Caillebot’s painting above is significant to me because in and through its simplicity the painting evokes a world of weight, depth, nobility, and solidity that’s been disappearing in the First World since World War II. It’s as if the West, appalled by the horrors of the War, opted for the world of phantasmagorias and abstractions that we now inhabit.

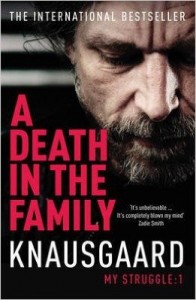

The following passage from Knausgaard’s stunning memoir-novel (movel?) My Struggle, Book 1 adumbrates a little of the world that’s been lost and how it can be seen in the change of painterly styles:

1 adumbrates a little of the world that’s been lost and how it can be seen in the change of painterly styles:

I didn’t know what it was about these [paintings] that made such a great impression on me. However, it was striking that they were all painted before the 1900s, within the artistic paradigm that always retained some reference to visible reality. Thus, there was always a certain objectivity to them, by which i mean a distance between reality and the portrayal of reality, and it was doubtless in this interlying space where it “happened”, where it appeared, whatever it was I saw, when the world seemed to step forward from the world. When you didn’t just see the incomprehensible in it but came very close to it. Something that didn’t speak, and that no words could grasp, consequently forever out of our reach, yet within it, for not only did it surround us, we were ourselves part of it, we were ourselves of it.

If paintings from before 20th century depict the world we lost, then the work of the recently deceased agnostic Polish philosopher and sociologist Zygmunt Bauman depicts our world, the world that followed upon that loss. Bauman is one of those rare intellectuals whose thought is immediately accessible to the general reader without losing any intellectual depth.

His Liquid Modernity might be the single best description of the world we inhabit where all that is solid melts into thin air. The center does not hold, but Bauman is a sure guide to understanding what all that means. What Liquid Modernity describes, and it is something I’ve briefly discussed before, is not an academic exercise, but something that affects not only the present, but also the collective future. I cannot recommend this work highly enough if you feel confused about the world we inhabit and where it is heading. If you can’t relate to this feeling of vertigo then you probably have some bigger problems.

But I don’t want to dwell on psychoanalyzing you, nor on the details of liquid modernity (which you can explore here); nor on Bauman’s period of zealous Stalinism (I believe in Kolakowski’s dictum from Metaphysical Horror, “A modern philosopher who has never once suspected himself of being a charlatan must be such a shallow mind that his work is probably not worth reading.”); instead, a couple days after Bauman’s death (I’m not a fan of the euphemism “passing,” because it lacks substance), I’d like to share the following passage from Of God and Man, since it hopes for a more humane future:

You are right (and deserve credit) when observing that, one way or the other, we somehow possess this world, and, from time to time, here and there, are even able to change at least a small part of it for the better. Given that this world of ours is still in the making, the act of its creation yet incomplete, and the work of continuing the creation and its completion has (to recall our earlier conversations) fallen to us, then it is right for us – as for any responsible host – to care for its well-being and attend to its goodness and beauty. I will repeat again Camus’ credo: there is beauty, and there are the humiliated. God grant that I never be unfaithful to the one or the other.

John Paul II, when already ill and approaching death, never stopped proclaiming to our world, devoured as it is by greed and resentment, hatred and insensitivity, that ‘God is love.’ You and I and many of our compatriots would gladly accept such a God; such a God we would find difficult –nay, impossible –to renounce, unless it was along with our humanity.

Beauty and poverty, these are the two properties of the incarnation, that are gathered up in the technical term kenosis, the self-emptying of a God who is beauty-itself. These then, beauty and poverty, are the concepts for addressing our bewilderment for the days without a why (see song below).

I’m reminded of two passages from the Liturgy of Hours. The first comes from a sermon by St. Basil the Great:

What, I ask, is more wonderful than the beauty of God? What thought is more pleasing and wonderful than God’s majesty? What desire is as urgent and overpowering as the desire implanted by God in a soul that is completely purified of sin and cries out in its love: I am wounded by love? The radiance of divine beauty is altogether beyond the power of words to describe.

But we are not left in a transcendent muteness, because that beauty, according to St. Augustine in one of his Homilies on First John, can be found in the poverty of the everyday humdrum (Knausgaard gets this too). This is what remains solid in a liquid modernity that perversely mirrors the inscrutability of God:

…As far as teaching is concerned, the love of God comes first; but as far as doing is concerned, the love of our neighbour comes first. Whoever sets out to teach you these two commandments of love must not commend your neighbour to you first, and then God, but God first and then your neighbour. You, on the other hand, do not yet see God, but loving your neighbour will bring you that sight. By loving your neighbour you purify your eyes so that they are ready to see God, as John clearly says: If you do not love your brother, whom you see, how can you love God, whom you do not see?

You are told “Love God”. If you say to me “Show me whom I should love”, what can I say except what John says? No man has ever seen God. But you must not think yourself wholly unsuited to seeing God: God is love, says John, and whoever dwells in love dwells in God. So love whoever is nearest to you and look inside you to see where that love is coming from: thus, as far as you are capable, you will see God.

So start to love your neighbour…

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=isgydm69YLE

You might also want to take a look at, Zygmunt Bauman: From Liquid Modernity to Theology.

Consider making a donation to this blog through the donation button on the upper right side of its homepage. Many thanks to all the souls who have already done so, or plan to do so in the future.

Stay in touch! Like Cosmos the in Lost on Facebook: