The apple doesn’t fall far from the tree is a familiar adage, more often than not used ironically, but sometimes admiringly, about qualities of character, personality, or fate, as they emerge in generations of adults in a family.

The apple doesn’t fall far from the tree is a familiar adage, more often than not used ironically, but sometimes admiringly, about qualities of character, personality, or fate, as they emerge in generations of adults in a family.

The nature of the argument in John’s long tale, about the encounter between Jesus and the community of the man born blind, is about the continuity of seed and sin. Whose fault is it that he is blind? Did his parents sin? Did he sin before he was born? Or is the devil at work in some other form here?

Or, is it the truth, as Jesus says it is, that tragic events exist in our world as opportunities for the work of God – which is love – to be shown?

The frame of John’s story is a long argument about sin and goodness, about misfortune and blessing. Jesus and a his followers happen upon the man born blind begging along the roadside, and the disciples ask Whose sin is this?. Jesus says no one’s, and this is an opportunity for God’s work. And he makes a plaster of dirt with his own spit, and applies it to those blind eyes with his fingers, then tells the man to go and wash, which he does, and comes back seeing. It was the Sabbath.

How did this happen? A more intense argument begins. The man, now seeing, tells the crowd what Jesus did. No one believes him. They take him to the local leaders who rule over matters of virtue and sin , to whom he gives the same answer, and again is not believed.

How did this happen? A more intense argument begins. The man, now seeing, tells the crowd what Jesus did. No one believes him. They take him to the local leaders who rule over matters of virtue and sin , to whom he gives the same answer, and again is not believed.

Is this the same man, the leaders ask. The parents are sent for, and they say this is our son and we don’t know how it happened, ask him.

This is the Sabbath. Therefore Jesus was a public sinner to do this work. The leaders are indignant and ask the young man what kind of person Jesus is. Emboldened, annoyed, frustrated at their refusal of his healing and his joy – all this and more, perhaps, brings out of the young man a longer, slightly surly response: he is a prophet. Why do you keep asking? Do you want to be his disciples? They revile him for his insolence. He protests, in order for Jesus to do this work, God must be with him. And he is further reviled, for they say, You were born in sin, and do you dare to teach us? And, staying in questions born of suspicion, unwilling to consider wonder, they cast him out.

This whole convoluted argument, and the unwillingness to accept people once considered unacceptable, is embedded in our cultural conversation about sexuality, intimacy, marriage, race, and family life. The blind no longer beg in the streets, but I cannot think of any who have advanced far in public leadership. Some churches will not ordain the blind.

This whole convoluted argument, and the unwillingness to accept people once considered unacceptable, is embedded in our cultural conversation about sexuality, intimacy, marriage, race, and family life. The blind no longer beg in the streets, but I cannot think of any who have advanced far in public leadership. Some churches will not ordain the blind.

Gay, lesbian, transgender and bisexual people live in a strobe-lit milieu of acceptance and endangerment. The Church is a mined field of condemnation and acceptance, parish by parish and denomination by denomination. Mental illness has become the public whipping boy for serial killings. And whose fault is it? is the leading question in the public mind at every tragic event. The first black President has been subjected to endless suspicion, beginning with his birth certificate, and for some, these suspicions never go away.

The emboldened responses of those no longer willing to be rejected can infuriate those not willing to consider acceptance. Congregations, placing a high value on niceness, and with an eye on pledges, can be reluctant to engage questions of inclusion and difference.

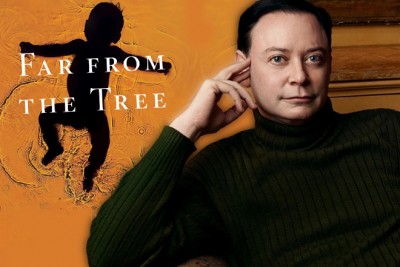

Andrew Solomon, in his 2012 book Far From the Tree, explores the startling proposition that being exceptional is at the core of the human condition—that difference is what unites us. He writes about families coping with deafness, dwarfism, Down syndrome, autism, schizophrenia, or multiple severe disabilities; with children who are prodigies, who are conceived in rape, who become criminals, who are transgender. While each of these characteristics is potentially isolating, the experience of difference within families is universal, and Solomon documents triumphs of love over prejudice. All parenting, he writes, turns on a crucial question: to what extent should parents accept their children for who they are, and to what extent they should help them become their best selves. Drawing on ten years of research and interviews with more than three hundred families, Solomon mines the eloquence of ordinary people facing extreme challenges.

Andrew Solomon, in his 2012 book Far From the Tree, explores the startling proposition that being exceptional is at the core of the human condition—that difference is what unites us. He writes about families coping with deafness, dwarfism, Down syndrome, autism, schizophrenia, or multiple severe disabilities; with children who are prodigies, who are conceived in rape, who become criminals, who are transgender. While each of these characteristics is potentially isolating, the experience of difference within families is universal, and Solomon documents triumphs of love over prejudice. All parenting, he writes, turns on a crucial question: to what extent should parents accept their children for who they are, and to what extent they should help them become their best selves. Drawing on ten years of research and interviews with more than three hundred families, Solomon mines the eloquence of ordinary people facing extreme challenges.

Jesus, in John’s gospel, also mines these situations, as public teaching opportunities and, in his own words, as opportunities for loving action. He proclaims the diversity that unites, to Nicodemus, the woman at the well, the man born blind, Lazarus in his grave. In all these stories Jesus confronts deep prejudices with loving action. Jesus does not try to walk a middle ground, or to move slowly enough to bring the reluctant along, nor does he consent to argue the fine points of the law about Sabbath work or bodily virtue. He confronts. It is time to change the public outlook, he declares – to use his very words as written in John: “I came into this world for judgment so that those who do not see may see, and those who do see may become blind.”

Jesus, in John’s gospel, also mines these situations, as public teaching opportunities and, in his own words, as opportunities for loving action. He proclaims the diversity that unites, to Nicodemus, the woman at the well, the man born blind, Lazarus in his grave. In all these stories Jesus confronts deep prejudices with loving action. Jesus does not try to walk a middle ground, or to move slowly enough to bring the reluctant along, nor does he consent to argue the fine points of the law about Sabbath work or bodily virtue. He confronts. It is time to change the public outlook, he declares – to use his very words as written in John: “I came into this world for judgment so that those who do not see may see, and those who do see may become blind.”

The death of Fred Phelps, the firebrand who twisted and tortured Scripture in his rage to punish sexual sins, brings to mind another adage, that the Devil can quote Scripture, as well as some sadness, that Fred was never able to change. John’s story of the man born blind holds up a two thousand year old wonder, and the blindness of those who, like Fred, could not see it.

Jesus, in these stories, calls to us: Now is the time. And we are the people. Love is the way. Are you ready to be apples of my tree?

________________________________________________________

Illustrations:

1. Christ Healing the Blind Man. Duccio, di Buoninsegna, 1319, National Gallery, London. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.

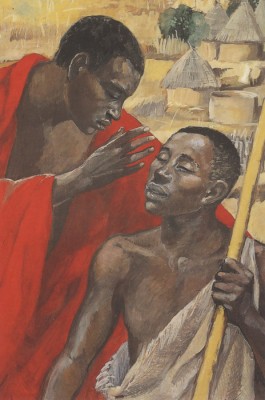

2. Healing the Blind Man. Jesus MAFA, 1973. Paintings from Photos of Reenactments, Cameroon. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.

3. Icon, Healing the Blind Man. Google Images, from a blogspot blog called Stupidity and Humility.

4. Andrew Solomon and Far From the Tree. Book cover image.

5. Christ Healing the Blind. Colombel, Nicolas, 1682, St. Louis Art Museum. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.