Today is the Feast of the Ascension, when Christians remember how Jesus was taken up into heaven 40 days after his Resurrection. It’s one of the stranger bits in the Gospels — both difficult to fit into our modern cosmology, and difficult to pull off visually — and most of what we know about it actually comes from the Book of Acts. So most films about Jesus have tended to skip this episode.

Today is the Feast of the Ascension, when Christians remember how Jesus was taken up into heaven 40 days after his Resurrection. It’s one of the stranger bits in the Gospels — both difficult to fit into our modern cosmology, and difficult to pull off visually — and most of what we know about it actually comes from the Book of Acts. So most films about Jesus have tended to skip this episode.

Nevertheless, a few films have depicted the Ascension, often by mixing it with elements from other stories in the gospels; and even those that don’t depict the Ascension have often made a point of ending on a note that suggests Jesus has transcended this life in some way that parallels the Ascension. Here are a few examples.

First, let’s look at films that depict the Ascension directly.

One of the earliest examples is in the silent film The Life and Passion of Jesus Christ (1902-1905). Because this film is so stylized — it’s basically a series of icons that move — it doesn’t have to worry about how “realistic” its depiction of the Ascension is, or even how good its special effects are. Instead, it shows Jesus standing on a slightly rickety platform of sorts that is raised and drawn towards the back of the stage…

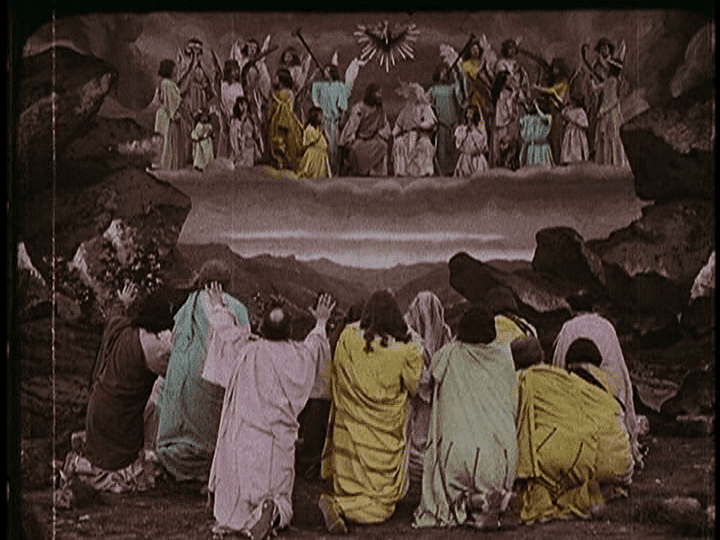

…and then the film dissolves seamlessly so that Jesus is now surrounded by angels, as he sits down at the right hand of the Father under a symbol of the Holy Spirit:

Interestingly, while the Book of Acts tells us that Jesus disappeared behind a cloud, this film uses cloud-like shapes to hide the ropes that are lifting the platform on which he stands, and Jesus himself apparently remains visible to the disciples throughout this scene — and the rest of the heavenly court is visible to them too!

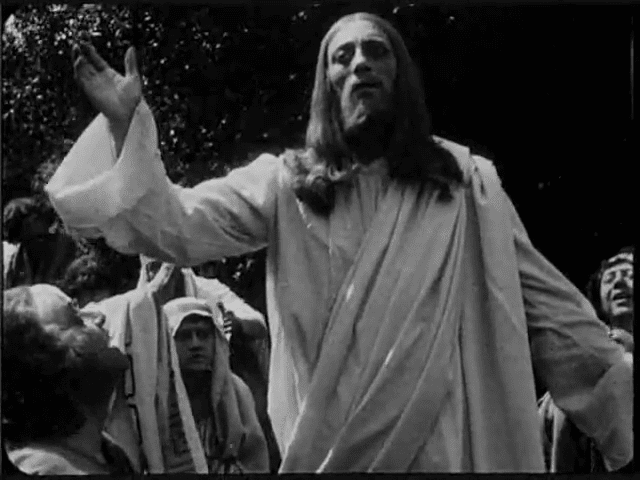

Another silent film that depicts the Ascension is the Italian film Christus (1916), and what’s interesting about this depiction is that the film as a whole tends to be more naturalistic — outdoors scenes are actually filmed outdoors, and not on a stage that is dressed to resemble the outdoors — but it also ends on a very iconic note.

Note how the Ascension itself begins during a medium shot in which we see Jesus in the company of his disciples, and he begins to rise above them:

The film goes on to show Jesus from even wider shots, which it intercuts with images of the disciples watching him and raising their hands in awe. The first wider shot shows that Jesus’ feet are no longer on the ground:

An even wider shot shows him flying through the air:

And finally, just before the film ends (at least in the version I found on YouTube), Jesus does not disappear behind a cloud but, instead, is drawn into a heavenly circle:

Incidentally, this final image is preceded by a quote from Dante’s Divine Comedy…

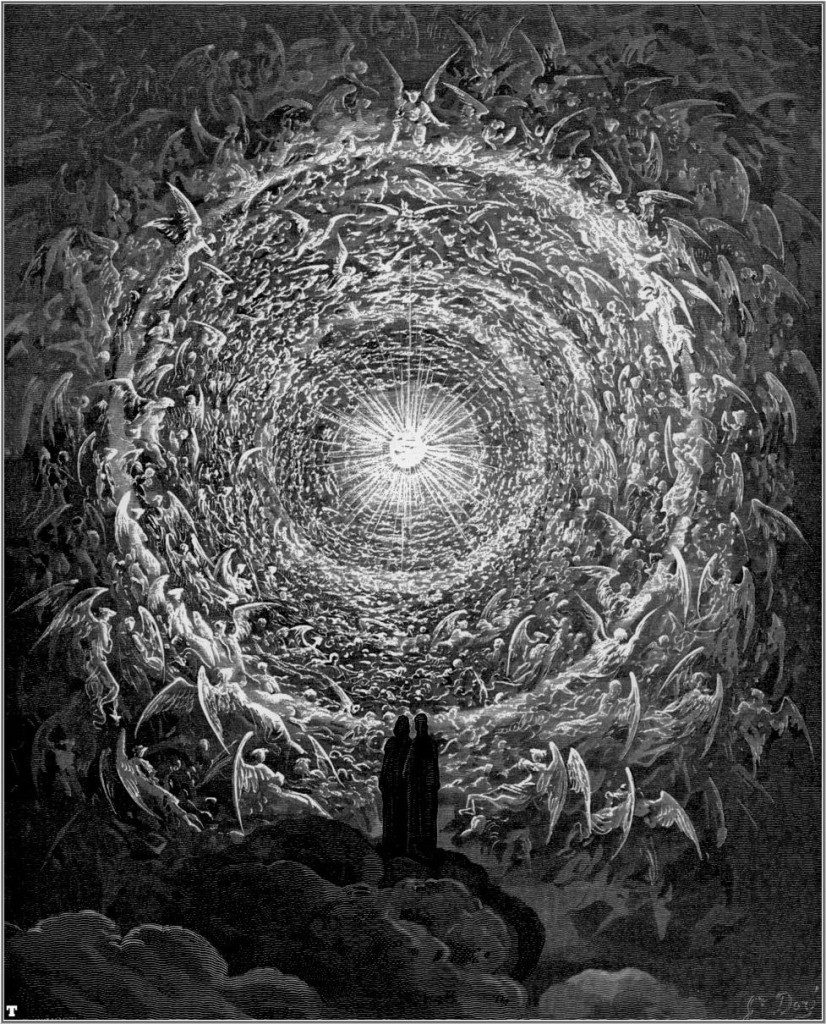

…which leads me to think that the film’s image of Heaven was inspired by this etching that Gustave Doré did for an edition of Dante’s work:

Among Hollywood films, the only clear depiction of the Ascension that resembles what we find in Luke-Acts comes at the end of The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965) — but here, the film breaks things up, so that we never see Jesus and the disciples in the same shot. Instead, an image of the disciples obscured by fog is joined in a slow dissolve by an image of Jesus, who already seems to be floating through the clouds:

Unlike the silent films, this one has Jesus speak while he ascends — and the benediction he gives is an odd mish-mash of his final words from Matthew and Acts as well as some random teachings from the Sermon on the Mount (“Leave tomorrow to fret over its own needs,” etc.). Then it dissolves to a shot of the sky…

…and then it dissolves to the ceiling of a church, where we find an icon of Jesus that looks just like Max von Sydow, the actor who played him in this film:

There’s an ongoing tension between symbolic and representational art in Jesus films, and few things bring it out like the Ascension. This tension is also present, I would argue, in the fact that the icon at the end of this film looks just like the actor.

One of the more unusual Ascension scenes takes place in Dayasagar (1978), a Jesus film made in India. In this one, the disciples don’t look up simply because Jesus is rising into the sky, but because Jesus seems to be growing much, much bigger.

Here is a point-of-view shot of Jesus, as seen by the disciples:

And here is a wider shot:

Eventually Jesus fades from the picture, leaving the stars behind in the background:

I don’t know what sort of resonance the image of a “colossal” Jesus would have for an audience well-versed in Hindu mythology. But in an essay on Jesus films made by foreigners and minorities, published in Son of Man: An African Jesus, Darren Middleton and S. Brent Plate note that Jesus’ robes in this scene form a diamond that resembles the geographic outline of India, as embodied in iconic images of Bharata Mata (‘Mother India’). Thus, the Jesus of this film is a Jesus that Indians can identify with.

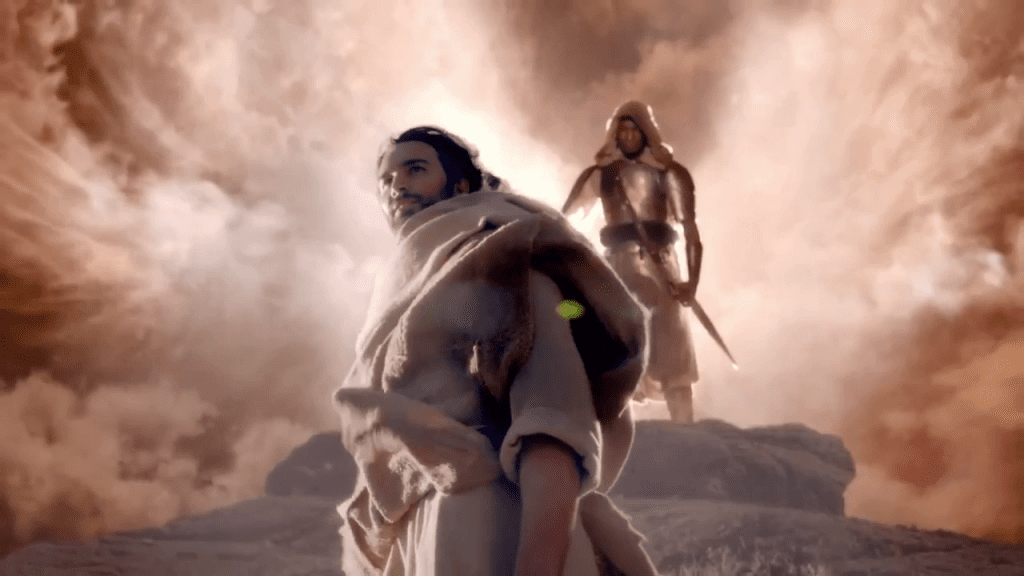

One year later, Campus Crusade co-produced the Jesus film (1979), and since it is based almost entirely on Luke — the only gospel that actually mentions the Ascension — you might expect it to depict the Ascension. And sure enough, it does, but indirectly.

First we see the disciples kneel as an offscreen Jesus addresses them (using dialogue from Matthew’s gospel, rather than Luke’s!). Then a wind begins to whip through their hair and robes, almost as though Jesus were being lifted up by a helicopter:

The Ascension itself is shown from Jesus’ point of view, looking down at the disciples:

And so, when the cloud appears (as per Acts; Luke’s gospel never mentions it), it does not hide Jesus from the disciples but, rather, it hides the disciples from Jesus!

Some years later, the Visual Bible produced a word-for-word adaptation of Acts (1994), so it too depicts the Ascension. Like Christus, it begins with medium shots of Jesus rising as he talks to the disciples outdoors (that’s James Brolin playing Peter)…

…before using a wider (and somewhat goofily executed) visual-effects shot of Jesus zooming away from the camera into the blue sky…

…and then, finally, he sort of disappears behind a cloud, though the cloud itself is so wispy that you almost think he must really be disappearing into a hole in the sky:

The animated film The Miracle Maker (2000) also has an Ascension scene of sorts, but it uses a subtler sort of visual effect. As Jesus speaks to his disciples, he walks among them, until suddenly he passes behind one of them and… disappears. Here you can see him about to walk behind the disciple in question:

And here you can see the back of his head after he has begun to walk behind the disciple in question:

And then, as the camera keeps tracking to the right, Jesus is gone; we do not see him walk out from behind the other side of that disciple:

Then, for the very last part of Jesus’ benediction, we see this close-up of Jesus talking to the camera — but where he is, and who he is speaking to, is never specified:

And then the film fades to white, and when it fades back to the disciples, Jesus is clearly no longer with them:

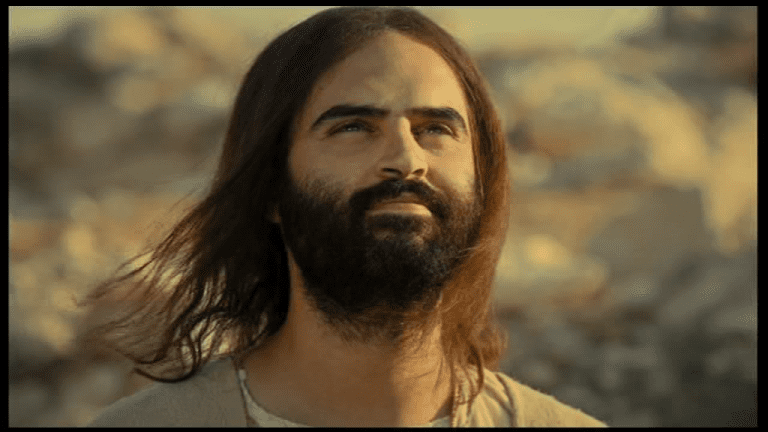

A similar, and even simpler, fade-to-white effect was used in last year’s TV mini-series The Bible (and its big-screen counterpart Son of God). Here, after Jesus gives the disciples his parting words, all we see is a simple close-up of Jesus’ face as the camera tilts back to reveal clouds parting and rays of light shining down from the sky…

…and then it fades to white. And then it fades back to the disciples.

And that about covers it for films that make some effort to depict the Ascension as it is described in the Bible. But there are other films that at least hint at the Ascension or find ways to suggest it or maybe even go beyond it.

Cecil B. DeMille’s The King of Kings (1927), for example, seems to end where a number of Jesus films do — with Jesus meeting his disciples in the upper room — but then, as the camera comes in on Jesus, the film replaces the disciples with a modern urban skyline, to suggest that Jesus is still with us today:

Then Jesus fades from the picture, and we are left with the cityscape:

Similarly, Day of Triumph (1953) ends with Jesus in the upper room but dissolves to an image of the rising sun, and as the two images overlap, it almost looks like Jesus has risen off the ground while the disciples are still kneeling on it:

Also, I can’t resist noting here that the image of Jesus growing in size, as he does in Dayasagar, actually has a sort of Hollywood counterpart in Nicholas Ray’s King of Kings (1961). This film does not end with the Ascension outside Jerusalem, as per Luke-Acts; instead it ends with Jesus meeting the disciples in Galilee as per Matthew and John. But instead of showing Jesus himself, what it shows is the disciples responding to Jesus’ voice by walking away from their fishing net, which they have put on the ground in a straight line — and then the shadow of Jesus rises from the lower left corner of the frame to intersect with the net, thus forming the shape of a cross. Look at how much bigger than the disciples’ shadows the shadow of Jesus is:

A few films, such as A.D. Anno Domini (1985) and Jesus (1999), have taken dialogue from the final verses of Matthew and Luke and used it in scenes where Jesus vanishes from the upper room, but I wouldn’t call those “ascension scenes” per se.

And then there is the interesting case of The Last Temptation of Christ (1988), which never even gets as far as the Resurrection — it ends, like From the Manger to the Cross (1912) and Intolerance (1916), with Jesus dead on the cross — but at the moment of his death, a light show begins that seems to suggest the film has jumped off its sprocket holes, and that surely suggests some sort of transcendence.

And that’s about it. A few points in closing:

First, it’s very common for people to assume that the final verses of Matthew (which give us the Great Commission) and the final verses of Luke (which describe the Ascension) are referring to the same event, and most films have combined these passages in some way. As noted above, even Campus Crusade’s Jesus film, which is supposed to be based on Luke only, has Jesus speak the words from Matthew!

But within a strictly literal reading of the gospels, the two passages simply cannot be conflated like that: the Matthew passage takes place on a mountain in Galilee, while the Luke passage takes place a short distance from Jerusalem in “the vicinity of Bethany”. Acts is even more specific, and places the Ascension at the Mount of Olives, “a Sabbath day’s walk” — or about one kilometre — from Jerusalem.

So what many of these films have done is engage in a bit of creative restructuring of the narrative — and one can certainly ask to what degree the authors of the gospels might have done something similar. Did they see what they were doing as fact-checked journalism, or did they see it as a kind of storytelling, akin to what the makers of these films have done? Would that sort of distinction have even made sense to them?

Second, the Ascension raises a number of cosmological questions.

For example, what does it mean to say that Jesus was “taken up” when the surface of the Earth points in all directions and there is ultimately no “up” or “down”? And why would he go up physically when Heaven, as far as we can tell, is not a physical location within this universe (and if it were, it is certainly nowhere close to this planet)?

For that matter, given how Jesus appears and disappears in the Resurrection accounts — and given how two angels appeared to the disciples “suddenly” right after the Ascension — why would Jesus need to travel through the air at all? Why couldn’t he simply disappear from the Earth and then appear, so to speak, in Heaven?

Questions like these bring to mind a famous line of Carl Sagan’s, to the effect that, if Jesus ascended at the speed of light (and the story in Luke-Acts suggests he didn’t), he would still be within our galaxy. So far, to my knowledge, no film has ever shown Jesus ascending into space, per se — though Christus comes pretty close.

(Similar questions could be raised in connection with films like Noah, in which some angels fall to Earth and we see them fall from outer space. Where did those angels begin their journey? How far out in space is Heaven supposed to be? Etc.)

Third, it is interesting to see how different films have wrestled with the question of literal versus symbolic representations of the Ascension.

Simply showing Jesus rise through the air, as in Acts, tends to look laughable if it isn’t handled with some artistic finesse (a la the theatrical iconography of The Life and Passion of Jesus Christ). Thus, a number of films have left the actual ascent of Jesus to our imaginations, either by keeping it offscreen a la the Jesus film, or by fading to white a la The Bible. Other films, like The Greatest Story Ever Told and even The Miracle Maker, have kept Jesus visually separate from the disciples and have had him speak to the audience directly, so that what matters is not how it “really” happened but that we respond to the film the way we might to any other icon of Jesus.

It is also interesting to see how some films have made Jesus look very large during the Ascension or in similar scenes, to suggest his divinity or omnipresence. This is most explicit in Dayasagar, but the silent King of Kings and The Greatest Story Ever Told also use overlapping images to make Jesus seem much bigger than his disciples or bigger than entire cities — not in a literalistic sense, but in the sense that he dominates the visual space. And of course there is that shadow in the other King of Kings.

So, that about covers it. If I’ve left any films out, please let me know in the comments.

May 14, 2015 update: Here are two more films to consider.

First, the Arabic film The Savior (2013) shows Jesus walking with his disciples to the top of a hill, after which he recites some words from Matthew and Acts.

Then, after Jesus has finished giving his benediction, he looks into the sky…

…as a beam of light comes down and envelopes him before rising back into the air:

The shots with the light beam are intercut with shots of the apostles covering their eyes and looking at it. But the main thing to notice here is how the film modifies the text by having Jesus disappear behind something — a beam of light, in this case, rather than a cloud — before he ascends, rather than afterwards.

And then there is this year’s TV series A.D. The Bible Continues (2015).

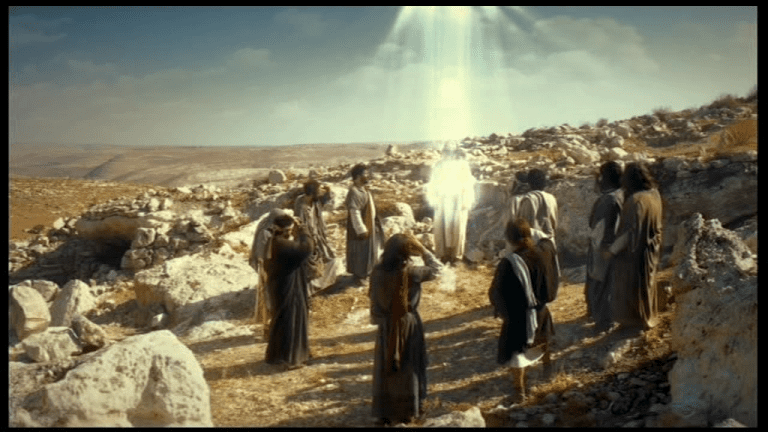

In A.D., unlike the book of Acts, Jesus does not rise into the sky and disappear behind a cloud. Instead, he walks up a mountain as a cloud seemingly comes down to Earth, and within that cloud there are dozens of angels, seen from a variety of angles:

Producer Mark Burnett has said the angels were put in this sequence to foreshadow the Second Coming, when Jesus will return with his army of angels.

The only other films I can think of that have shown angels in the heavens as part of their Ascension sequences are the two silent films at the top of this post: The Life and Passion of Jesus Christ and Christus. So in a strange way, A.D., for all its newfangled visual effects, actually harks back to a much older kind of pious spectacle.

And yet, unlike those silent films, A.D. does not show Jesus lift off the ground. Once again, it seems the filmmakers who tackled this sequence couldn’t find a way to make a literalistic depiction of the Ascension “work”, so they hinted at it instead.

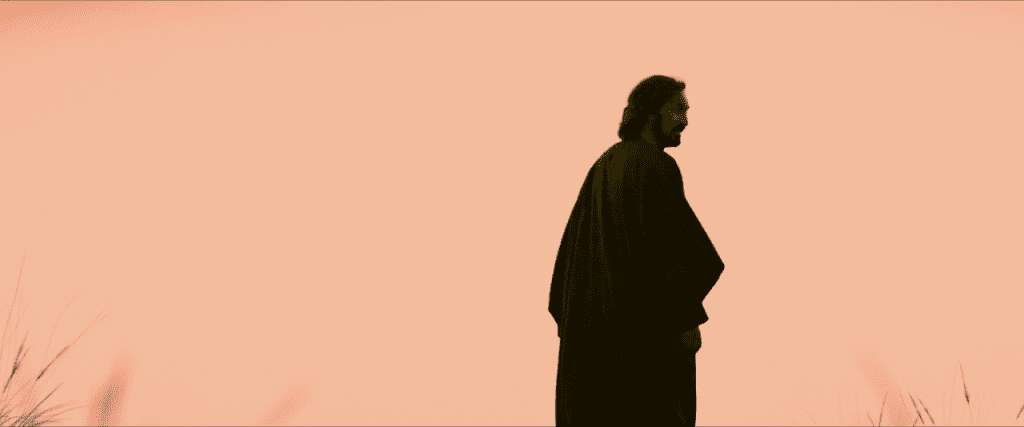

May 10, 2016 update: The Ascension is also featured in Risen (2016), which came out on Digital HD today. In it, Clavius and the disciples look to the horizon…

…and see Jesus standing there:

Jesus starts walking backwards — speaking a pastiche of sayings from Matthew, Mark, John and Acts — and then he turns to face the rising sun as he walks towards it, though he still looks over his shoulder to speak to the disciples:

Finally, he turns around to face the disciples again, and waves farewell:

He is obscured by the light of the rising sun…

…and then the camera pans up as a surge of light heads towards the sky:

Clavius and the disciples turn away from the gust of light and wind:

When the wind dies down, Peter and the others look at where Jesus used to be…

…and there is now only the risen sun:

Note: Risen, like A.D. The Bible Continues, places the Ascension in Galilee, and not in Judea. Like many other films, it fuses the Ascension with the Great Commission.