[Read about Sartre, Camus, Warhol, Hitchcock, and Heidegger in the “Famous Atheists Who Weren’t Atheists” archive.]

David Tracy’s Blessed Rage for Order introduced me to what would subsequently become one of my very favorite poems:

“The Idea of Order at Key West”

[Listen to Stevens reading it here]

She sang beyond the genius of the sea.

The water never formed to mind or voice,

Like a body wholly body, fluttering

Its empty sleeves; and yet its mimic motion

Made constant cry, caused constantly a cry,

That was not ours although we understood,

Inhuman, of the veritable ocean.The sea was not a mask. No more was she.

The song and water were not medleyed sound

Even if what she sang was what she heard.

Since what she sang was uttered word by word.

It may be that in all her phrases stirred

The grinding water and the gasping wind;

But it was she and not the sea we heard.For she was the maker of the song she sang.

The ever-hooded, tragic-gestured sea

Was merely a place by which she walked to sing.

Whose spirit is this? we said, because we knew

It was the spirit that we sought and knew

That we should ask this often as she sang.If it was only the dark voice of the sea

That rose, or even colored by many waves;

If it was only the outer voice of sky

And cloud, of the sunken coral water-walled,

However clear, it would have been deep air,

The heaving speech of air, a summer sound

Repeated in a summer without end

And sound alone. But it was more than that,

More even than her voice, and ours, among

The meaningless plungings of water and the wind,

Theatrical distances, bronze shadows heaped

On high horizons, mountainous atmospheres

Of sky and sea.It was her voice that made

The sky acutest at its vanishing.

She measured to the hour its solitude.

She was the single artificer of the world

In which she sang. And when she sang, the sea,

Whatever self it had, became the self

That was her song, for she was the maker. Then we,

As we beheld her striding there alone,

Knew that there never was a world for her

Except the one she sang and, singing, made.Ramon Fernandez, tell me, if you know,

Why, when the singing ended and we turned

Toward the town, tell why the glassy lights,

The lights in the fishing boats at anchor there,

As night descended, tilting in the air,

Mastered the night and portioned out the sea,

Fixing emblazoned zones and fiery poles,

Arranging, deepening, enchanting night.Oh! Blessed rage for order, pale Ramon,

The maker’s rage to order words of the sea,

Words of the fragrant portals, dimly-starred,

And of ourselves and of our origins,

In ghostlier demarcations, keener sounds.

Stevens is considered among the greatest of Modernist poets. Like most of his contemporaries he experienced a deep crisis of faith. His Presbyterian upbringing didn’t stand up to the double-challenge of post-Kantian philosophy and Darwinism. Like in the poem above the rest of his work is marked with a vague nostalgia for “more than that.”

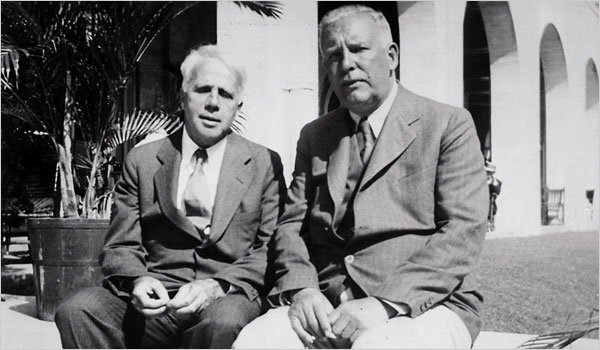

But the story doesn’t end there. There’s a last minute Hail Mary. You can read one version of the story here and Dana Gioia’s version toward the end of this article.

Helen Vendler, herself a lapsed Catholic besides being a widely published academic popularizer who’s written several books on Stevens (see: Words Chosen Out of Desire), has led the charge denying the conversion. That’s understandable, because it’s difficult to reconcile the image of a modernist iconoclast with the picture of a dying man who wanted to write a poem about a pope whose heart broke at his failure to stop World War I.

But the veritable ocean of the internet has turned up this response to Vendler’s questioning of the episode:

Dear Helen Vendler, I didn’t expect you to agree with everything I put down in my letter to you. It is disturbing, however, when you ignore the testimony of Dr. Edward Sennett (in charge of the Radiology Dept. at St. Francis Hospital when Stevens was admitted both times [1955]) and the Sisters with whom I talked in 1977 (and later) who believed Fr. Hanley’s account. They never spoke of any kind of forgetfulness or memory loss on Fr. Hanley’s part, whether noble (when one intentionally does not remember injuries, mischief, etc.) or unmeant (when one unintentionally cannot remember things owing to trauma, confusion or some other mental impairment). What provoked me NOT to visit Fr. Hanley in 1977 was their testimony that his account in 1955 was credible and that they believed Stevens was baptized. The Sisters had no reason to doubt Hanley’s word, one of whom worked with him and knew him quite well. You seem to want to ignore that. Do you really believe they were ALL taken in by Fr. Hanley’s ‘forgetfulness,’ by his ‘mental impairment,’ in 1977, when he was alive, retired, and in touch with them? (He lived only a half hour away from them!) Dr. Sennett was too sharp a person and knew the Sisters too well to believe they were being deluded and misled owing to Fr. Hanley’s ‘memory loss.’ Also, in your response, you ignore the fact that a number of priests in the past refrained from recording (in nearby parishes and hospitals) the baptisms of certain dying people. I myself, for example, remember baptizing two people and leaving their baptisms unrecorded on two different occasions. That is, I baptized two people (unconditionally and absolutely), gave them Communion, and didn’t record their baptisms in a nearby parish or at the hospital – for many reasons, not the least being that the dying person wanted no Catholic funeral and preferred that his/her ‘reception’ remain private (i.e., between himself/herself and God). I mentioned this in my first letter. Such private baptisms did occur in New England and elsewhere! (Today, of course, federal law and new legislation requires that some sort of record of a person’s baptism be kept in the hospital as part of the deceased person’s medical history. But that was not always the case in the past. And it is anyone’s guess as to whether priests abide by those rules today; they pick and chose so freely.) Finally, to assume that because ‘nothing in his [Stevens’] poetry or prose suggests any wish to be a member of any church’ he therefore could never have requested a private baptism flies in the face of so many ‘hour of death’ accounts of the dying, many of whose private testimonies, disclosures, groundless terrors contradict the reckonings and calculations erected or founded on their earlier lives (and, in this case, the person’s writings). The dying often believe for themselves; not for another person or for the sake of some book they wrote. Any person who has witnessed the dying also knows that they ‘say’ and disclose their sentiments (in words and gestures) better than the witnesses or those around them can, foolish cliches and all. In conclusion, I don’t think this response to your letter will dissuade you from holding your own belief that Fr. Hanley was forgetful, etc. Indeed, reasoning further against your opinion in this matter would be like fighting against a shadow – all-consuming, exhausting without affecting the shadow. I also sincerely believe you can’t change. As a critic, you have too much invested in your opinion. (One of my colleagues lent me her THE MUSIC OF WHAT HAPPENS to read. In that book you are quite adamant about Hanley on page 80.) However, based on Dr. Sennett’s and the Sisters’ propriety of feeling for Fr. Hanley and their belief that he was telling the truth in 1977 as he was in 1955, I do believe Stevens was baptized privately (though in academic journals his baptism will always be lightly condemned, censured, or laid aside as ‘inconsistent’ with his writings). I also believe that the baptism should never have been made public. Stevens was a great ‘unnamer,’ to quote Harold Bloom, and Fr. Hanley should have left his baptism unnamed, as it were, anonymous, like a ‘blindness cleaned.’ Sincerely, (Fr.) James Chichetto, C.S.C.

I’ll leave you with a poem whose lines furnished the title of the above collection.

“Of Mere Being”

The palm at the end of the mind,

Beyond the last thought, rises

In the bronze decor,A gold-feathered bird

Sings in the palm, without human meaning,

Without human feeling, a foreign song.You know then that it is not the reason

That makes us happy or unhappy.

The bird sings. Its feathers shine.The palm stands on the edge of space.

The wind moves slowly in the branches.

The bird’s fire-fangled feathers dangle down.

Even just from what you’ve read of Stevens in this post, doesn’t it seem appropriate that his Catholic demarcations remained ghostly? How ironic that the skeptics among us would have to fabricate comforting stories (a favorite Stevens theme) in order to make our skepticism more certain!

And even if Stevens remained an atheist, the following passage from Simone Weil’s Gravity and Grace is an interpretation of skepticism that is much more skeptical than Vendler’s comfortable reassurances:

“Religion in so far as it is a source of consolation is a hindrance to true faith; and in this sense atheism is a purification. I have to be an atheist with that part of myself which is not made for God. Among those in whom the supernatural part of themselves has not been awakened, the atheists are right and the believers wrong.”

Fides confusa is a concept that would have tickled the author of supreme fictions with its ambiguity.