with gravity while we ourselves dream of rising.

How two hands touch, and the bonds will never be broken.

—Mary Oliver,

in Mysteries, Yes.

There’s a Russian Easter tale, how it was that the wonder of Easter entered the heart of the world: Mary, Jesus’ mother, stood weeping at the foot of the cross on Good Friday, and Jesus wept for her, too, as he died. And every one of her tears became a beautiful blue and yellow Russian Easter egg as it touched the ground, and everyone of his tears became a deep red egg. At the end of the day Mary picked up all those eggs and put them in her apron, but as she was carrying them away she tripped, and the eggs spilled out of her apron and rolled down the hill of Golgotha, and into the streets of Jerusalem, and they kept on rolling, even to the far corners of the earth, and on Easter the children of the world found them, and they instantly knew about the tears, the love, the suffering, and the life within it all.

Tony Kushner, who wrote the script for the movie Lincoln, also wrote a play called Angels in America, with an old woman quite like the Russian Easter Mary. In the play Rabbi Isidor Chemelwitz speaks about her journey from Russia through the Holocaust, with great reverence. “She was not a person but a whole kind of person,  the ones who crossed the ocean. She carried the old world on her back, in a boat, and she put it down in Flatbush, and she worked that earth into your bones, and you pass it to your children: home. You can never make the crossing that she made, for such Great Voyages in this world do not any more exist. But every day of your lives the miles of that voyage between that place and this one you cross. Every day. You understand me? In you that journey is.”

the ones who crossed the ocean. She carried the old world on her back, in a boat, and she put it down in Flatbush, and she worked that earth into your bones, and you pass it to your children: home. You can never make the crossing that she made, for such Great Voyages in this world do not any more exist. But every day of your lives the miles of that voyage between that place and this one you cross. Every day. You understand me? In you that journey is.”

In the Easter tales, the woman who carries them and works them into the world is Mary Magdalene. Across seas and centuries and cultures she has worked that Easter garden into our bones: her weeping, what the gardener said, what the angels said to her. And her story has become home. Every day we cross the miles between that place and where we are.

She lived in a terrible time. The man she loved more than anyone in the world was suddenly, shockingly, dead. In a murderous time the heart breaks and breaks, and lives by breaking, wrote New England poet Stanley Kunitz, and this is how Mary Magdalene lives. It was into her heartbreak that the angels came, and told her that the death she was sure of cannot be found, and the life she is sure she has lost is not, in fact, over.

In the welter of Easter’s details — Mary saw a gardener, Thomas touched a wound, Peter and James talked to a stranger on the Emmaus road — we come to know about survivors, and in them we see an image of ourselves: their fears and quarrels, the ways in which they disbelieve each other, how they run off in different directions only to discover a truth they cannot escape. Each one has a different version of the story.

Circling, wary, tense, the survivors and Jesus stalk each other down the hours of Easter day, accusing each other in doubt, and disbelieving, even in joy.

Circling, wary, tense, the survivors and Jesus stalk each other down the hours of Easter day, accusing each other in doubt, and disbelieving, even in joy.

It’s hard to say, after all, who took hold of whom in a way that wouldn’t let go. It’s hard to say how, in their terror and their need, Easter came. But that earth, the stories of Easter, came with us, over centuries, through wars, on boats, and it has been worked into our bones. For all our doubts, it’s home.

Home is, of course, as much a mystery as Easter. And mystery is anything you can’t understand: quantum physics, the heart of someone you love, your own doubts and fears, why an old woman from a Russian shtetl, or Mary Magdalene, hang on to us as fiercely as they do. The miles of that voyage we cross every day. In us their journey is.

The essential thing about mystery is not the solution, but choosing your approach: suspicion or love. Suspicion is not without its uses, especially in a murderous time, which is every time, of course.  Still, each one of us could testify from our experience that, on the whole, what is mysterious is best interpreted by love. It was in the fields of Mary’s heart that Jesus rose. Without her love, what story, what life, would there be?

Still, each one of us could testify from our experience that, on the whole, what is mysterious is best interpreted by love. It was in the fields of Mary’s heart that Jesus rose. Without her love, what story, what life, would there be?

And that is the shimmering truth in the emptiness of Easter: the egg of Easter, brimful of tears and torture, blood and death, screams of pain, insults, hate, shattered lives and broken hearts, is now empty: all of it has risen. God’s hand is in this emptiness, showing us that even the most horrible death moves toward life, because God is good, even when we have been evil.

It will be wise and well for us to grasp this mystery tenaciously and not to let it go, to let it take our life into itself. Then death, where you and I are going no matter how we choose to live, will raise us from the fields where we fall, in heart, body, and mind, and carry us lightly, thoughtlessly, as high as eagles soar. (The miles of this voyage you cross every day. You understand me? In you this journey is.)

Well, we will all find out, each of us.

And what would we be, beyond the yardstick

beyond supper and dollars,

if we were not filled with such wondering?

–Mary Oliver, in Evidence

___________________________________________

Illustrations:

1.Noli Me Tangere, Fra Angelico, San Marco, Florence, Italy 1450. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition

2. Mary Magdalene at the Tomb, 1904, Albert von Keller, Munich, Germany

3. Noli Me Tangere, Giotto di Bonodone, 1304-06, Cappella degli Scrovegni, Padua, Italy. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition

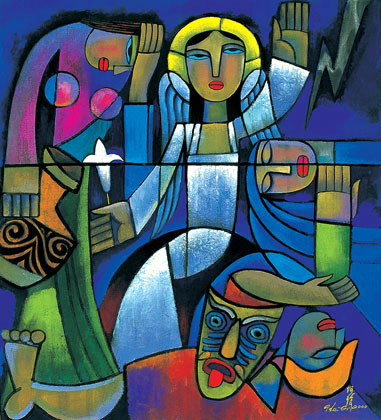

4. Magdalene at Easter, He Qi, Nanqing, China. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition