Carl Schmitt who was one of those extremely bad Catholics like Heidegger who played a part in Hitler’s regime. In some circles Schmitt became known as the “Crown Jurist of the Third Reich.”

This arch-conservative thinker ironically made a comeback through the New Left. You can see his influence on Derrida (that Catholic phenomenology enabler) in his The Politics of Friendship; for Schmitt politics is the process of the state creating a friend/enemy dichotomy by designating clearly defined enemies. There is also the much discussed Homo Sacer by Giorgio Agamben on what’s called the state of exception, also borrowed from the Crown Jurist. Agamben has frequently criticized America for resorting to this suspension of the law especially in the aftermath of its Iraq wars.

As you can see, his legacy is not one of pure evil, despite the nickname. He ran afoul with the Nazi Party in 1937 after being exposed as an opportunist–a fake anti-Semite and a Catholic. I must admit, I’m not sure what’s worse: a) being a real Nazi, or b) pretending to be one to advance your career.

Fast forward to today’s headlines…. According to Timothy Snyder, author of Badlands (previously mentioned in a post about 9/1/39 here), and America’s foremost expert on Eastern Europe, Schmitt is also making a more uncomfortable comeback on the Hard Right. He explains the source of this return in “Fascism, Russia, and Ukraine“:

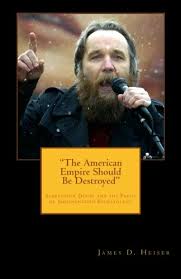

The Eurasian ideology draws an entirely different lesson from the twentieth century. Founded around 2001 by the Russian political scientist Aleksandr Dugin, it proposes the realization of National Bolshevism. Rather than rejecting totalitarian ideologies, Eurasianism calls upon politicians of the twenty-first century to draw what is useful from both fascism and Stalinism. Dugin’s major work, The Foundations of Geopolitics [not available in English, but his more recent The Fourth Political Theory is], published in 1997, follows closely the ideas of Carl Schmitt, the leading Nazi political theorist. Eurasianism is not only the ideological source of the Eurasian Union, it is also the creed of a number of people in the Putin administration, and the moving force of a rather active far-right Russian youth movement. For years Dugin has openly supported the division and colonization of Ukraine.

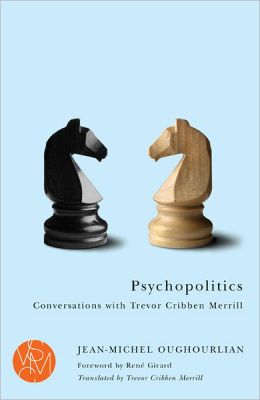

Jean-Michel Oughourlian falls into neither the New Left, nor Hard Right camps, yet he is yet another important thinker who is utilizing Schmitt’s theories. He isn’t exactly Schmittian in his own intellectual commitments. He’s a Girardian who has followed Girard’s lead in Battling to the End in applying mimetic theory to current world political events. In a discussion of state terrorism in his recently published Psychopolitics he explains what Truman and MacArthur got right on Schmitt’s terms (this passage is part of a longer discussion of Schmitt’s Concept of the Political). This discussion is mostly a setup for explaining how Bush’s strategy in Iraq departed from their prudence. I have not figured out what he means by his comments about the A-bomb as being the first instance of “state terrorism,” but that’s not germane to our discussion (stay on topic combox warriors!):

The first example of state terrorism was President Truman’s decision to use the atomic bomb in 1945: the Japanese army was far from being entirely destroyed, the American losses were enormous, and the “conventional” war could have lasted another 5 to 10 years. So Truman decided to terrorize the Japanese (and perhaps also the Russians) and this objective was achieved by unleashing the apocalypse on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Faced with this event, which was unprecedented in the history of mankind, Emperor Hirohito and the Japanese government understood that all the laws of conventional warfare had been obliterated, and they were totally terrified at the prospect of a generalized apocalypse, they surrendered.

Here I would like to stress the enormous political merit of General MacArthur, who returned at once to the rules of conventional warfare: showing respect for the emperor and respect for the defeated enemy. He did not destroy the Japanese administrative apparatus and kept the emperor’s position and function intact, thereby ensuring the respect and confidence of the population.

I insist on the merit and political wisdom of General MacArthur so as to bring out by contrast the crude political error committed by George W. Bush when he destroyed the administrative, political, and police apparatus of Iraq after the defeat of Saddam Hussein, plunging the country into anarchy and chaos, opening the way to partisan warfare, insurrectional warfare, and to the development of the second variety of terrorism [“popular terrorism”] . . .

Philip Jenkins discusses the same disastrous lack of a political vision for Iraq in “Saddam’s Strategy Against ISIS.” His article puts in contetxt of America’s latest war in the region against ISIS:

Today’s Islamic State pursues an extremist ideology in which there are literally no limits to cruel or outright evil behavior. The only enemy they have to fear is death, and they have been taught to welcome this. Short of introducing some mighty new deterrent factor, conventional military operations against them are wildly unlikely to succeed. Quite the contrary, endemic wars will generate ever more fanatics.

In theory, a recipe does exist for decisively ending the Islamists’ run of victories. Through means of collective and family punishment, which explicitly targets individuals who have done no wrong, governments and armies must introduce a brutal deterrent regime that will even outweigh the massive temptations of martyrdom and an instant road to Paradise.

No U.S. government would ever introduce such a policy, and if it did, it would cease to be anything like a democratic society. The U.S. could only adopt such avowedly terrorist methods following a wrenching national debate about issues of individual and group responsibility, and the targeting of the innocent. Could any U.S. government avowedly take hostages? We would be looking at a fundamental transformation of national character, to something new and hideous. But what other solutions could or would be possible?

Given that U.S. administrations are not going to fight the Islamic State by the only effective means available—and thankfully, they aren’t—why are they engaging in this combat in the first place?

Why start a war when you don’t plan to win it?

That’s the multi-billion dollar Schmittian question. Are Americans willing to treat the enemy as vermin that must be exterminated? These are the rules on the ground. Can Americans submit to them? If not, what are they doing there? How much Schmitt can we handle?