We’ve been worrying about politics and sorting through political theories. But Advent is a good time to remember that ultimately none of that matters. The true King has come and is coming again.

The word “advent” is Latin for “come to.” Jesus has not only come, He has “come to” us. He is not only coming again, He is “coming to” us. On that little preposition hangs the Gospel. Yes, He comes to be our judge, as the Te Deum praises, but His coming above all is to us and for us, so as to save us.

In Advent, we meditate on Christ’s coming as celebrated in Christmas, reflecting on the Old Testament prophecies of the Messiah. We also meditate on Christ’s second coming, which we await in hope, just as the Old Testament saints awaited His first coming.

So we pray, “Come, Lord Jesus!” That prayer is the next to the last verse of the Bible (Revelation 22:20), going from the apocalyptic account of what that will be like and what it will mean to the prayer of the church until that happens. It was indeed the prayer of the earliest church as evidenced in St. Paul’s interjection into his Greek epistle of a word in Aramaic, the language of Jesus: Maranatha, which can mean either “O Lord, come!” or “the Lord has come”–both of the senses of Advent.

“Come, Lord Jesus” is echoed in the Common Table Prayer beloved by Lutherans (“Come, Lord Jesus, be our guest/And let these gifts to us be blessed”) which seems like a simple children’s prayer, but is much more, asking for Christ’s presence–a pervasive theme of Lutheran theology–with the family at mealtime, alluding to the teaching that Christ is present in vocation as we love and serve and provide for each other.

At any rate, “Come, Lord Jesus” is the ultimate Advent prayer. Notice how often we pray that phrase in our Advent hymns; for example, “”Savior of the Nations, Come” and “O Come, O Come, Emmanuel.”

Philip Jenkins reminds us of an ancient variation, found in the Didache (c.100AD): “Maranatha! Come Lord Jesus. And let the present world pass away!”

Yes, let it! That is an important aspect of Christ’s return! With His second coming, “the former things”–the kingdoms of this world, the first heaven, the first earth, death, mourning, pain–“have passed away” (Revelation 21:1-4).

Living in anticipation of that passing away means that we do not have to be preoccupied with such things, since we know that they will not last and that something better awaits us, either when Christ comes again or when we leave them behind when we die.

But isn’t our life on earth important? Isn’t focusing on the other world a form of spiritual escapism? Aren’t we responsible to obey God by fighting evils and making this world a better place?

Of course, but I think that the perspective that comes from knowing that this world and its kingdoms will pass away and that Christ will “make all things new” (Revelations 21:5) can make us more effective in this world. As C. S. Lewis said in Mere Christianity, “If you read history you will find that the Christians who did most for the present world were just those who thought most of the next.”

This is because their hope never fails, despite the setbacks they may encounter, and because they can be confident of the ultimate victory of righteousness in Christ’s judgment. They can act freely, without feeling the burden that everything rests on themselves. And they can act without succumbing to the temptations of power and the disappointments of failed utopias, since they realize their own limitations and the limitations of human ideologies. Such a mindset can help us as we fulfill all of our vocational duties, including our duties of citizenship.

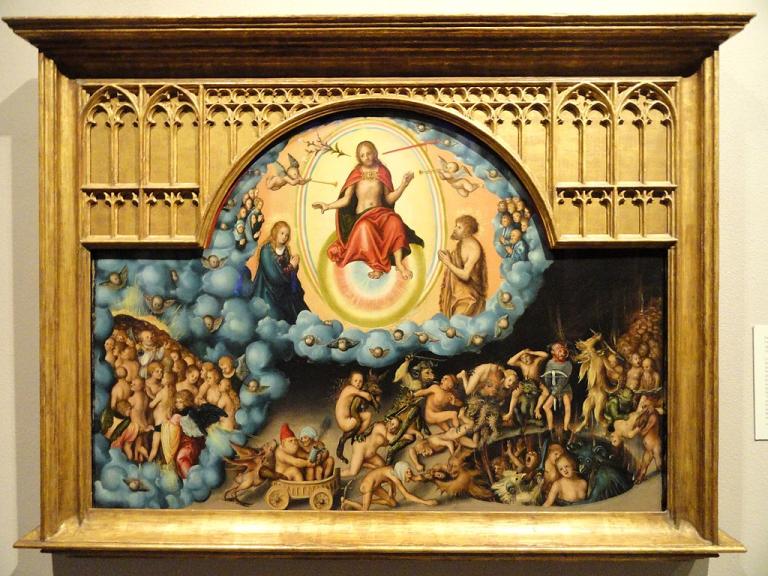

Illustration: “The Last Judgment” by Lucas Cranach the Elder, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons