The most magnificent charitable gesture can fall flat if it turns out that you just did it to get a promotion, or get some other kind of pay off. People don’t like it if they think they detect a hidden motive behind apparently charitable behaviour.

Last year, research by University of Kentucky psychologist Will Gervais showed that something similar seems to happen when people do charitable deeds motivated by their religious beliefs. Observers will rate them less favourably than if the same deeds are done for secular reasons.

The question is, is this something that linked to our beliefs about religious people, or about religious motives? And is it something that’s innate, or learned?

Larisa Heiphetz at Boston College in the USA, and colleagues ran a series of studies to learn more. And the results are really interesting.

They interviewed 269 kids between the ages of 5 and 10 and showed them PowerPoint displays about characters who did some simple altruistic acts, such as helping his or her friends to make an art project for school. Some characters, they were told, were motivated by religion (they did it “to make God happy”). Others had secular motives (to make his or her parents happy).

They were then asked about which characters’ behaviour was better. The answers they got depended on whether or not the kids had religious parents.

The answers they got depended on whether or not the kids had religious parents.

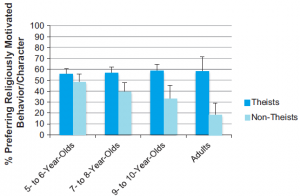

At all ages, kids of religious parents preferred the religiously-motivated characters. What’s more, when they tested religious adults they found a similar bias.

They got a different result with the children of non-religious parents. At young ages they preferred religiously motivated characters, just like the kids of religious parents. But as they got older that preference decreased – and non-religious adults were decidedly hostile to religious motives.

So it seems that non-religious people are learning as they develop to be sceptical of religious motives. The investigators did another couple of studies to find out why.

First off, it’s not to do with the fact that there are more religious people. They thought that young kids might prefer religious motives just because it seems more normal, more typical. But when they subtly tweaked their perception about the prevalence of religious people, it had no effect.

So then they looked at prejudice and thinking style.

They used something called the Implicit Association Test to reveal that, although both religious and non-religious adults are subconsciously prejudiced against non-believers, the effect was much stronger among the religious.

Then they measured teleology – the tendency to wrongly assign meaning and purpose to things that just happen to be associated (e.g “The sun shines because it helps the plants to grow”). They found that “The more likely participants were to intuitively perceive purpose-driven design in the world around them, the stronger were their pro-theist preferences.”

What this suggests is that there is an instinctive preference for religious motives, which non-believers consciously reject.

Here’s what they say about why teleological beliefs and preference for religious motives correlate:

One possibility is that the more individuals perceive aspects of the world as created for a purpose, the more drawn they may be to individuals whose motivations are in line with the belief that an intentional agent (i.e., God) could be responsible for such creation.

I suspect a simpler explanation. We know that instinctive thinkers are more likely to believe in a personal god, that Hare Krishna worshippers are also instinctive thinkers, that paranormal believers are confused about how the world works, and that deep thinkers are more likely to lose their faith.

All of which suggests that people who are able to overcome their instinctive beliefs and adopt a more considered world view are more likely to lose their faith. It would not be surprising, therefore, if they were also more able to overcome an instinctive preference for religious motivations.

![]() Gervais, W. (2014). Good for God? Religious motivation reduces perceived responsibility for and morality of good deeds. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 143 (4), 1616-1626 DOI: 10.1037/a0036678

Gervais, W. (2014). Good for God? Religious motivation reduces perceived responsibility for and morality of good deeds. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 143 (4), 1616-1626 DOI: 10.1037/a0036678

Heiphetz, L., Spelke, E., & Young, L. (2015). In the name of God: How children and adults judge agents who act for religious versus secular reasons Cognition, 144, 134-149 DOI: 10.1016/j.cognition.2015.07.017