David Russell Mosley

Ordinary Time

13 November 2014

The Edge of Elfland

Hudson, New Hampshire

Dear Friends and Family,

This morning as I was reading through my Facebook feed I came across a link about one of my favourite authors: C. S. Lewis. So many things are written about Lewis daily that I don’t have time to read them all, so most of them I tend to skip. This one, however, caught my eye because of the title: The Shocking Beliefs of C. S. Lewis. The author, Frank Viola, was encouraged by a minister friend of his to point out to people the “shocking” beliefs of those they might hold in high esteem. The worthwhile point is not to downgrade these heroes in the eyes of others, but to show others that even those we account great have flaws and are, like us all, works in progress. I laud Viola for these worthy intentions, however, his selection of shocking beliefs were, to me at least, not shocking. Not only did they fail to shock me, but on most, if not all points, I agree with Lewis on these views. Furthermore, Viola casts these views in the light of things an evangelical might want to discredit all of Lewis’s work for, but shouldn’t. I want to write this response to Viola’s post to point out two things: the first is, as I have said, the unshocking nature of Lewis’s beliefs; the second, is to serve as a reminder that Lewis does not (rightly so, in my opinion) conform to many American, conservative, evangelical descriptions.

Purgatory

The first shocking belief Viola ascribes to Lewis is a belief in purgatory. Now, this may very well shock his protestant audiences, I concede. But it is not so shocking that someone steeped in the Tradition and history of the Church might agree with one of the teachings of that Church. Protestants, and even some Catholics, have a lot of misconceptions about what Purgatory is. Somehow, we’ve come to view as an antechamber to Hell, a place of retributive punishment for our sins. However, as both Lewis, Dante, and Tolkien conceive of Purgatory it is a place of purgation. True, in Dante’s Purgatory there is a continuation of the kinds of reversal punishments seen in Hell. That is, the proud are brought low by having large stones set on their shoulders, the sexually immoral, chasing after lust, are now set to run in circles, away from their desires. In Tolkien’s ‘Leaf By Niggle’, Niggle must work, and work hard. Even in Lewis’s The Great Divorce, there is pain for those who choose to remain in Heaven. However, for all, the goal is not punishment, or at least not retributive punishment, it is purgation, a burning away of our imperfections (like dross from silver). The Scriptures are replete with imagery that suggests we must be cleansed before we are fit for eternal life. This is why, for me, Lewis’s belief in Purgatory is unshocking.

Praying for the Dead

The next shocking belief is that Lewis believed we ought to pray for the dead. This again is rather unshocking. Again, the Scriptures make it clear that we ought to be mindful of the dead, there is even that enigmatic passage in Paul concerning being baptised for the dead. Hebrews reminds us that we are surrounded by the dead, that great cloud of witnesses. The early churches often met in cemeteries or catacombs and it wasn’t long after that they used to set up their altars above the bodies (or relics) of the martyrs and saints. We are, as one rather Goth church I once attended was called, a Church of the Living Dead and ought not only to be mindful of them but pray to God for them, just as we did in life.

Those in Hell Might Journey towards Heaven

This one, I will grant, will be very shocking for many. After all, the parable in Luke 16 suggests that there is an unbridgeable chasm between the abode of the righteous and the abode of the wicked (in death, anyway). Lewis was influenced on this point by George MacDonald who was, in turn, influenced by Origen (as well as Plato). The key here, however, is that this is through Christ. It is noteworthy, that the bus driver in The Great Divorce is Christ himself, the only one who could make himself small enough to enter Hell. However, this view becomes even less shocking when we realise that for many in the early and medieval Church, Christ, in his death, descended into Hell. Some will seek to counter this by noting that even in the Apostle’s Creed, the word used is Hades, a general word, they argue, for the abode of the dead. However, both Luke 16 and interpretation of this statement throughout the centuries are against this narrow understanding of Hades. There is, therefore, nowhere where Christ’s redeeming work is absent, whether this may continue after death or even after the return of Christ is not really for me to say. But I hope.

Christians Do Not Have to Be Teetotalers

Drunkenness is evil, no two ways about it, but abstinence for the sake of abstinence is not the solution (this goes, by the way, for sex as well). Rather, just as for sex there is an appropriate context, namely marriage, so too is there an appropriate place for alcohol, and even the early effects alcohol has on your brain and body before drunkenness occurs. The Scriptures are, it is true, replete with condemnations of overindulgence (of alcohol and other things), but they also contain many passages praising the benefits of it. Think of Paul’s exhortation to Timothy to take wine for his stomach problems. It should also be noted that Lewis was a smoker. He primarily smoked pipes and cigarettes, and thought tobacco (though not necessarily the additives put in cigarettes) was beneficial as well. Consider the works of J. R. R. Tolkien where nearly every good character smokes a pipe (Bilbo, all thirteen dwarves in The Hobbit, Gandalf, Sam, Merry, Pippin, Gimli, Aragorn). Even Trumpkin the dwarf smokes a pipe in Prince Caspian, as well as Mr Beaver in The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe. Not to mention that Mrs Beaver hands round a flask that likely contains either brandy or whiskey.

A High View of the Eucharist Is Valid

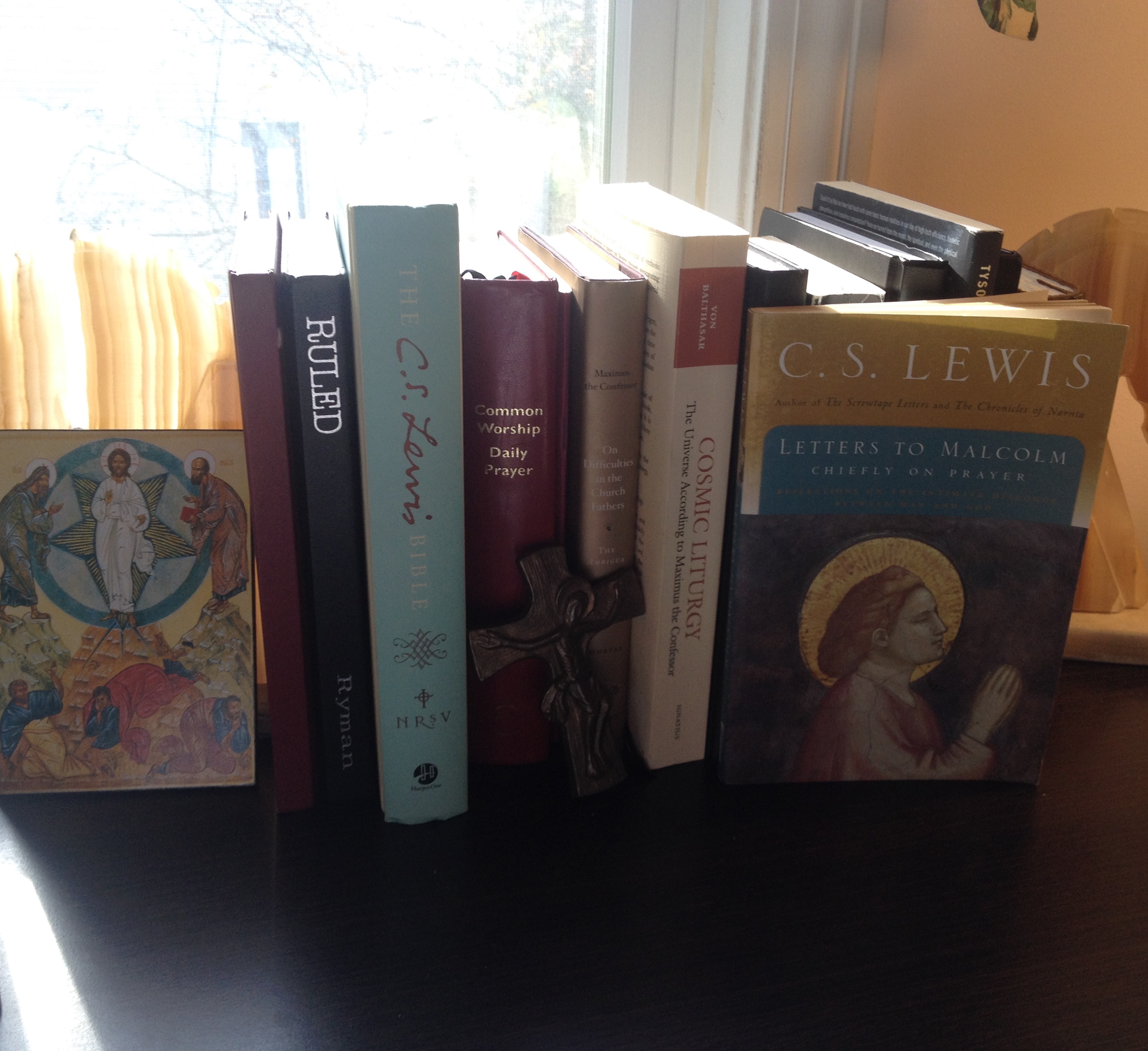

Viola frames this as Lewis saying that a Zwinglian (that is, purely symbolic remembrance) view of the Eucharist is just as valid as the Catholic View (of transubstantiation). Actually, he says the reverse, giving the priority to the Zwinglian view, and then he cites Letters to Malcolm. In fact, I agree, largely, with the Catholic view and think the Zwinglian view incorrect. Lewis is not so obvious. What he says, rather, is that both views are inconceivable, that is, he has trouble believing either of them. His emphasis of disbelief, however, resides more with the purely symbolic remembrance than it does with transubstantiation. Lewis wants to take seriously Christ’s words, this is my body, this is my blood. However, he ends, rather unshockingly, with this notion: the command is to take and eat, not take and understand (Letters to Malcolm Chapter 19). Whatever happens in the Eucharist transcends our knowledge of it.

It is also worth noting that Lewis, as a member of the Church of England, would have received the Eucharist in the form of wafers of bread and one large cup of wine shared by all. This is likely to shock many evangelicals who use small crackers or bits of pie crust and small cups of grape juice. Equally problematic would be that Lewis would have received these elements at the hands of another, not taken them from a passing tray. This should not shock, however, since the modern practice is an innovation, and certainly not how Christ and the Apostles would have celebrated this meal.

Job Is a Work of Fiction, and the Bible Has Errors

Viola gives little support to this, but simply recommends readers look at Lewis’s Reflections on the Psalms. He also misleads his readers a bit. While Lewis may well have thought Job to be fictional, it was a work of theological fiction and no less a part of the Scriptures because of it. Equally, while Lewis may have thought the Bible contained errors, these were not errors (I.e. He would not say the Bible is inerrant), this more has to do with occasional historical errors (who was king and for how long and after whom, etc.) and other small errors. This did not, however, mean that the Scriptures did not have one divine author as well as many human authors, or that the Scriptures are not God-breathed. Again, this is the position of much of the Church over history.

In the end, perhaps these facts are shocking to Evangelicals, but they shouldn’t be. Equally, these should not be little foibles Lewis had that ought to be criticised alongside the aspects of Lewis that ought to be lauded. Instead, we ought to consider how these supposedly “shocking” views informed and were informed by his “acceptable” views. Perhaps if we do that, we will see that we cannot have “Evangelical” Lewis without also having “Catholic” Lewis, that Catholic and Evangelical ought and do go together.

Sincerely yours,

David