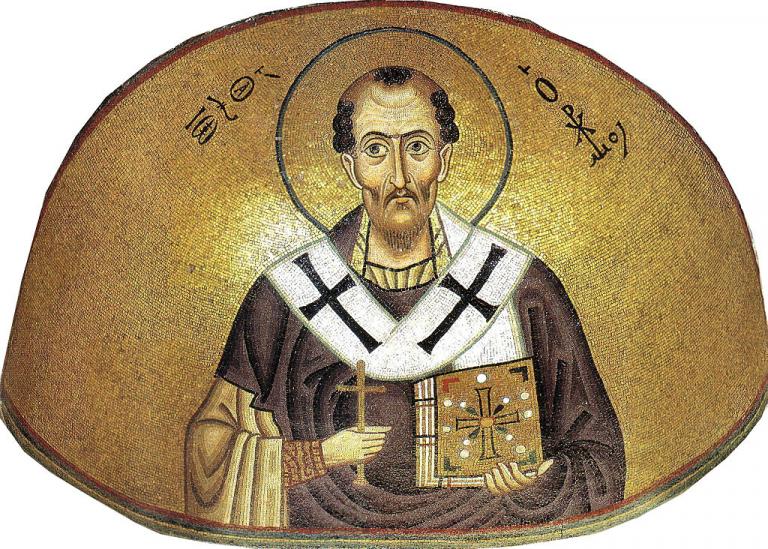

We Protestants don’t go by patron saints, but if there were to be a patron saint of literature, it should be St. John Chrysostom, that last name being an epithet for “golden-mouthed.” Now I know why.

In the reading group I attend with area pastors and teachers, we just finished Chrysostom’s On the Priesthood.

This is a classic of pastoral theology–useful for Protestant ministers as well as Catholic or Orthodox priests–that explores not only the theory but the practice of what the spiritual leaders of a congregation go through, showing that congregational dynamics (unrealistic and contradictory expectations, hurt feelings, and in-fighting) have not changed all that much in 1600 years.

But what struck me the most is the way it was written. It sets forth the value of the pastoral office by means of a dramatic dialogue arguing against becoming a pastor! Thus the arguments are all backwards and turned around, with abounding ironies and self-reflective contradictions.

The work was evidently written before John (349-407 A.D.) became “Chrysostom” or a saint or a leading theologian of Eastern Orthodoxy or the Bishop of Constantinople or even a priest. What this young Christian really wanted to do was be a monk–indeed, not being “sociable,” as he says, he wanted to be a hermit. But he promised his widowed mother, who could not bear to be parted from him, that he would not take that step until her death, so he took minor orders in the church at Antioch and became a “lector” who read the Scriptures during worship and who became something of an assistant to the Bishop.

He had a really close friend named Basil who likewise wanted to become a monk. They both heard from the grapevine that they had each been “elected” to be ordained as priests. At that time, in the early church, there were no seminaries or voluntary paths to the ministry. Churches just identified someone whom they wanted to serve as priest and elected him, whereupon he would be ordained.

But neither John nor Basil wanted to be priests. Nevertheless, the two agreed that they would both make the same decision on whether to be ordained or to refuse the honor. But while John felt unqualified and not up to the tasks, he believed that his friend would, in fact, make a good priest. So John got Basil to agree to through with it, but when the electors showed up, John went into hiding! Leaving Basil high and dry in the priesthood that he didn’t want!

The treatise On the Priesthood is a dialogue between John and Basil, who is furious with his friend for pulling this stunt. In defending himself, John explains why he turned down the priesthood but also why he wanted Basil to be one.

John has a high view of the pastoral office. It is better than being a king, he says. Kings preside over merely worldly matters, but pastors preside over spiritual matters. It is better than being an Old Testament prophet. Elijah called down fire from Heaven to consume the sacrifice and slay the idolaters, but preachers call down the Fire of the Holy Spirit on their hearers, bringing them into everlasting life. It’s just that John doesn’t feel worthy of holding an office so exalted.

John goes on to expound the heavy responsibilities of priests and all of the difficulties they have to deal with, from the logistical and personal difficulties of caring for the widows (we get a glimpse of the early church’s welfare system) to the misunderstandings and resentments that parishioners often fall into. (Our pastor shows favoritism! He is too harsh! He is too lenient! His sermons need to be more entertaining!)

He is haunted by this Scripture: “Obey your leaders and submit to them, for they are keeping watch over your souls, as those who will have to give an account. Let them do this with joy and not with groaning, for that would be of no advantage to you” (Hebrews 13:17). As a monk, he would only be responsible for his own spiritual state, which he thinks he could handle, but as a priest he would be responsible also for the spiritual state of others, and the prospect of that terrifies him. Because he would have “to give an account” before God. How could he endure that?

Basil keeps interrupting him with a plaintive “What about me?” If being a priest is so hard and potentially a danger to my soul, why did you stick me with it?

This is theology that you need to read like a novel, a literary form that would not be invented for 13 centuries, though Chrysostom might have invented it had he not succumbed to ordination a few years later. At one point in the dialogue, John says that anyone who desires to be a priest should not become one, since that would reveal bad motives. He then says that this is another reason he turned down becoming a priest, because he really would like to be one! So he doesn’t want to be a priest because he wants to be a priest. Which calls to mind an even bigger contradiction: If not wanting to be a priest is a qualification for becoming one, what do we make of his entire explanation why he doesn’t want to enter the priesthood? Doesn’t such unwillingness, in terms of his own argument, mean that he should become a priest? The multiple levels of ironic meanings outdo those of a postmodern novel.

Not that this is all just a rhetorical game. Chrysostom warns preachers against overdoing the rhetorical devices in sermons, insisting that Scriptural content is everything. There is nothing merely decorative or ornamental in Chrysostom’s writings. His literary genius shows up in the aptness of his expression, the vivid detail and effectiveness of his examples, and his mastery of language.

Protestants can’t go all the way with Chrysostom’s views–Holy Communion as sacrifice; no sense of the priesthood of all believers; his pervasive fear of falling short and being condemned to Hell–but there is much insight here. For example, I was struck by his point that priests and thus pastors must be “many-sided.” That is, they must be complicated. They will be dealing with many different kinds of people in many different professions and walks of life with many different kinds of problems. Their pastor needs to understand the people he is ministering to, which requires a wide range of interests and a multi-faceted sensibility. Notice how much good advice is packed into this one sentence:

For since he must mix with men who have wives, and who bring up children, who possess servants, and are surrounded with wealth, and fill public positions, and are persons of influence, he too should be a many-sided man — I say many-sided, not unreal, nor yet fawning and hypocritical, but full of much freedom and assurance, and knowing how to adapt himself profitably, where the circumstances of the case require it, and to be both kind and severe, for it is not possible to treat all those under one’s charge on one plan, since neither is it well for physicians to apply one course of treatment to all their sick, nor for a pilot to know but one way of contending with the winds.

He should be “full of much freedom.” He should be flexible, not applying the same medicine to every sickness. And, at the end, he finally answers Basil’s panic in terms of the actual solution: faith in Christ, the assurance of the Gospel, and vocation.

For I believe, said I, that through Christ who has called you, and set you over his own sheep, you will obtain such assurance from this ministry as to receive me also, if I am in danger at the last day, into your everlasting tabernacle.

He is asking Basil to be his pastor.

Two more things in conclusion. . . .On the Priesthood is available for free online, but I wanted to read it on my Kindle. Amazon makes available lots of classics that people aren’t reading much of anymore for ridiculously low prices, some of which cost nothing. One can download a Kindle edition of On the Priesthood for 99 cents. But then I saw that I could download The Complete Works of St. John Chrysostom for only $1.99. More works of Chrysostom, including hundreds of sermons, have survived than any other Church Father next to Augustine. So for two dollars I received 36 volumes consisting of 7,197 pages. That has to be one of the best bargains ever.

Finally, I give you one of his sermons. Chrysostom became famous for his preaching, which set aside much of the allegoricalizing approach to Scripture that was popular in his day in favor of a more literal exposition of God’s Word that was filled with perceptive insights and expressed with his “golden mouth.” (The Catholic Church did make him the patron saint of preachers.) This is an Easter sermon fitting for our season, since it will still be Easter until Pentecost. This sermon is read every year in Orthodox Churches. (Chrystostom is the author of the Orthodox liturgy for the Divine Service.)

From the Facebook page of the Lutheran Church Missouri Synod:

PASCHAL HOMILY OF ST. JOHN CHRYSOSTOM

Are there any who are devout lovers of God?

Let them enjoy this beautiful bright festival!

Are there any who are grateful servants?

Let them rejoice and enter into the joy of their Lord!

Are there any weary with fasting?

Let them now receive their wages!

If any have toiled from the first hour,

let them receive their due reward;

If any have come after the third hour,

let him with gratitude join in the Feast!

And he that arrived after the sixth hour,

let him not doubt; for he too shall sustain no loss.

And if any delayed until the ninth hour,

let him not hesitate; but let him come too.

And he who arrived only at the eleventh hour,

let him not be afraid by reason of his delay.

For the Lord is gracious and receives the last even as the first.

He gives rest to him that comes at the eleventh hour,

as well as to him that toiled from the first.

To this one He gives, and upon another He bestows.

He accepts the works as He greets the endeavor.

The deed He honors and the intention He commends.

Let us all enter into the joy of the Lord!

First and last alike receive your reward;

rich and poor, rejoice together!

Sober and slothful, celebrate the day!

You that have kept the fast, and you that have not,

rejoice today for the Table is richly laden!

Feast royally on it, the calf is a fatted one.

Let no one go away hungry. Partake, all, of the cup of faith.

Enjoy all the riches of His goodness!

Let no one grieve at his poverty,

for the universal kingdom has been revealed.

Let no one mourn that he has fallen again and again;

for forgiveness has risen from the grave.

Let no one fear death, for the Death of our Savior has set us free.

He has destroyed it by enduring it.

He destroyed Hell when He descended into it.

He put it into an uproar even as it tasted of His flesh.

Isaiah foretold this when he said,

“You, O Hell, have been troubled by encountering Him below.”

Hell was in an uproar because it was done away with.

It was in an uproar because it was mocked.

It was in an uproar, for it was destroyed.

It is in an uproar, for it is annihilated.

It is in an uproar, for it is now made captive.

Hell took a body, and discovered God.

It took earth, and encountered Heaven.

It took what it saw, and was overcome by what it did not see.

O death, where is thy sting?

O Hell, where is thy victory?

Christ is Risen, and you, O death, are annihilated!

Christ is Risen, and the evil ones are cast down!

Christ is Risen, and the angels rejoice!

Christ is Risen, and life is liberated!

Christ is Risen, and the tomb is emptied of its dead;

for Christ having risen from the dead,

is become the first-fruits of those who have fallen asleep.

To Him be Glory and Power forever and ever. Amen!

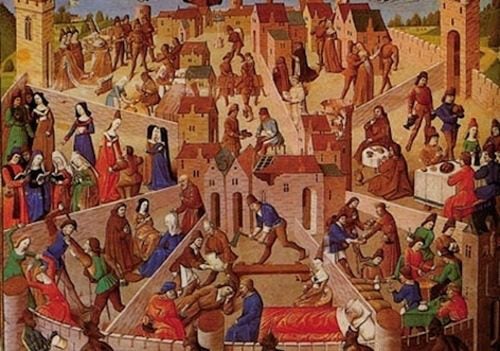

Illustration: Mosaic of St. John Chrystostom (11th century), Hosios Loukas [St. Luke’s] Monastery, Boeotia, Greece [Public domain] via Wikimedia Commons