The Twelve Days of Christmas are over, not just because your true love gave to you twelve drummers drumming but because today is Epiphany. On this day, we commemorate the wise men’s homage to the Christ child and thus His revelation to the Gentiles, ushering in a whole season of revelations (a.k.a., “epiphanies”) of Christ (His baptism, His first miracle, etc.), culminating in His Transfiguration. After that high point, we descend with Christ into Lent.

Today we consider Jimmy Carter’s genuine accomplishments; independence for Greenland; and indulgences for the Jubilee Year.

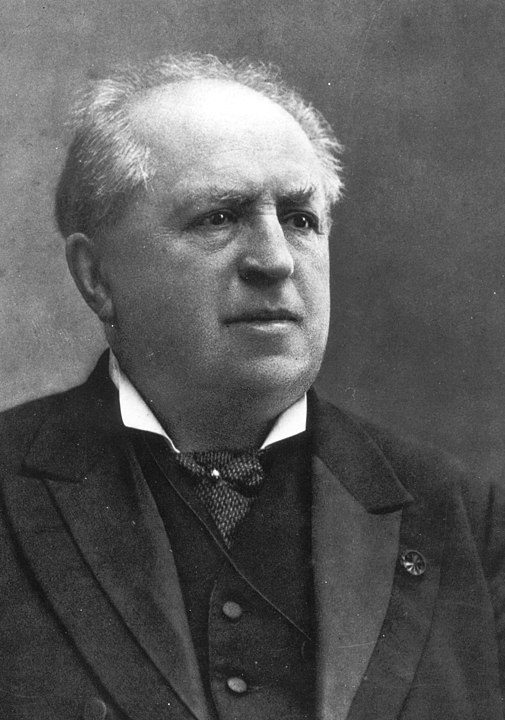

Jimmy Carter was 100 years old when he died on December 29.

The first time I was old enough to vote in a presidential election, I cast my ballot for George McGovern, liberal that I was then back in 1972. By the next presidential election in 1976, I was an evangelical Christian, though not yet a Lutheran, so I voted for Jimmy Carter, thinking naively that his open evangelicalism would make him a better president than Gerald Ford.

Carter’s was not a successful presidency. After he was defeated for a second term by Ronald Reagan, Carter devoted himself to good works, such as building houses for the poor through Habitats for Humanity and negotiating peace treaties as if he were still president, earning a Nobel Peace Prize though not always supporting the right people and drifting ever further to the left. For his weaknesses as a president and afterwards, see this.

And yet, his legacy included some genuine accomplishments that we still benefit from today, as Dominic Pino reminds us in his article Progressives Hate Jimmy Carter’s Best Accomplishments.

Carter deregulated the airlines. Before that, the Civil Aeronautics Board determined the routes that airlines could fly, kept the airlines from competing with each other, and set the prices they could charge. Carter dissolved the Civil Aeronautics Board, showing that it’s possible to actually eliminate a federal agency! Airlines started competing with each other, dropping prices and adding routes, making air travel accessible for ordinary Americans. In the 1970s, before regulation, 49% of Americans had flown on an airline. By 2020, that number had risen to 87%.

Carter deregulated the trucking industry. Before that, the Interstate Commerce Commission decided which routes the trucking companies were allowed to operate and how much they could charge. Deregulation unleashed competition, which sped deliveries and dropped prices. It also opened the door for thousands of independent owner-operators, creating good jobs and improving service even more.

Carter deregulated the railroads. Before that, the Interstate Commerce Commission set routes and prices. The freight train industry was becoming like AmTrak, being forced to operate unprofitable routes by federal regulations. Again, deregulation brought down prices and improved service. Shippers saved billions, delivery times dropped, and today the U.S. has the largest freight-rail network in the world.

So if you or someone in your family flew somewhere for the holidays or bought gifts online with two-day delivery, thank Jimmy Carter.

And DOGE Committee and President Trump, take notice.

Independence for Greenland

President-elect Trump has been talking about buying Greenland from Denmark, yanking the chains of Europeans and stirring fears among progressives of American “expansionism” and “colonialism.”

Greenland, at 836,330 sq. miles, is the size of Alaska and Texas combined and its area is over a fifth, 22%, of the size of the entire United States. Its natural resources are vast and mostly untapped, and its strategic importance in the arctic–an area both Russia and China are contending for–is critical. And yet, because 85% of Greenland is under ice, it has a population of only 57,000.

Denmark says it won’t even consider selling its territory and has and the residents insist they are not for sale.

But the kerfuffle has stirred Greenlanders into considering an alternative: seeking independence from Denmark and making Greenland a sovereign nation.

In his New Year’s speech, the prime minister of Greenland Mute Egede said, “It is about time that we ourselves take a step and shape our future, also with regard to who we will cooperate closely with, and who our trading partners will be.”

There is a big reason why Greenlanders are resenting Danish rule. In 2022, a podcast uncovered shocking information. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, Denmark was imposing involuntary birth control on Greenland’s population. Danish doctors implanted IUDs in young Inuit women and girls as young as 12 without their consent or knowledge. This was part of an intentional policy to stop the territory’s population growth. The devices, which work by preventing fertilized embryos from implanting and are thus abortifacients, often created complications including sterility.

A 2022 story on the findings shows the outrage felt by Greenlanders:

Reactions to the podcast have been harsh. “The case is completely absurd and should in no way be ignored or camouflaged. Call it what it is: Genocide”, Greenlandic MP in Denmark Aki-Matilda Høegh-Dam said to the Greenlandic news website sermitsiaq.AG. She argues that the IUD campaign falls under the UN definition of genocide for the crime of “imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group”. Greenlandic MP Doris J. Jensen said that the disclosures are of such severity that the relationship between Denmark and Greenland should be reconsidered, thereby suggesting a future Greenlandic declaration of independence.

Denmark is conducting an investigation, with the report scheduled to be released this year. That report could be explosive.

Because of its own history, the United States should support independent movements out of principle. The pro-life issues should make American Christians especially sympathetic to Greenland.

Because of our history and that principle of independence, the United States should never take over another country or its territories without consent, which would place us in the same role as the foreign powers we rebelled against.

As far as American interests, though, an independent Greenland could fulfill what Trump called the “absolute necessity” of the U.S. having that vast island. That Prime Minister Egede wants Greenlanders themselves to determine “who we will cooperate closely with, and who our trading partners will be” suggests dissatisfaction with the decisions that Denmark has been making for them.

Surely the United States would be a more formidable protector against Russia and China than the Danes would be. And as a trading partner, the United States would surely bring more prosperity to Greenlanders than the Danes have done. An independent Greenland could be brought into the American orbit, to the benefit of both.

Indulgences for the Jubilee Year

For the Roman Catholic Church, 2025 is a “Jubilee Year.” This is not the same as the ancient Hebrews’ Jubilee described in Leviticus 25, the year after “seven weeks of years” in which debts were forgiven and ancestral property was returned to its original owners. Instead of being every 50 years, the Catholic version comes up every 25 years. Instead of the debts forgiven being monetary, the debts forgiven are the temporal penalty due for sins that have been absolved and forgiven by God, but which still must be punished, if not on earth in Purgatory. The way that happens is by receiving indulgences.

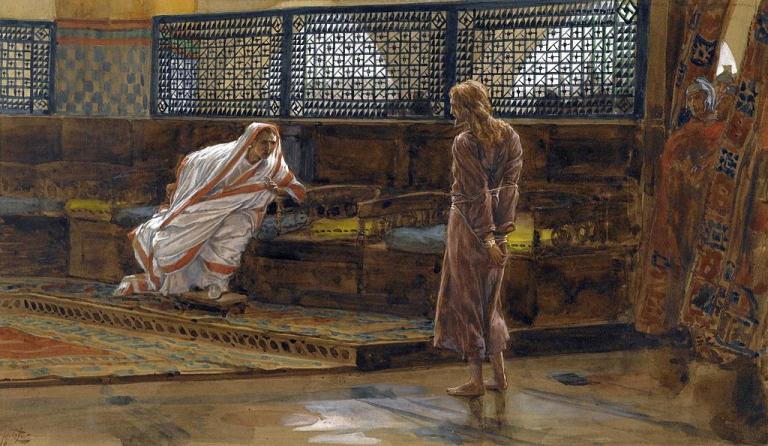

Luther’s critique of the sale of indulgences did have an effect on the Roman church. Indulgences are no longer sold for money. But Catholics still believe that indulgences can lessen or even eliminate the time a soul must spend in Purgatory. Christians can earn indulgences as bestowed by the church by performing various acts of devotion. In a Jubilee Year, extra opportunities to earn indulgences are made available, particularly by means of pilgrimages.

Courtney Mares helpfully explains in an article for the Catholic News Agency entitled How to Obtain a Plenary Indulgence During the 2025 Jubilee:

A plenary indulgence is a grace granted by the Catholic Church through the merits of Jesus Christ to remove the temporal punishment due to sin.

The indulgence applies to sins already forgiven. A plenary indulgence cleanses the soul as if the person had just been baptized. Plenary indulgences obtained during the Jubilee Year can also be applied to souls in purgatory with the possibility of obtaining two plenary indulgences for the deceased in one day, according to the Apostolic Penitentiary.

You can get a plenary indulgence–that is, a complete cancellation of punishment for all your sins up to that time–by walking through the “Holy Doors” of one of the four Basilicas in Rome. Another set of Holy Doors will be set up in an Italian prison

You can also get a plenary indulgence by making a pilgrimage to one of the churches in Rome named after a female saint.

If you can’t afford to go to Italy, you can also get indulgences by going to a local cathedral, performing “works of mercy” (“visiting prisoners, spending time with lonely elderly people, aiding the sick or disabled, and helping those who are in need”), or other specific actions (such as “Abstaining for at least one day a week from ‘futile distractions,’ such as social media or television”).

Read the article for details and for other means of avoid punishment for the sins that God has forgiven. The author says that for these indulgences to work, they must be accompanied by “Sacramental confession, holy Communion, and prayer for the intentions of the pope.”

It has always puzzled me that while Catholics do believe that Jesus has atoned for our sins and forgives them, that forgiveness only means we will not be damned for them. We are forgiven, and yet we still must be punished. And yet, the church, through the authority of the Pope, can remit that punishment. This happens because the Pope can apply the “treasury of the saints,” the extra the saints accumulated that are more than they need for their salvation, to our account. So why can’t the infinite merit of Christ be applied to our accounts? Why doesn’t the punishment of Christ in our place eliminate the need for our punishment?

The church still needs Luther.