Mercy and justice go together. Mercy makes no sense without justice, because it is through justice and its expectations we understand why various actions need to be rejected and punished, while such punishment tells us where the potential for mercy will be needed. Without mercy, without an ability to help those who have done wrong to change and be forgiven, and even helped they seek to make restitution, justice becomes legalistic and brutal, allowing no transformation, that is, it allow no possibility for someone to change for the better. Justice should be about the promotion not only of the good, but the greatest good, and the greatest good is found in the transformation of those who have done bad into those do good so that they can then add to the good found in the world. This is why pardons can make sense: if those who are being pardoned prove they have changed for the better, society would be better off welcoming them back so they can then contribute to the common good. Similarly, pardons are necessary when the punishment is excessive, that is, they help rectify the harm done by an unjust judgment. Mercy, therefore, has a role in the justice process; justice is not executed merely at the time of judgment, but all that happens afterward. William of Auvergne used the way mercy works in relation to secular justice to help us better understand God’s mercy:

Now if someone were to say that for someone who confessed to one or more crimes there is no longer any room to say something in justification of his case; rather, he should only await the sentence of condemnation, I reply that even in secular courts for those who have confessed their guilt there is room for clemency, by which the punishments are lessened, or even for forgiveness or mercy, by which someone is at times completely pardoned. For it is not possible that it is true mercy which completely does away with justice or that it is true justice which totally excludes mercy.[1]

For, as William said in one of his many prayers to God, God’s judgments and punishments are given, not to be cruel, but to help those being judged:

“Moreover, such punishments can do nothing else in those whom they are except torment and torture them, but this by itself never pleases your goodness, Lord of mercy. For you do not take delight in the perdition of the living; it is, in fact, a mark of diabolic malice, namely, to love the punishments and torments of human beings.”[2]

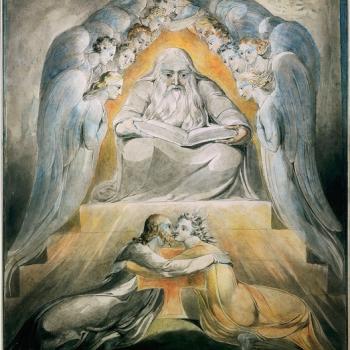

God is love, but we can also say God is justice and God is mercy. All that God does, God is. However, when examining God’s activity some actions are far more fundamental than others. We can see that behind everything God does, God’s love is found, which is why it is far more appropriate to understand God under the mantle of love than any other action. When we represent God in the world, therefore, we should take love as the foundation of our actions, doing so in a way similar to God, working, therefore, for a just mercy applied to everyone.

Love, and the mercy which comes from it, serves hope, because it shows us that God’s response to us is able to change as a result of our own personal change. We can transcend all the evil we have done, and therefore, what we have done, thanks to grace. When we transcend the evil we have done, we will be able to look back and reflect upon those evils and look at them not as something we should despair, thinking they make it impossible for us to be saved, but rather, as proof that we can become better, leaving us hope that we can continue to transcend ourselves and become all that God wants us to be. This is why Fr. George Maloney says: “Were it not for our hope that God’s eternal mercy and love will help us to transform them, it would not be a healthy thing for us to dwell on our past sins.” [3] For, if we were not offered mercy, if there were no way for us to transcend what we have currently made ourselves out to be, what we have done will only lead us to despair. We should, likewise, following the way God works with us, offer such mercy and grace to others. If we don’t do so, our own lack of mercy can adversely impact the transformation of those who need to become better, which is what Tolkien mentioned in a letter to C.S. Lewis:

What happens when the culprit is genuinely repentant, but the sufferer is deeply resentful and withholds all ‘forgiveness’? It is a terrible thought, to deter anyone from running the risk of needlessly causing such an ‘evil’. Of course, the power of mercy is only delegated and is always exercised with or without cooperation by Higher Authority. But the joys and healing of cooperation must be lost?[4]

There is a sense of this in the interplay between Samwise and Gollum in the Lord of the Rings; Sam was right to question Gollum and Gollum’s loyalty but he did so in such a way that was, for most of his time with Gollum, quite unmerciful. Sam’s lack of mercy undermined Frodo’s work with Gollum, for Frodo, with his mercy, was having a positive influence on Gollum. Nonetheless, Frodo’s mercy to Gollum helped Frodo when he needed a similar mercy, for the fact that he had failed in his mission and had begun to become like Gollum could have made it so that he would suffer the same fate of Gollum. But because of his embrace of mercy, he was able to understand mercy can be given to him, to accept it when it was offered, and not let despair destroy him (even if he would have to deal with his own failure throughout the rest of his life).

Without mercy, reformation is impossible, and so, without mercy, we often make self-fulfilling prophecies concerning those we deny mercy. But if we look to ourselves, and the way we need mercy, we should see how it is mercy which, more than anything else, which gives us not only the hope, but the ability to become better. When we offer it to others, we are offering them the chance to become better. Yes, we must exercise caution and not expect or accept instant transformation. What is important is that we should seek the kind of justice which is rehabilative and not punitive, for by doing so, we seek the greatest good, the kind which justice is meant to establish in the world. This is exactly how God acts with us, and it is how God acts, then it is how we should act, for by doing so, we live out the nature God gave us, one which is meant to reflect God’s ways in the world.

[1] William of Auvergne, Rhetorica divinia, seu ars oratoria eloquentiae divinae. Trans. Roland J Teske SJ (Walpole, MA: Peeters, 2013), 63.

[2] William of Auvergne, Rhetorica divinia, seu ars oratoria eloquentiae divinae, 89 [From an example of a prayer to God in the text].

[3] George A. Maloney, SJ, Your Sins Are Forgiven: Rediscovering the Sacrament of Reconciliation (New York: Alba House, 1994), 22.

[4] J.R.R. Tolkien, The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien. Revised and Expanded Edition. Ed. Humphrey Carpenter and Christopher Tolkien (Broadway, NY: William Morrow, 2023), 182 [Letter 113 to C.S. Lewis].

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!

N.B.: While I read comments to moderate them, I rarely respond to them. If I don’t respond to your comment directly, don’t assume I am unthankful for it. I appreciate it. But I want readers to feel free to ask questions, and hopefully, dialogue with each other. I have shared what I wanted to say, though some responses will get a brief reply by me, or, if I find it interesting and something I can engage fully, as the foundation for another post. I have had many posts inspired or improved upon thanks to my readers.