Here’s something you don’t see every day in The New York Times, a long and thoughtful look at the life and legacy of a saint.

On his knees, head bowed before bloodstained robes, a Polish man was deep in prayer.

He was worshiping in a chapel at the John Paul II Center in Krakow, a sprawling complex where relics of the former pontiff are displayed, including the clothes he was wearing when nearly killed by an assassin’s bullet in 1981.

An engineer, the man said he preferred to keep his prayers private and asked that only his first name, Wojciech, be used. But he was excited to talk about his beloved pope.

“Whenever I have a problem in my life, I come here to pray,” Wojciech said.

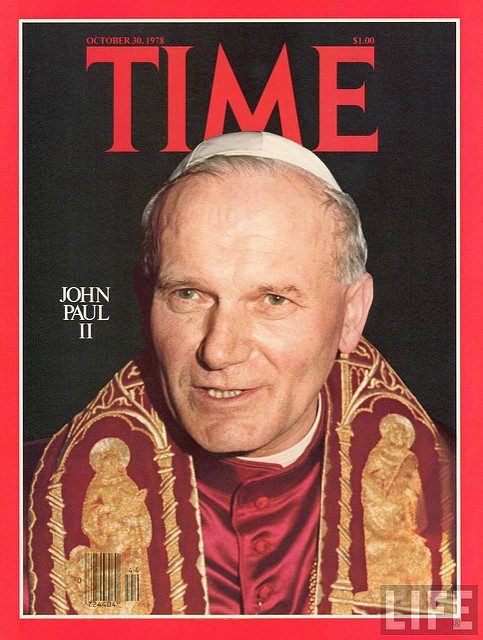

In a nation increasingly divided, one figure can still inspire solidarity among Poles: The man born Karol Jozef Wojtyla, who, in 1978, became John Paul II, the first non-Italian pontiff in 455 years.

The nation’s favorite son, he still looms large in Polish life more than 40 years after he was named Bishop of Rome.

From a towering 45-foot-tall statue depicting the pope with outstretched hands that overlooks the city of Czestochowa, to the relics distributed to churches throughout the country — including drops of his blood in more than 100 parishes — Poland is awash in tributes to the man commonly referred to as “Our Pope.”

But at a moment when the country finds itself torn by political conflicts that are cast by all sides as an existential battle for the nation’s soul, the legacy of John Paul II — a champion for both Poland and an integrated Europe — is the subject of dispute.

“For everyone, he remains a positive point of reference,” said Michal Luczewski, the program director for the Center on the Thought of John Paul II in Warsaw. “But there is a struggle over his legacy, with each side wanting to claim him as their own.”

For those on the political right, the pope is an inspiration in their battle against an increasingly secular Europe, Mr. Luczewski said.

Conservative voters, including many supporters of the governing Law and Justice party, believe they are carrying on the pope’s mission, particularly the fight against abortion — an issue that continues to be deeply divisive in this country with the most restrictive reproductive laws in Europe.

But on the other side, Poles who believe the Law and Justice party is doing great damage to the nation’s democratic institutions — including undermining the judiciary system and controlling the state news media — find forceful rebukes to the creeping authoritarianism in the life and teachings of John Paul II.

“The newest members of the democratic family, John Paul II hoped, ought to be a reminder to the older members of the family that freedom and truth, freedom and virtue, cannot be separated without doing serious damage to the democratic project,” George Weigel, the author of “Witness to Hope,” a biography of John Paul II, said in a recent speech in Warsaw.