Once in a while you run across a thread that nearly makes all those hours you waste on facebook somewhat almost worthwhile.

A couple of days ago I spent some time belittling the Nova story about cosmology I found in my news feed (I felt bad about it later). My attitude grew out of how the nice PBS people went for the jugular in their posting of the story. The post led with, “Ready to have your mind blown? We might be living in a membrane around the event horizon of a collapsed hyperdimensional star that gave birth to the universe.” My mind was still intact and not too stimulated after reading the rather tame full story here.

Out of sheer cosmic boredom my next mission will consist of taking apart the “Cosmos: A Space-Time Odyssey” ship of the imagination, but for different reasons, purely as something of a trained historian.

Ultimately I’m partial to Wittgenstein’s attitude from the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus about all such cosmological discoveries. He says, “Once we have answered all questions of science there is still the matter of how to live life.” Walker Percy said something along these lines in one of the five or so subtitles to his classic Lost in the Cosmos, “Why is it that of all the billions and billions of strange objects in the Cosmos–novas, quasars, pulsars, black holes–you are beyond doubt the strangest?” I’ll return to how these pertain to our (or maybe just mine?) cosmic ennui.

It was easy to dismiss the membrane, since it was so overblown. Yet, it was impossible to ignore the personal urgency and significance given to another recent scientific achievement by Matthew J. Peterson of the de Koninck Project. Here is his facebook reaction to an Atlantic piece that was rather enthusiastically titled, “We Made It: Humanity Has Arrived at Interstellar Space.” Matthew says,

“We built something that is now 12 billion miles away, recording the sound of the Sun exploding as heard beyond the solar winds in interstellar space. And yet we have no songs or poems about the greatest achievements in the exploration of the universe that keep on growing; we are quite dead to it… Why?”

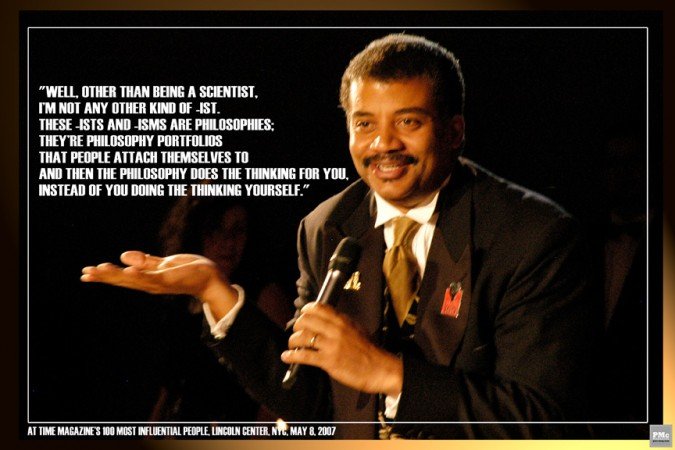

So why doesn’t that generate excitement from humanists and theologians? Aren’t they getting lost in the cosmos even more by ignoring it? Don’t they cede ground to atheist cosmic-mystics like Carl Sagan, Richard “the Mild” Dawkins, Neil de Greese Tyson, Bill Nye, and Barbara Hubbard-Marx?

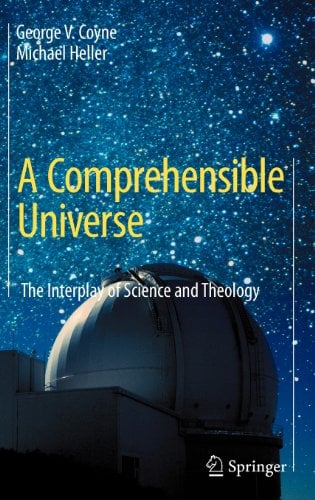

Actually, this hasn’t been entirely ignored by theologians. There are people working on these questions in theology, people like Fr. Michael Heller, Conor Cunningham, George Coyne, SJ and Thomas F. O’Meara, OP. They’ve been working out the implications of evolution, space travel, cosmology, and even extraterrestrials. Most of them are scientists of the highest rank. In this they are merely part of a long tradition of orthodox believers who’ve made nearly all the most fundamental contributions within many scientific fields.

So let’s not fall into “declinism” too quickly. Our urge for instant gratification forgets how it takes genuine scientific discoveries, and other intellectual innovations, about two to three hundred years to filter into the popular imagination. And you thought Rome is slow!

For example, in the Land of Urlo Czeslaw Milosz welcomes the discoveries of modern physics, because he believes they open up to Christian theology in a way that wasn’t possible in a mechanistic universe run by an expandable watchmaker. He also notes we’ve barely absorbed Newton, so it’s no surprise that both Einstein and the Copenhagen School of quantum physics haven’t trickled down into the popular imagination.

Let’s be patient.

Be that as it may, there is also the problem of relation when it comes to getting aroused by vacuums twelve billion miles away even if “we’ve made it.” Poetic utterances require us to have something at-hand in order to be capable of intuitions (the original meaning of ποίησις is “to make”).

Therefore, if you want to make something of the moral law within, or the starry skies above, then your intuitions of both are fairly close at hand. All you have to do is to step outside and look (if there isn’t too much light pollution where you live), or look inside (if you’re not a shallow bastard like me). The same goes with great historical discoveries. Testimonies are at hand in personal and historical accounts of the events. The same can’t be said for the abstract constructs of modern physics or interstellar travel. That’s why they leave us cold. Heck, even as great a poet as W.H. Auden couldn’t relate much to the moon-landing:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ymDPQodemU4

What’s more, we should temper our lamentations at the loss of teleology since Francis Bacon. We should remember that the Roman Empire’s reliance upon the Greek model of the world/cosmos as a source of wisdom eventually, right around the time of Christ, became a burden.

As Remi Brague reminds us in The Wisdom of the World, one of the main appeals of Christianity was its marked ambivalence toward the world as a source of wisdom. After all, it’s amusing to read your future in the horoscope once ever so often. But what if you believed it contained the literal itinerary of your next week? How hellish would that be? We might be made from stardust, but thank God we are no longer bound by an idolatry of stars.

There is a kind of comfort in being lost in a comprehensible cosmos while knowing we cannot be reduced to easily digestible to scientific formulas. These mysteries go back to another one of Walker Percy’s subtitles for Lost in the Cosmos, “How it is possible for the man who designed Voyager 19, which arrived at Titania, a satellite of Uranus, three seconds off schedule and a hundred yards off course after a flight of six years, to be one of the most screwed-up creatures in California-or the Cosmos?”

All in all, the matter of theology should be the encouraging of personal transformation as both Larry Chapp and Michael J. Buckley have argued in books that made my TOP 10 list of recent books in theology. Collecting objective data about the universe will not effect the total subjective transformation that the best theology demands from you through spiritual exercises; you can be a dickhead and a great scientist.

But, if you do chance your own life, you’ll also see the universe around you differently. Which reminds me…

Space is too cold for me to care. Did you notice how Neil deGrasse Tyson was aware of just that?

He resurrected the ghost of Sagan at the end of the first episode of his version of “Cosmos” in order to warm up the cold corpse of the universe. He also spent an inordinate amount of time hoping, contrary to hard evidence, that there’s life on Mars (or that there’s a multiverse).

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v–IqqusnNQ

All of that is understandable.