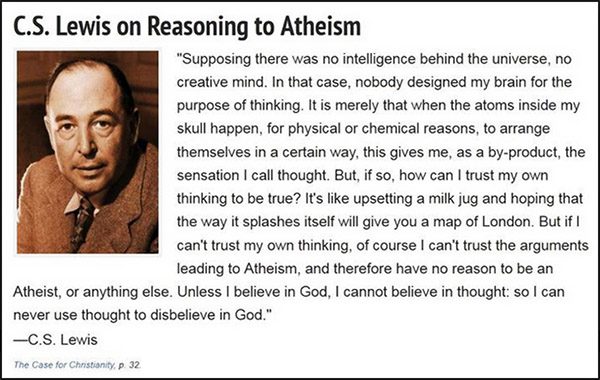

I see a quote from C.S. Lewis circulated quite a bit, and I’d like to give my response to the argument it presents. Perhaps when I am done explaining what’s wrong with it, you will start to see why Lewis admitted later in life that:

Nothing is more dangerous to one’s own faith than the work of an apologist. No doctrine of that faith seems to me so spectral, so unreal as one that I have just successfully defended in a public debate.

Indeed, I found the same thing myself. I often wonder if Lewis himself, given a bit more time, might would have eventually left his faith as well, or at least would have gravitated into the “spiritual but not religious” crowd increasingly dominating the religious landscape in the West today. But that’s none of my business.

Here is what Lewis said:

It reads:

“Supposing there was no intelligence behind the universe, no creative mind. In that case, nobody designed my brain for the purpose of thinking. It is merely that when the atoms inside my skull happen, for physical or chemical reasons, to arrange themselves in a certain way, this gives me, as a by-product, the sensation I call thought.

But, if so, how can I trust my own thinking to be true? It’s like upsetting a milk jug and hoping that the way it splashes itself will give you a map of London. But if I can’t trust my own thinking, of course I can’t trust the arguments leading to Atheism, and therefore have no reason to be an Atheist, or anything else.

Unless I believe in God, I cannot believe in thought: so I can never use thought to disbelieve in God.”

Now I see two or three major problems with this.

Let’s Run with This Analogy

Suppose you did spill a jug of milk, and suppose that somehow, inexplicably, it did produce a map of London. And not just any map of London, but a relatively accurate one—one which for the most part indicates where things are located, and one which successfully leads you to the places you desire to go. Suppose that in following this map, you arrived at your intended destination, on schedule and without much misdirection.

Would it ultimately matter that you cannot explain how the map appeared? Would that have any bearing on the usability of the map itself?

For in keeping with this analogy, that is precisely what happened with the appearance of the human mind. It matters little that this mind which invented tools and developed antibiotics and built spaceships somehow arose out of the arrangement of atoms in our skulls. The point is that however it happened, it did actually happen. Our minds exist, and they are demonstrably produced by this astoundingly complex arrangement of atoms within our skulls. Mess with the atoms, you mess with the mind.

We cannot fully explain that. Not yet, at least. But at least we know that it is what it is. And the fact that we cannot explain it does not therefore mean that any and every cockamamie story we cook up must be an accurate explanation for how it happens. That’s kind of the point of admitting we don’t know how it happens.

The fact that we cannot fully account for how it happens does nothing to invalidate the fact that our minds do exist, and they really do guide us reliably into some amazingly wonderful things. Far more than producing an accurate map of a city, these minds have envisioned and created unbelievably complex things, things which people of earlier generations would have mistaken for magic.

You could make up a delightful story about fairies pushing the milk around to produce the lines and grids that make up the map, but that wouldn’t automatically qualify as a legitimate explanation for the appearance of the map, would it? Do you see what I’m getting at? Lewis’s analogy may appear profound at first glance—at least to people already emotionally invested in agreeing with his religious beliefs. But upon further inspection it leaves a giant gulf between the phenomenon of the human mind and his facile assertion that there must be a singular thing—no, rather it has to be a person behind it all. No other explanation will do, evidently.

Arguing from Ignorance

Apparently, simply having no explanation at all, and leaving it at that, will not do for Lewis. He must supply one, even after admitting that we cannot really explain how these things work. And for some reason that explanation can only be that there is a being called God.

But hold on a second. If you can’t trust your own thinking, and if you therefore cannot trust the arguments leading to atheism, then wouldn’t it stand to reason that you similarly cannot trust the arguments that led to a belief in God? Why does the inexplicability of human cognition invalidate arguments for atheism, but not also invalidate arguments for the existence of God?

Lewis was a man of literature, and clearly not a man of science. If he had studied biology, he would have understood that the selective pressures of evolution are not completely random, even if the process of mutation is. There is an illusory appearance of intelligence produced by the forces of natural selection whereby living things develop capabilities which give them advantages over their environment. In the case of higher mammals like ourselves, we have developed advantageous cognitive abilities which, very much like that analogous map of London, have gotten us places where we want to go.

The fact that Lewis cannot explain how that can happen biologically is a very poor argument for the existence of supernatural beings. It is an argument from ignorance: “I don’t understand X, therefore God.”

Not very persuasive. Except for people who already believe. Which is why I always say that apologetics isn’t for “the lost,” it’s for the saved. It exists to assure people who already believe that they aren’t being foolish for doing so.

[Image Source: CNN]