For some time now, I have been writing the story of how I went from being a devout Evangelical Christian to being an atheist.

I always mention, even the shortest descriptions of my deconversion that reading The Portable Nietzsche was instrumental in my deconversion. I read it May 17-27, 1999 and I wrestled with Nietzsche through October 30, 1999 when I finally deconverted. In an interview with Bret Alan from the blog Anything But Theist I detailed what Nietzsche’s influence on me was like:

DAN: I got into Nietzsche when a close friend of mine in college went through a severe crisis of faith based on reading Nietzsche. We were both devout evangelical Christians at a religiously and politically hard right wing college and at the end of freshman year Nietzsche got under his skin when we both took Ethics together. Nietzsche loomed over our discussions for the next couple years as my friend’s doubts became stronger and stronger and as he flirted with full out philosophical skepticism and an almost suicidal nihilism.

Eventually it was an existential urgency that I fully encounter Nietzsche for myself so I read the entire The Portable Nietzsche

in 10 days and it knocked the spiritual wind out of me. After that I struggled for 5 months before abandoning the faith.

BRET: I’ve noticed there’s two sort of paths to atheism, one where the faith pushes you out, and another where atheism draws you in. For example, I became an atheist by reading the Bible, whereas you became an atheist from reading the thoughts of someone criticizing religion. Do you think there’s something to that?

DAN: Sure. There are a few more ways to break it up. But I loved being a Christian and never thought of things like hypocrisies or the strangeness and immorality of the Bible being a threat to my faith. For me it was just a long journey of trying to defend against external philosophical attacks, from when I was 14-21.

Where Nietzsche really got under my skin was where he shifted the ground to the ethical. Believing became a moral matter and Nietzsche’s power was not in making philosophical arguments against the faith. I could develop those on my own and already had through years of studying philosophy. But what he did was present this defiantly alternative perspective on the world. It was really like visiting a whole other universe reading Thus Spoke Zarathustra

and it profoundly messed with my mind in ways that could not be articulated.

It was like I had spent all these years building these elaborate apologetic routines and then encountered this literary masterwork that just ignored all that and moved on completely from my clever little excuses and assailed the very ethos of my beliefs and painted this picture of a whole different world with a whole different, rival, coherent ethos.

It’s very hard to explain how it worked, but it was like basically like being beaten by someone so far out of your league you have no idea what hit you. And so I spent the next 10 years trying to figure out what exactly had happened.

BRET: What rival ethos does Nietzsche present?

DAN: Well, I’m thinking specifically of the Nietzsche one finds in Thus Spoke Zarathustra, so I’ll say it’s “Zarathustra’s” ethos. Not the historical Zarathustra, of course, but Nietzsche’s.

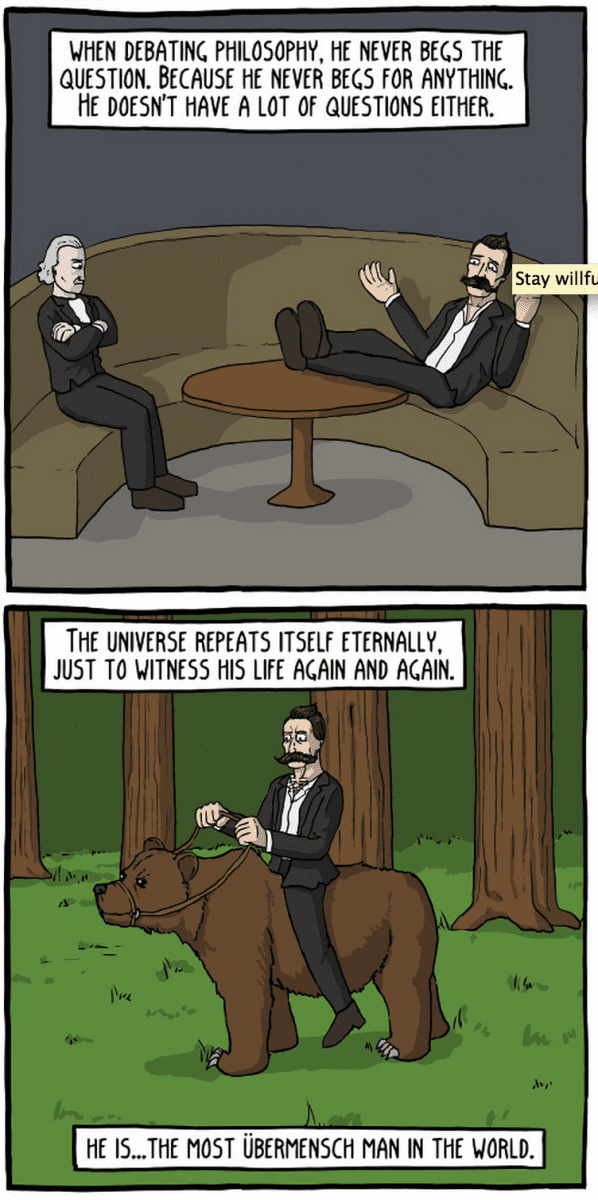

Zarathustra has this sort of high minded seer demeanor about him. He is this character who just has contempt for all pettiness, for all backwardness, for all weakness, for all hatred of the body and the world. And this desire to affirm nature and the body and to look at the future as a place of open-ended transformation of values. There is this overwhelming feeling like we can do so much better as human beings if only we took the dare to radically question our values and overcome everything weak in our humanity. Zarathustra is all about air that is both rarefied and fresh.

He’s incredibly inspiring. It’s by far Nietzsche’s most visionary and positive and inspiring work. But at first it was devastatingly challenging. It was a world that I didn’t fit into, and which had utter contempt for me, and which landed so many blows to my faith indirectly. Again, it’s really hard to describe the effect. It was emotional and “spiritual”.

BRET: Do you find that odd, that something spiritual led you to atheism?

DAN: In a way it makes perfect sense because a religion gives someone a Gestalt that integrates one’s “spiritual” feelings with one’s metaphysics and values and identity and community. It’s a whole way of thinking, feeling, and practicing. When someone says it’s false, well it sure does not feel false. It seems to be ordering your life wonderfully–if you’re one of those people it works for.

And so it makes sense that it was a powerful alternative ordering of things that hooked my emotions and challenged my identity directly. It took superior intellectual content which also had a mesmerizing charismatic appeal that invited my religious mind into a full perspective that it could try on and feel overwhelmed by and eventually have a Gestalt shift within—and then have a wholesale change of feelings right along with it. So, I became a zealous Nietzschean. Until I could finally separate myself from him and move on. But that took a while.

BRET: So you aren’t one of the mechanical atheists who pretend they are logic machines with no emotions?

DAN: Not at all. I am flabbergasted when Christians who know me disingenuously try to pull that card on me. They know I wear my heart on my sleeve and they can see that I’m brimming with passion for philosophy and for atheism. They just take my words insisting that we be very rational and apportion our beliefs to evidence and say that must be a cold way of life. But they must see in front of them an atheist who is decidedly living hotly.

Yesterday an old friend I knew only in college (who is also now a philosophy professor) read both that post and another one in which I said that when I first became an atheist I committed to only believing things I could not refute. I had misspoken and he caught me exactly when he said:

Maybe what you meant was “I was comfortable not adopting any positive philosophical propositions until I simply couldn’t *resist* them”. That’s certainly a stronger standard. Maybe you found yourself psychologically incapable of resisting the belief that there is no God.

Yes, that’s right. I was committing to only holding positions that I could not resist, not that I could not refute. In a post from the summer about my deconversion I had put the point more accurately when I said that at that time I committed that I would “not believe anything until I could not but believe in it.” I was writing sloppily yesterday and so I am grateful to Jason for correcting that.

Then Jason wanted to know if the reason I felt compelled to believe there was no God was psychological, faith-based, and/or based on evidence and arguments. Alluding, I believe, to the post above in which I talked about the effect of Nietzsche’s ethos in overwhelming my faith away, he casts doubts that I really became an atheist out of my commitment to evidence and arguments:

If so, was it evidence and arguments that made this impossible? Trying to find the answer to this, I looked around at some of your other posts and it looks like the answer is ‘no’. What you say about Nietzsche is that he presented an alternative, coherent ethos that made you question that of Christianity. You report having found yourself attracted to it on a passional level, at least if I understand you correctly. If that’s right, then it looks like you went to atheism instead of agnosticism not because the evidence and arguments for the non-existence of God rationally demanded belief instead of suspension of belief, but rather because you were passionally attracted to an atheistic ethos. I don’t want to say that that’s irrational, but it certainly looks like you replaced one faith with another. Maybe you wouldn’t be bothered by that claim, although I seem to recall you lumping faith with irrationality. (I suppose you might be using ‘faith’ as a technical term, and I just haven’t come across the definition yet.)

Let me first say that the justification for my current reasons for disbelief do not depend on my initial reasons for disbelief having themselves been justifiable (or unimprovable).

That said, let me clarify why how my initial reasons for disbelief were based on arguments and evidence even as Nietzsche’s importantly emotional and ethical appeals were decisive to my deconversion and how deconverting in the way I did was not tantamount to adopting a faith.

I define faith in a technical sense. Faith is willfully committing (whether explicitly or implicitly) to relationships of trust and/or belief (a) beyond perceived rational warrant, (b) against perceived predominance of counter evidence of untrustworthiness, and/or (c) against all possible future counter-evidence that may undermine currently perceived evidence of trustworthiness.

I did not have faith in Nietzsche. Over the 3 years leading up to my reading the Portable Nietzsche I had become convinced more and more that unless one took recourse to faith one would have to have minimal metaphysical beliefs. I was profoundly influenced by Hume in this regard. I had also studied church history and had my naive assumptions about the rationally likely truth of the Scriptures cleared away–even though I was studying in as conservative and believing-friendly a context as I could have been.

Before ever seriously studying Nietzsche, I was opting to believe while explicitly knowing that it was less than entirely rational to do so. I was spending a year bashing reason. I was a misologist, a Christian relativist, and a fideist desperately trying to hold my faith together. The only way I could do it was with an explicit and knowing Kierkegaardian leap of faith that I took as a last ditch effort. I was already convinced that on rational grounds Christianity collapsed and looked untrue. The night where I confronted most strongly the doubts that had grown in me extraordinarily quickly upon starting to formally study philosophy was described in my post December 8, 1997.

Still wanting to feel justified, I tried to argue on presuppositionalist grounds that if only one adopted by faith the absurdity of Christianity’s basic contradictions everything else could be made to have more rational and coherent sense! And there would be a better ethics too! My thought was a muddle. I was keenly aware of how irrational the faith was but tried to justify that by exaggerating the problem of incommensurability to essentially be a relativist about knowledge, denigrating all “worldviews” equally, so that my Christianity would not be any worse by comparison but might at least be better for its streaks of absolutism from within the system. I was clinging, when one looks back, because of deep identity commitments that motivated my psychology and reasoning.

So what did Nietzsche do? Nietzsche followed out my skeptical tendencies in ways that were rational to me. Then he countered my presuppositionalist’s prejudice that my Christian take on the world was the clearly superior one for internal coherence by bringing me into a powerful and evocative and far reaching counter-picture of the world which struck me as both truer and more emotionally resonant.

No, Nietzsche does not offer a bunch of arguments against the existence of God. He didn’t need to. I already knew damn well the reasons not to believe. I knew how irrational my faith was. Yet I was clinging. Nietzsche revealed to me psychologically that it was a lie that Christianity was the only way to see or to feel the world that I was capable of. He made it so that psychologically I could start to transition emotionally out of that identity that overwhelmed everything else for me and kept me from being true to my reason.

He put together an alternative Gestalt that I could see the world with that made more sense of it than the Christian account. And his Gestalt did not involve having to cling desperately to a moral dispensation to believe as I desired (“faith”) in the teeth of evidence as I had been doing. In fact what Nietzsche impressed upon me was that as a primary ethical and intellectual commitment I should be true to my reason, even at the expense of my faith and my very identity–and even at the expense of my confidence in having robust rational truth. I felt pushed to say that even if all reason could tell me was that it itself could not be fully trusted, then I would simply have to be a radical skeptic. The solution to radical skepticism was not choosing by faith to believe in whatever unjustified beliefs we wished, as I had been doing. The only option for my intellectual conscience was to provisionally be a fearless nihilist with a patient project of investigating every proposition with rigorous skepticism before assenting to it.

I needed Nietzsche’s psychological pull because my reason was fettered with the traps of identity that had me constantly deliberately attacking it. Nietzsche gave the emotional force to stop feeling like the only good in the world could ever be Christian, and like the only way I could see the world could ever be as a Christian. Nietzsche deprogrammed me. He didn’t give me a new “faith”. He convinced me that it was okay to doubt, to not know, and to think beyond the Christian box–as I had been intellectually prepared to do for well over a year already but had not been emotionally able to seriously contemplate yet.

Then when I left the faith, I trusted Nietzsche more than anyone else for a time because psychologically I responded to him being the one who had liberated my mind. That was why I was so zealous about him. I trusted gratefully his willingness to ask any question, no matter how dangerous or uncomfortable. He embodied to me the most fearless commitment to intellectual conscience–not faith. I didn’t believe he was infallible. I would not believe things simply on his word. I would not believe him when he was contravened by evidence. I would not commit to believing in him “regardless of what new evidence came up”, etc. I did not commit to believing in Nietzsche volitionally as a faith-believer commits to believing in the propositions of their faith.

What I did do was try on his perspective as best I could. I adopted his principles of skeptical rigor since I thought them the only rational option. And I agreed with many of his skeptical conclusions about universals, the self, free will, etc. In each case I just found his reasons compelling–it was not a matter of willful faith. Soon as someone could disabuse me of some Nietzschean position or another I would let it go. And on many issues I never agreed with him. But I would try on many ideas I was not necessarily persuaded of in order that I might think within his system and understand it more intricately, and eventually assess its truth more accurately as a result. This enabled me for my dissertation to write as plausible an account of his philosophy’s internal coherence and constructive possibilities as I could–and then to feel completely comfortable walking away from every part of it that did not ultimately persuade me or which I had come to be dissuaded of by that time. Which was quite a bit!

Within two and a half years of my deconversion even, (May 2002) Thomas Aquinas convinced me of the soundness of teleological categories–even though I found the theistic framework he had them in wholly unjustified and unnecessary. I didn’t panic when my previous anti-teleological beliefs were shaken. I didn’t reject the arguments of Aquinas because they were antithetical to some “faith” commitment to Nietzsche and against teleology. When I finally understood the logic of the concept, I just became a teleologist. Teleology gave no reason at all to believe in a God, and it needs to be wholly updated for the 21st Century to be rationally plausible, but I think it can be so updated and that it can support a godless metaethics. I would even eventually come to think that some of Nietzsche’s implicit teleological thinking was more important to making coherent sense of his overall project than his outward hostility to teleology, and so that played heavily into how I argued he would be most fruitfully systematized.

Over the course of years of study and debate, my skepticism about epistemology and about ethics and about metaphysics each was overcome, one by one, only after I finally came across arguments that really compelled belief from me against the most vigorous skepticism I could muster. I did not embrace my positive views about epistemology, ethics, or metaphysics out of a willful commitment to them regardless of evidence. I hung in there for years making minimalistic and merely pragmatic metaphysical, ethical, and epistemological statements and arguments until I finally found arguments I could not but believe, which supported robuster concepts of each of them.

That was the antithesis of what religious faith–volitional commitment to believe in wholly improbable things out of commitment to one’s irrational religious identity and community–involves.

Your Thoughts?

My friend leveled more critiques of my deconversion narrative here and I answered them at greater length here.

I also discuss Nietzsche’s impact on my deconversion and its aftermath some more in this post about my first year or so thinking as a non-Christian and in this one about what potential constructive roles willful blasphemy and mockery of religion can play in rationally deconverting someone.

Read posts in my ongoing “deconversion series” in order to learn more about my experience as a Christian, how I deconverted, what it was like for me when I deconverted, and where my life and my thoughts went after I deconverted.

Before I Deconverted:

Before I Deconverted: My Christian Childhood

Before I Deconverted: Ministers As Powerful Role Models

Before I Deconverted: I Was A Teenage Christian Contrarian

Before I Deconverted, I Already Believed in Equality Between the Sexes

Before I Deconverted: I Dabbled with Calvinism in College (Everyone Was Doing It)

How Evangelicals Can Be Very Hurtful Without Being Very Hateful

Before I Deconverted: My Grandfather’s Contempt

How I Deconverted:

How I Deconverted, It Started With Humean Skepticism

How I Deconverted, I Became A Christian Relativist

How I Deconverted: December 8, 1997

How I Deconverted: I Made A Kierkegaardian Leap of Faith

How I Deconverted: My Closest, and Seemingly “Holiest”, Friend Came Out As Gay

How I Deconverted: My Closeted Best Friend Became A Nihilist and Turned Suicidal

How I Deconverted: Nietzsche Caused A Gestalt Shift For Me (But Didn’t Inspire “Faith”)

As I Deconverted: I Spent A Summer As A Christian Camp Counselor Fighting Back Doubts

How I Deconverted: I Ultimately Failed to Find Reality In Abstractions

A Postmortem on my Deconversion: Was it that I just didn’t love Jesus enough?

When I Deconverted:

When I Deconverted: I Was Reading Nietzsche’s “Anti-Christ”, Section 50

When I Deconverted: I Had Been Devout And Was Surrounded By The Devout

When I Deconverted: Some People Felt Betrayed

When I Deconverted: I Was Not Alone

The Philosophical Key To My Deconversion:

Apostasy As A Religious Act (Or “Why A Camel Hammers the Idols of Faith”)

When I Deconverted: Some Anger Built Up

After I Deconverted:

After I Deconverted: I Was A Radical Skeptic, Irrationalist, And Nihilist—But Felt Liberated

After My Deconversion: I Refuse to Let Christians Judge Me

After My Deconversion: My Nietzschean Lion Stage of Liberating Indignant Rage

Before I Deconverted:

Before I Deconverted: My Christian Childhood

Before I Deconverted: Ministers As Powerful Role Models

Before I Deconverted: I Was A Teenage Christian Contrarian

Before I Deconverted, I Already Believed in Equality Between the Sexes

Before I Deconverted: I Dabbled with Calvinism in College (Everyone Was Doing It)

How Evangelicals Can Be Very Hurtful Without Being Very Hateful

Before I Deconverted: My Grandfather’s Contempt

How I Deconverted:

How I Deconverted, It Started With Humean Skepticism

How I Deconverted, I Became A Christian Relativist

How I Deconverted: December 8, 1997

How I Deconverted: I Made A Kierkegaardian Leap of Faith

How I Deconverted: My Closest, and Seemingly “Holiest”, Friend Came Out As Gay

How I Deconverted: My Closeted Best Friend Became A Nihilist and Turned Suicidal

How I Deconverted: Nietzsche Caused A Gestalt Shift For Me (But Didn’t Inspire “Faith”)

As I Deconverted: I Spent A Summer As A Christian Camp Counselor Fighting Back Doubts

How I Deconverted: I Ultimately Failed to Find Reality In Abstractions

A Postmortem on my Deconversion: Was it that I just didn’t love Jesus enough?

When I Deconverted:

When I Deconverted: I Was Reading Nietzsche’s “Anti-Christ”, Section 50

When I Deconverted: I Had Been Devout And Was Surrounded By The Devout

When I Deconverted: Some People Felt Betrayed

When I Deconverted: I Was Not Alone

The Philosophical Key To My Deconversion:

Apostasy As A Religious Act (Or “Why A Camel Hammers the Idols of Faith”)

When I Deconverted: Some Anger Built Up

After I Deconverted:

After I Deconverted: I Was A Radical Skeptic, Irrationalist, And Nihilist—But Felt Liberated

After My Deconversion: I Refuse to Let Christians Judge Me

After My Deconversion: My Nietzschean Lion Stage of Liberating Indignant Rage