I forced myself to reflect upon the importance of getting our pictures of God sorted out in a previous post by briefly engaging what Justice Scalia said about God and state in Louisiana. It would be easy to say Scalia Santo Subito after his showboating in a St. Thomas More hat during the Obama inaugural if, if we didn’t pay attention to his theological language. The theological language neither matches the bombast of the headware, nor the demands of orthodoxy. Scalia might be talking about the Judeo-Christian God, but he does so in radically inadequate ways.

Nietzsche’s death-of-God is less a historical event where the Divinity is literally assassinated, but more of a linguistic and existential situation where our notions of God are completely inadequate to the reality they aim for and to the demands that reality makes upon us. One such example is that Scalia line I cited yesterday:

God takes care of little children, drunkards and the United States of America, I think that’s true. God has been very good to us. One of the reasons God has been good to us is that we have done him honor.

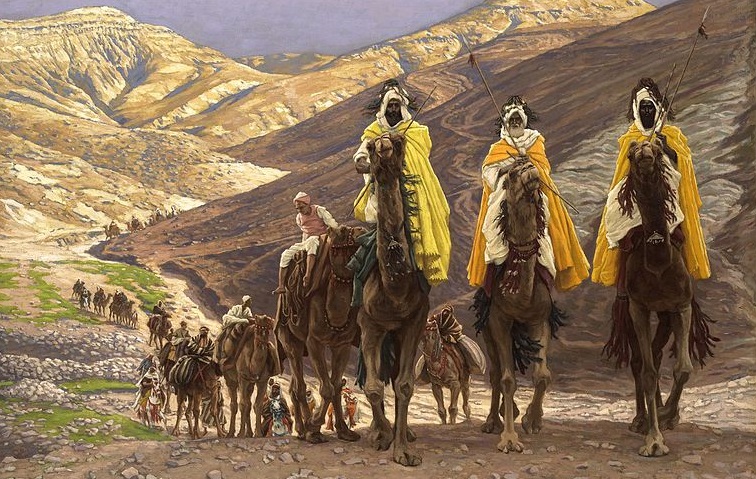

Honor is a peripheral value to the Bible’s theologies. It is much more important for Greeks, the myths of modern nation-states, and, more recently, identity politics. On the other hand, hospitality is much more fundamental to the message of the Bible. In his A History of the Church in Latin America: Colonialism to Liberation Enrique Dussel demonstrates how hospitality, the event at the center of the Feast of the Three Kings, is so important that it ties directly to what the West Experiences as the Death of God:

The authentic epiphany of the Word of God is that word spoken by the poor man who says, “I am hungry!” And only the person who hears this cry of the poor and who is in effect a nonbeliever, a negator of the system, can hear the genuine Word of God. God has not died, but God’s epiphany has been assassinated in the Indian, the African, and the Asian. Therefore God can no longer reveal himself Abel died in the deification of Europe, of the “center ,” and God is now hidden. The norm of interpretation that has been revealed is: “I was hungry and you never gave me food. …Then it will be their turn to ask, ‘Lord, when did we see you hungry …?’ ”(Matt. 25:42-44).36 Now by the death of the deification of Europe faith can be born in the breast of the “peripheral” poor. Faith in God mediated by the poor is the new manifestation of God in history, and faith becomes reality not by the writing of theological or theoretical treatises on “the death of God,” but by means of applied justice.

Why are the poor so central to the Gospel message? To avoid scandal after quoting someone who practices something called a “Philosophy of Liberation” I’ll quote St. John Paul II from his homily during the canonization of St. Edith Stein.

The following passage from the homily makes it clear that Europe didn’t only kill the Stranger in Latin America, but also on its own territories and very recently at that (not to mention during the forced conversions of the European continent, a religious colonizing practiced on the future colonizers before colonialism):

Dear brothers and sisters! Because she was Jewish, Edith Stein was taken with her sister Rosa and many other Catholic Jews from the Netherlands to the concentration camp in Auschwitz, where she died with them in the gas chambers. Today we remember them all with deep respect. A few days before her deportation, the woman religious had dismissed the question about a possible rescue: “Do not do it! Why should I be spared? Is it not right that I should gain no advantage from my Baptism? If I cannot share the lot of my brothers and sisters, my life, in a certain sense, is destroyed”.

From now on, as we celebrate the memory of this new saint from year to year, we must also remember the Shoah, that cruel plan to exterminate a people — a plan to which millions of our Jewish brothers and sisters fell victim. May the Lord let his face shine upon them and grant them peace (cf. Nm 6:25f.).

For the love of God and man, once again I raise an anguished cry: May such criminal deeds never be repeated against any ethnic group, against any race, in any corner of this world! It is a cry to everyone: to all people of goodwill; to all who believe in the Just and Eternal God; to all who know they are joined to Christ, the Word of God made man. We must all stand together: human dignity is at stake. There is only one human family. The new saint also insisted on this: “Our love of neighbour is the measure of our love of God. For Christians — and not only for them — no one is a ‘stranger’. The love of Christ knows no borders”.

That Christian nation that Michael Baxter discussed in yesterday’s post knows no borders. It invites strangers like the Magi to epiphanies as strange as a swaddled child, pooping and breastfeeding.

This Christianity thing is truly strange.

Don’t kill it.

For more on the philosophy and theology of hospitality see my post on anatheism, or peruse Henri Cardinal de Lubac’s thoughts on the Death of God.

While I am employed part-time I am by no means rich. If you feel inclined to give to the stranger then you can donate through the PayPal button on this page.