Like the rocking of the ocean, like the thrumming of peepers in spring evenings, the question Who Is God? is a bass note rhythm in the midst of life, a note that becomes insistent in times when our need to know is great.

Like the rocking of the ocean, like the thrumming of peepers in spring evenings, the question Who Is God? is a bass note rhythm in the midst of life, a note that becomes insistent in times when our need to know is great.

Christian theology answers by calling God the tremendous and fascinating mystery, echoing biblical assertions that God is beyond our knowing. When pressed by Moses for a name, God answers, I am Who I am Becoming (Exodus 3:14).

But the list of actual names given to God in the Bible is huge. Just a few are: Rock, Judge, Father, King, Counselor, Creator, Redeemer, Fortress, Wellspring, Everlasting, Watcher, Presence, Peace, Shepherd.

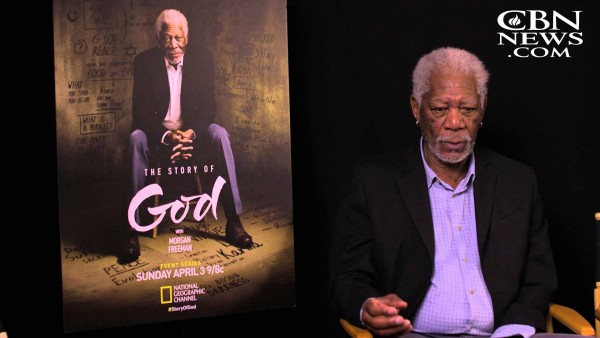

Morgan Freeman begins his journey into the question in India, where there are perhaps three hundred million names for God, and images and stories to go with them.

Some of the images are human, some animal, some combine both, like the tremendously popular Ganesh, a boy with an elephant head. Male and female, with blue, pink, gold and green flesh as well as brown and white, all these deities are manifestations of the one true God Brahma, who is always hidden.

The manifestations, according to Freeman’s guide, help people to feel more intimate with God, help them bring prayers from their hearts that address their immediate needs. Freeman gasps in amazement at temples tucked into market streets, wall shrines on public paths, images in railway stations.

Saints meet similar needs for many Christians, and in Catholic and Orthodox cultures images can be everywhere displayed, but the emotional range is not as broad as in Hinduism, which includes whimsy and gaiety in its divinities, some of whom like to be honored with parties.

Freeman asks, where did the idea of One God begin? And scholarship takes him to Stonehenge, where thousands of years ago, before the pyramids of Egypt and long before Abraham, people without machines raised huge stones in a pattern that honored the sun on its longest and shortest days and in its rising and setting.

One God, they had come to believe, is pure energy, and is the source of life. The ancients, in cold wintry climates, knew they and their animals depended on the sun for food.

The 18th Egyptian Pharoah, Akhenaten (1300 BCE) also believed in one god, Horus, the Sun God. He closed down all other temples, but polytheism returned after his death.

The idea of one god took hold in Judaism, with the story of Abraham, who left a culture of polytheism and went into the wilderness to live with One God. The idea spread, and now half the world practices religions that are centered in Abraham as their ancestor, and in Jerusalem, where a number of sites are tied to his life.

Freeman’s Jewish guide says polytheism offers a god for anything you want, anything you need. The price will differ, from parties to blood sacrifices, but whatever you want is available. I think his distinction is biased, for polytheistic people suffer as many losses and disappointments in their lives as montheists do. But it is true that the one God of Judaism survives sweeping changes in the world, and wants us to survive obstacles and perils in our lives. We will not always get what we want. I think all people know that.

Jerusalem holds holy sites: the Dome of the Rock, where Abraham almost killed Isaac and learned, from God, there was never again to be sacrificing of children. The Mount of Olives and Gethsemane, the Western Wall, each a testimony to love and sacrifice, to evil and survival. These are shrines, but they are not representations of God, whose offers us law, order, and power, also holy teachers, but no image.

So how do we connect to a god without a body? Freeman explores this question in Islam, the least imagistic faith that follows Abraham’s way.

In Islam, the Muezzin’s call to prayer, offered in public five times a day, is considered a manifestation of God. It arises from a vision a friend of Mohammed’s had while he slept, and has been in practice ever since. Islam centers in prayer, which is where the faithful meet God. Islam sees God in all things beautiful, but knows God is always more, and is best known in prayer.

Freeman moves to a Navajo reservation, where a young girl is undergoing a rite of becoming a woman, through a ceremony that joins Changing Woman, the god who infuses the entire landscape, to her, infusing her with holiness and fertility. And then Freeman is off to Chicago, where a neuroscientist studies the brains of people at prayer, and finds physical manifestations in them, while they pray.

In us. All monotheistic religions connect to God internally. Freeman turns to Joel Osteen, a Christian whose TV audience numbers in the hundreds of millions, and who offers personal, approachable, hopeful connections to God, in music, words, and prayer.

There’s a bit of God in all of us, Freeman opines at the end. And my heart turns to an ancient Celtic prayer from the Scottish highlands:

Thou art the joy of all joyous things,

Thou art the light of the beam of the sun,

Thou art the first door of hospitality,

Thou art the surpassing star of guidance,

Thou art the step of the deer on the hill,

Thou art the grace of the swan swimming,

Thou art the loveliness of all lovely desires.

__________________________________________________________________________________________

Image: Morgan Freeman, youtube image with poster for The Story of God.

Prayer: from The Carmina Gadelica, edited by Alexander Carmichael.