This is a continuation of yesterday’s post on Catholicism and contemporary French philosophy. If you’re curious about how continental philosophy is faring in American universities take a look at the following link from Philosophy News.

The debate whether theology has a place in phenomenology has preoccupied the minds of France’s best thinkers for the better part of the last two, maybe three, decades. The books I list below are a testament to the sort of hearty debate that’s taking place there. The God debate does not seem to be dead for the French, not even for thinkers who are atheists. The repressed has come back with a vengeance.

Dominique Janicaud typifies the objections in the debate by stressing the methodological atheism of phenomenology (really, any kind of philosophy), at least since Heidegger and Sartre, because it allows for a clean, unpolluted, approach to philosophy as separated from theology. It’s fascinating how someone from a culturally Catholic country would want to go the Reformation route of keeping grace separated from nature. I believe Janicaud is sincere, or at least attempts to look sincere, when he to gives a partial nod to theology in his concluding report on the theological turn:

“We have not had any other design than to draw out these several traits and to recall an insurmountable difference: phenomenology and theology make two. To see as much and to understand it better, certainly it is not out of place here to draw attention, finally, to two thoughts equally worthy of being meditated upon in their very divergence. On the theological side, Luther ‘Faith consists in giving oneself over to the hold of things we do not see.’ On the phenomenological side, Goethe, ‘There is nothing to look for behind the phenomena; they are themselves the doctrine.'”

What he doesn’t seem to realize is that he’s reproducing “Two Kingdoms” Lutheran/Calvinist reading of nature and grace that doesn’t square with much of the Christian tradition. I’ve written several pieces on the work Dariusz Karlowicz has done on philosophy as a way of life as it was taken up by the Church Fathers here. Before the nominalists and the Reformation philosophy was never divorced from theology. In fact, the Greek tradition of philosophy under Plato, Aristotle, and the Stoics consisted of spiritual exercises in quasi monastic communities–again, see my posts on Karlowicz.

What’s more, the French phenomenological school owes some of its roots to the engagement of Jean-Luc Marion with Hans Urs von Balthasar. Marion’s use of von Balthasar’s work is most up front in his early work The Idol and Distance where he frequently directly cites von Balthasar. Marion was the co-founder of the French edition of Communio along with Remi Brague (whose work is a frequent topic of discussion on Cosmos) and Henri de Lubac at the behest of von Balthasar.

Henri de Lubac is significant to this debate, because in books such as A Primer on Nature and Grace andThe Mystery of the Supernatural he worked to recover this earlier pre-modern perspective of polluting philosophy with theology and vice-versa. As evidenced in John Milbank’s book, The Suspended Middle, de Lubac also influenced the work of Radical Orthodoxy.

Given how much the narrative of Catholic intellectual decline is in fashion of late (there’s the Elie verison, the Boyagoda version, and Gioia’s most recent version) there’s no sign of a Catholic letup in phenomenology.

If we are after setting up first things first, then Catholics are in a pretty darn good position by setting the pace in philosophy. If you’ve read my commentaries on Elie’s and Boyagoda’s articles then you know I don’t buy the crisis narrative at all. One of these days I’ll tackle Gioia’s article in First Things. In the meantime you can look at the embarrassment of riches in contemporary Christian writing here and here.

Before I go off on too many tangents, here’s what the French experiment in stretching out phenomenology into theology has produced from both Catholics and those non-believers who’ve been pulled into the convergence between the two:

Defiant, moving, and vastly challenging, I Am the Truth: Toward a Philosophy of Christianity contains intellectual drama of the highest order. . . The magnificence and great strangeness of the book, a sweeping blast at the modern history of Western civilization leveled from the perspective of the lost world of a Christian critique of representation, will jolt English-language readers.

The Metamorphosis of Finitude starts off from a philosophical premise: nobody can be in the world unless they are born into the world. It examines this premise in the light of the theological belief that birth serves, or ought to serve, as a model for understanding what resurrection could signify for us today. After all, the modern Christian needs to find some way of understanding resurrection, and the dogma of the resurrection of the body is vacuous unless we can relate it philosophically to our own world of experience.

Stanislas Breton presents the nothingness of the cross in its infirmity and paradoxical power. Blending the poetic with the philosophical, faith with interrogation, mystical and practical, ancient and new, he seeks to lift the cross from its imprisonment in ontologies of abundance and in a history of compromise. The Word and the Cross distills the meditation of a thinker in his prime on the possibility of the Christian and Christianity to find within a principle of a critique and source of renewal.Breton draws first upon Scripture, examining the way in which the cross has been present in our world, beginning with Paul’s preaching of it as Logos, folly (moria), and power (dunamis). In a startlingly original interpretation, Breton first interrogates the emergence of the cross as Sign of Contradiction in the world of Greek and Jew and then traces its destiny in politics, in theology and in the poignant theater of the fools of Christ.

Adoration is the second volume of the Deconstruction of Christianity, following Dis-Enclosure. The first volume attempted to demonstrate why it is necessary to open reason up not to a religious dimension but to one transcending reason as we have been accustomed to understanding it; the term “adoration” attempts to name the gesture of this dis-enclosed reason. In this book, Jean-Luc Nancy goes beyond his earlier historical and philosophical thought and tries to think-or at least crack open a little to thinking-a stance or bearing that might be suitable to the retreat of God that results from the self-deconstruction of Christianity. Adoration may be a manner, a style of spirit for our time, a time when the “spiritual” seems to have become so absent, so dry, so adulterated.

In Nietzsche and the Shadow of God (Nietzsche et l’ombre de Dieu), his study of Nietzsche’s integral philosophical corpus, Franck revisits the fundamental concepts of Nietzsche’s thought, from the death of God and the will to power, to the body as the seat of thinking and valuing, and finally to his conception of a post-Christian justice. The work engages Heidegger’s interpretation of Nietzsche’s destruction of the Platonic-Christian worldview, showing how Heidegger’s hermeneutic overlooked Nietzsche’s powerful confrontation with revelation and justice by working through the Christian body, as set forth in the Epistles of Saint Paul and reread both by Martin Luther and by German Idealism.

Phenomenology and the “Theological Turn” brings together the debate over Janicaud’s critique of the “theological turn” represented by the works of Emmanuel Levinas, Paul Ricœur, Jean-Luc Marion, Jean-François Courtine, Jean-Louis Chrétien, and Michel Henry.

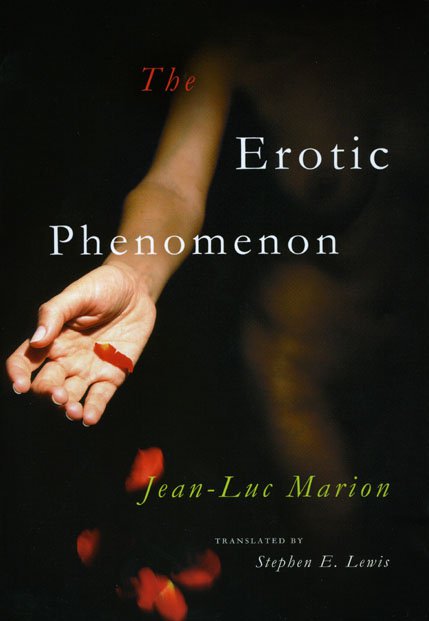

While humanists have pondered the subject of love to the point of obsessiveness, philosophers have steadfastly ignored it. The word philosophy means “love of wisdom,” but the absence of love from philosophical discourse is curiously glaring. In The Erotic Phenomenon, Jean-Luc Marion attends to this dearth with an inquiry into the concept of love itself. Marion begins with a critique of Descartes’ equation of the ego’s ability to doubt with the certainty that one exists. We encounter love, he says, when we first step forward as a lover: I love therefore I am, and my love is the reason I care whether I exist or not. This philosophical base allows Marion to probe several manifestations of love and its variations, including carnal excitement, self-hate, lying and perversion, fidelity, the generation of children, and the love of God. Throughout, Marion stresses that all erotic phenomena stem not from the ego as popularly understood but instead from love.

If all of this hasn’t been enough for you, one of my friends has a forthcoming book entitled Praying to a French God.

Don’t forget to read through yesterday’s detailed and essential introduction to this series here. Finally, here are the other Cosmos TOP10s.