In more news about Christians being prosecuted in Finland for disapproving of homosexuality, the Rev. Dr. Juhana Pohjola, who will be tried for his part in the publication of a tract on Biblical sexuality, has been made a bishop.

On August 1, he became the bishop of the Evangelical Lutheran Mission Diocese of Finland (ELMDF), a church body that in 2019 entered into full altar and pulpit fellowship with the Lutheran Church Missouri Synod.

The latest Lutheran Witness has an excellent article on the subject by Kevin Ambrust, who goes into detail about the consecration, the Evangelical Lutheran Mission Diocese, and the controversy surrounding Bishop Pohjola.

The list of participants in the service shows that Bible-believing Lutherans can still be found throughout ostensibly secularist Scandinavia. Conservative bishops from Sweden, Norway, and Latvia were there in support of Bishop Pohjola, as were representatives from the LCMS, including president Matthew Harrison.

From Kevin Ambrust, ‘To live is Christ’: Pohjola consecrated as bishop of Finnish Lutheran Church in The Lutheran Witness:

Participating in the consecration were the Rev. Risto Soramies, bishop of the ELMDF since its inception as an independent organization in 2013; the Rev. Dr. Matti Väisänen, bishop from 2010 to 2013, when the ELMDF was a mission diocese; the Rev. Hanss Jensons, bishop of the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Latvia; the Rev. Bengt Ådahl, bishop of the Mission Province in Sweden; the Rev. Thor Henrik With, bishop of the Evangelical Lutheran Diocese in Norway; and the Rev. Dr. Matthew C. Harrison, president of The Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod (LCMS). Clergy from the International Lutheran Council (ILC), the ELMDF and the LCMS — including the Rev. Dr. Jonathan Shaw, director of LCMS Church Relations; the Rev. James Krikava, associate executive director of the LCMS Office of International Mission and director of the LCMS Eurasia region; and the Rev. Dr. Timothy Quill, general secretary of the ILC — also processed in support of the new bishop.

“We Christians confess Jesus and His redemptive words and deeds as our life and salvation. Corrupt culture calls us to reject this ‘little Word’ in favor of flashy signs and woke wisdom. The consecration of Rev. Pohjola as bishop of the ELMDF, the LCMS’ newest sister church, was a witness to that triumphant ‘little Word,’” said Shaw. “How heartening to join with the faithful who boldly confess Christ and His doctrine, despite the liberal Finnish state church having defrocked ELMDF clergy, seized church buildings and brought criminal charges against Bishop Pohjola for publishing a pamphlet on divinely ordered human sexuality. Other confessional Lutheran churches — small by the world’s standards — sent their bishops to participate. Bishop Ådahl put it succinctly: ‘We are not a small church among big churches. We are the church.’ As the Body of Christ, we together receive from the fullness of His grace.”

Lutheran Bishops?

You may be wondering, what’s this about Lutheran bishops? I’m Lutheran and I don’t have a bishop.

Well, some denominations define themselves not by their teaching, as such, but by their church government. For Congregationalists, the individual congregation makes all the decisions. Presbyterians are governed by elders (Greek: presbyters), which means pastors and lay leaders. Episcopalians are ruled by bishops. Roman Catholics are ruled by the Pope.

What makes a Lutheran is not any particular kind of church government but adherence to the doctrines set forth in the Scriptures as taught in the confessions of the Early Church and the Reformation collected in the Book of Concord. Thus, Lutherans can be found with a number of different ecclesiastical polities. We Missouri Synod Lutherans are mostly congregational.

Though the Reformation brought conflict with different jurisdictions, that didn’t happen in Scandinavia, where the existing churches as a whole embraced the Reformation whole. Thus, they kept their bishops. This meant too that they retained Apostolic Succession, with their bishops being able to trace their lineage all the way back to the first Apostles.

Lutherans as a whole don’t consider that to be important. To be “apostolic,” as the Creed describes the church, is to follow the teachings of the apostles that they wrote down in the inspired words of Scripture. And it isn’t so much bishops who are in a chain of laying on of hands as pastors, the pastoral office having been established by Christ and bishops simply being pastors who have been elected to a position of particular responsibility.

But Roman Catholics, the Orthodox, and the Anglicans do put major emphasis on the Apostolic Succession, to the point of insisting that “valid orders”–that is, legitimate pastors–are only those who have been ordained by bishops in the apostolic train.

Conversely, Roman Catholics, Orthodox, Anglicans, and liberal state church Scandinavian Lutherans do have to recognize pastors ordained by bishops in the Apostolic Succession.

So they have to reckon with Bishop Pohjola, even if he is put in prison, and they have to recognize at some level the validity of the Evangelical Lutheran Mission Diocese of Finland, as well as those of Sweden and Norway, because they are Dioceses with valid bishops. (Some of those conservative churches that broke away from the liberal state churches had their bishops and first pastors ordained by the recognized bishops from Africa or the Ingrian Lutherans of Russia.)

Why “Mission”?

You may also be wondering why these new Scandinavian Lutheran churches have “mission” in their names. This is something really distinct in these nations, as I explain in my post Scandinavia’s Two Tracks of Christianity.

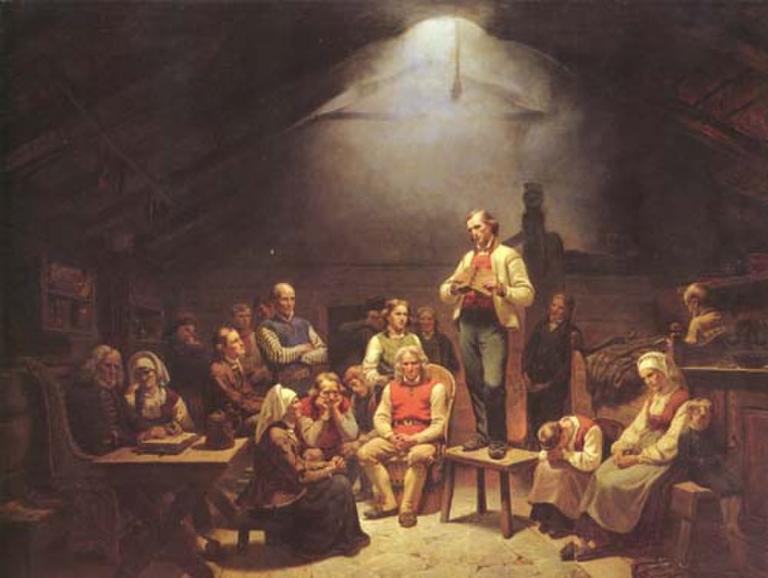

Briefly, the Pietist movement in the Nordic countries led to a proliferation of highly-evangelical groups known as Mission Societies. Pietism was often in conflict with Orthodox Lutheranism, especially in Germany, but in the Scandinavian countries, the state church made peace with these mostly lay-led groups, which began, with the church’s blessing, taking on aspects of the church’s ministry.

The Outer Mission groups sent missionaries throughout the world, and their highly-effective work is largely responsible for evangelizing–and planting thriving Lutheran churches–in many regions of Africa and Asia. The Inner Mission groups focused on ministry within the nations, organizing Bible studies, running Sunday Schools and youth ministries, caring for the poor, and operating a wide range of social ministries.

These Mission societies remain highly active today. And whereas the state church has gone extremely liberal, the Mission Societies are still theologically conservative and evangelical. Not only that, the Mission Societies, for all of their Pietist heritage, have become more and more Lutheran theologically.

Studies of religion in Scandinavia look at the empty state churches and conclude that Christianity is dead. But vital Christianity remains in the Mission Societies. Conservatives don’t attend the state churches anymore than the secularists do.

Things have gotten so bad with the established church that the Mission Society Christians are now getting together for worship. The parish churches meet on Sunday mornings, so the Mission services meet on Sunday afternoons. In Finland, they are not allowed to meet in church buildings, so they meet in school auditoriums and other locales. They conduct the Divine Service, including the Sacrament, presided over by ordained pastors who are sympathetic to the cause.

Some Mission folks have taken the next step: breaking away completely from the state church and forming their own church. To do this, they need their own bishops, who can ordain their own pastors. Thus we have the Evangelical Lutheran Mission Diocese of Finland, the Mission Province in Sweden, and the Evangelical Lutheran Diocese in Norway.

The situation in Denmark is different and better. According to Danish law, citizens have the right to form their own religious congregations. So Mission Christians are doing so, thus enabling a polity more like the Lutheran Church Missouri Synod. These Mission congregations can call their own pastors, who are being trained at the universities, where they have set up parallel theological institutes that conservative pastoral students attend.

As for Latvia, the Lutheran church in that Baltic Republic is the remnant of the state church that survived the persecution and co-option of the Soviet Union. Since then, the entire Latvian church has experienced a confessional revival–to the point of reversing its former practice of women’s ordination–and is now in altar and pulpit fellowship–that is to say, full doctrinal agreement– with the Lutheran Church Missouri Synod. Now the Latvian church is joining the International Lutheran Council, a global association of confessional Lutherans.

For more on all this, see my accounts of my visits to Finland and to Denmark and Norway.

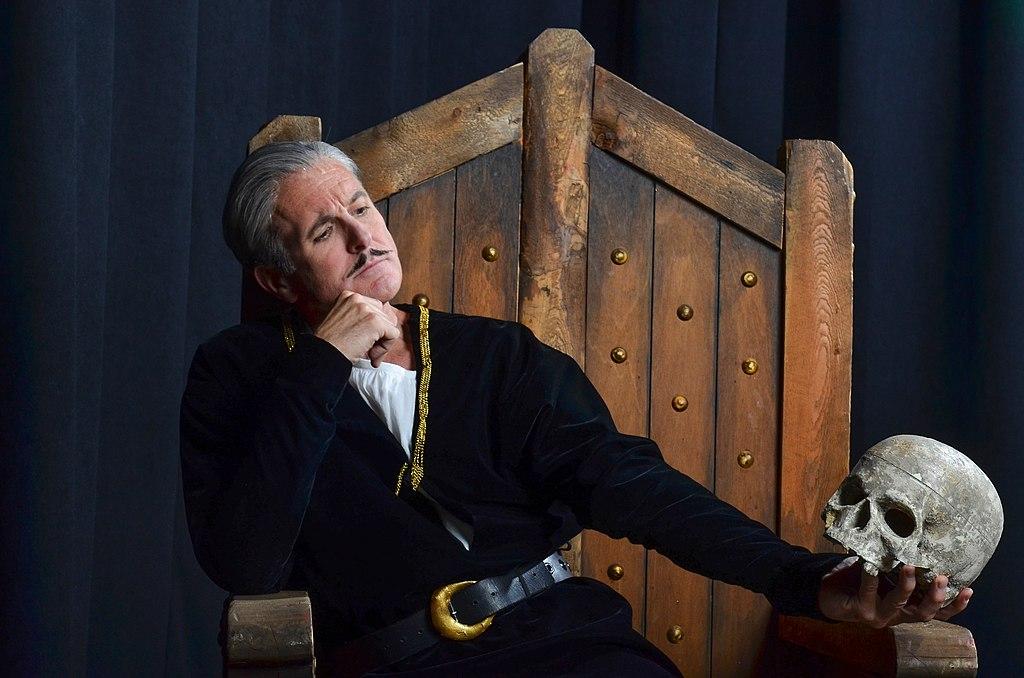

Photo: Bishop Pohjola, with attending bishops and clergy [LCMS president Matthew Harrison on right], via International Lutheran Council.