The term genocide seems ancient. It is actually a clumsy Greek-Latin hybrid coined by a Polish Jew between 1943 and 1944 when Polish gentiles were reporting about the Holocaust to Roosevelt who merely shrugged his shoulders. Genocide’s “creator,” Raphael Lemkin used the Armenian Genocide as the baseline for describing the Holocaust.

The first published instance of the term is probably his book Axis Rule in Occupied Europe. The history of the Armenian Genocide, so important to Lemkin’s thought, is little known today because of the effectiveness of the Turkish secular nation-state in executing its murderous policies and then winning the politics of history war by systematically obfuscating the significance and extent of their atrocities. Their success reportedly led Hitler to say, “Who remembers the Armenians today?”

Recent scholarship is catching up with the significance of Lemkin’s contribution to intellectual history. The recent publication of The Origins of Genocide: Raphael Lemkin as a Historian of Mass Violence attempts to rectify our ignorance:

This year the United Nations celebrated the ‘Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide’, adopted in December 1948. It is time to recognize the man behind this landmark in international law. At the beginning were a few words: “New conceptions require new terms. By ‘genocide’ we mean the destruction of a nation or of an ethnic group”. Rarely in history have paradigmatic changes in scholarship been brought about with such few words. Putting the quintessential crime of modernity in only one sentence, Raphael Lemkin (1900-1959), the Polish Jewish specialist in international law, not only summarized the horrors of the National Socialist Crimes, which were still underway, when he coined the term “genocide” in 1944, but also influenced international law. As the founding figure of the UN Genocide Convention Lemkin is finally getting the respect he deserves. Less known is his contribution to historical scholarship on genocide. Until his death, Lemkin was working on a broad study on genocides in the history of humankind. Unfortunately, he did not manage to publish it. The contributions in this book offer for the first time a critical assessment not only of his influence on international law but also on historical analysis of mass murders, showing the close connection between both.

Oddly enough, no mention is made about the importance of Armenia for the development of his thought in the blurb above. That’s something I learned while listening to an NPR program yesterday:

The word genocide was not coined until 1944 by Raphael Lemkin, a Polish lawyer who combined the Greek word “genos,” meaning race or family, with the Latin word “-cidere,” for killing, to describe the events of the Holocaust.

As a teenager, he was drawn to the story of what happened to the Armenians in the Ottoman Empire after reading about a survivor of the atrocities. And in interviews in the 1940s he described the events as the Armenian genocide.

The Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, which describes the events as a genocide, says Lemkin’s “early exposure to the history of Ottoman attacks against Armenians, anti-Semitic pogroms, and other cases of targeted violence as key to his beliefs about the need for the protection of groups under international law. Inspired by the murder of his own family during the Holocaust, Lemkin tirelessly championed this legal concept until it was codified in the United Nations Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide in 1948.”

The 1.5 million victims of the Armenian Genocide were commemorated today by the Armenian Church by being declared saints. The criminal obstinacy of the secular Turkish government government is best demonstrated by its moving up the celebrations of its founding as a secular nation-state to today in order to compete with the Armenian commemoration.

Let’s not let Hitler have the last word. May this story also disabuse us of the secular myth of religious violence.

===========================================

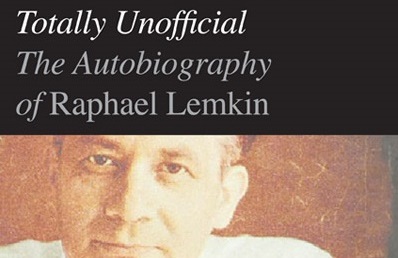

You can read more about Lemkin in his autobiography (sadly, he died alone, in poverty) or in Raphael Lemkin and the Struggle for the Genocide Convention.

For more on the Armenian Genocide see: They Can Live in the Desert but Nowhere Else and The Burning Tigris.