Jesus intervenes in death three times, according to the memories of his friends. All four gospels tell the story of the restoration of Rabbi Jairus’ daughter. Only John tells the tale of the raising of Lazarus from his grave. And only Luke tells the story assigned for this week, of Jesus raising the son of a widow from the pall on which he is being carried to his grave.

Jesus intervenes in death three times, according to the memories of his friends. All four gospels tell the story of the restoration of Rabbi Jairus’ daughter. Only John tells the tale of the raising of Lazarus from his grave. And only Luke tells the story assigned for this week, of Jesus raising the son of a widow from the pall on which he is being carried to his grave.

In each tale Jesus jars the sensibilities of his witnesses, who are gathered for the rites, rituals and the responses people offer in times of death: solace; company on the journey to the grave; and mourning. The courtyard of Jairus’ home is full of people offering tears and solace for the little girl’s dying – Jesus walks through them all and raises her to life. Mary and Martha, Jesus’ dear friends, are mourning for their brother – Mary beseechingly sobs, ‘If only you had come sooner, he would not have died!’. In horror, Martha, seeing that Jesus means to raise Lazarus, protests, ‘Lord, it is four days, and he stinketh. (KJV)’

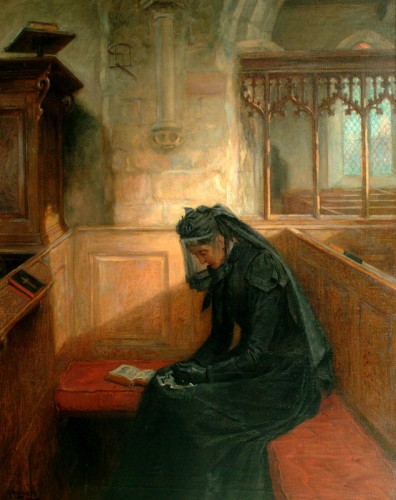

In Luke’s tale, Jesus interrupts a funeral procession, which in any culture is a violation and in his culture was an act of uncleanliness, a sacrilege in the midst of a ritual. Each raising challenges those who are prepared for, and in many ways have accepted, the death.

The actions of Jesus come in response to the broken hearts of mourners. He does not raise the dea d in response to the dead, or as a protest to death.

d in response to the dead, or as a protest to death.

Jairus’ devotion and self-humbling, Mary’s weeping, and the widow’s desperation move Jesus to his interventions. So if it can be said that these tales hold out promise, the promise is for the grieving. But it is also true that many died and he only raised these three. There were indeed several whom he pulled back from the brink of death, and others whom he lifted from slow and lingering suffering. But only these three were brought back from the finality into which they had descended. Commonly, Christians have assumed that our role in the story is to healed from death. But it would be unseemly and unfaithful for us to assume that we are all jockeying to be one of the few. And even worse to assume that Jesus picked favorites among the mourners.

What, then, is the meaning of the few, among the many? Is it perhaps the fulfillment of the promise of Isaiah, the giving of a garland instead of ashes, of the oil of gladness to replace mourning?

Or does it show us how much our grief affects the heart of Jesus? Is he gathering strength from these events which he will need to raise himself at Easter? Is resurrection a response to the tears of those who loved him? Are the tears of our hearts the thing from which our God draws life, unlike all the other gods of this world, whose lives are fueled by warfare or offerings of riches, by subjugation of human will or adoration of divine power?

The 70s film ET showed an extraterrestrial who survived on the strength of his heart, which glowed with fire when he thought of his home. Eventually he was raised to his spaceship on the beam of his heart’s fire. Death, for ET, was separation from those he loved.

The current film of Henry James’ century-old novella, What Maisie Knew, shows a child, caught in a bitter divorce, living through the death of her family, which occurs in a strange procession of events, comings and goings in which her home life falls apart. She is carried around and buffeted by bickering parents and the strange winds of chance. Maisie follows her heart to those who will protect and nurture her.

The current film of Henry James’ century-old novella, What Maisie Knew, shows a child, caught in a bitter divorce, living through the death of her family, which occurs in a strange procession of events, comings and goings in which her home life falls apart. She is carried around and buffeted by bickering parents and the strange winds of chance. Maisie follows her heart to those who will protect and nurture her.

A third film, Hannah Arendt, tells the story of a Holocaust death camp survivor teaching in New York City in the 1950s, who covers the trial of Adolf Eichmann, Nazi leader and overseer of the camps. She worked at the meaning of all these deaths, and of Eichmann as a man, and she worked at discerning the nature of evil. Eichmann was accused of being an unfeeling monster of a man. Her report for The New Yorker Magazine, also published as a book, raised howls of controversy, because she claimed Eichmann was an ordinary man with ordinary feelings, who did not engage in thinking about the morality of his actions. Arendt came to understand the crimes of Eichmann as crimes against humanity rather than crimes against Jews, for, she said, the essential point is that Jews are human beings, and an assault on any one is an assault on everyone.

Arendt also made the point that evil is ordinary and banal, not extraordinary or radical. Only good, she said, can be both ordinary and radical. It is the ordinariness of evil, the way in which it crops up in unthinking decisions, that is the root we need to be looking for.

Her opponents wanted to have an emotional response to evil, and wanted to see WW2 as Great Evil overcome by Holy Good. And they wanted to judge Eichmann for not feeling their feelings. Arendt would not allow them, or any of us, to be spectators, judging evil or good by its proportion, but insisted on their and our involvement in discerning the ordinary actions of every day, and their accumulation of consequences.

Her opponents wanted to have an emotional response to evil, and wanted to see WW2 as Great Evil overcome by Holy Good. And they wanted to judge Eichmann for not feeling their feelings. Arendt would not allow them, or any of us, to be spectators, judging evil or good by its proportion, but insisted on their and our involvement in discerning the ordinary actions of every day, and their accumulation of consequences.

Jesus pushes us to see that death is not a Spectacular Evil. It is ordinary and banal. Indeed, the three whom he raises will have to die – again. And the next time, they will die for good. But in the meantime, the connection in which death has been reversed is the connection of hearts. Love makes it possible for ordinary good to become radical, and extraordinary. He will make this point again, at the Last Supper, and again, on Easter Day.

If we are to know the wonder of life in the midst of death, then we must be aware of this wonder in our transactions and our decisions. Our hearts must move us to become more than spectators watching death and life, processing to the graveyards ritualistically or gathering at the doorway to wail for what we have already accepted, seeing the dead as Not Us.

If we are moved to becoming people who are diminished by the suffering of others, we may begin to understand what it means to be human, as the children around ET, and the nanny of Maisie were moved and did learn. And we may also learn what it means to do good.

Then we may understand the difference between good and evil at last, and we may understand which of our ordinary decisions increase the power of evil, and which restore life in the valley of the shadow of death.

____________________________________________

Illustrations:

1. The Widow, by Ralph Hedley, 1848 – 1913

Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.

2. Ash Wednesday. 2006 photo. San Francisco, CA> Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.

3. What Maisie Knew film poster, Google Images

4. Hannah Arendt film poster. En Wikipedia.org